CASE AUTH/2841/4/16

ANONYMOUS, NON CONTACTABLE v GLAXOSMITHKLINE GSK

Promotion of Anoro Ellipta

An anonymous, non contactable complainant complained about the promotion of long-acting beta agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LABA/ LAMA) combination inhalers for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The complainant referred to the first medicine to be licensed within this class, Ultibro Breezhaler (indacaterol maleate and glycopyrronium bromide) noting that it was clear from its European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) that the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) turned down an application that included its use to reduce COPD exacerbations, because its effects in that regard were too small to recommend such use. Ultibro Breezhaler was subsequently licensed only as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adults with COPD and thus its promotion in relation to COPD exacerbation reduction was off-label. The complainant cited other examples of what could be considered to be off-label promotion based on the CHMP ruling on LABA/LAMA combination inhaler indications and in that regard noted, inter alia, GlaxoSmithKline’s product Anoro Ellipta (vilanterol/umeclidinium) for which, according to its EPAR, a specific licence for exacerbation reduction was never applied for.

Anoro was indicated as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adult patients with COPD.

In relation to this case the complainant noted in particular that a MIMS webpage which reviewed Anoro Ellipta included the claim that COPD exacerbations were reduced by 50% compared with placebo. The complainant submitted that the item contained no information warning of the off-label aspects of the promoted use of the product.

The complainant concluded that as there was no specific indication for exacerbation reduction in the registration applications for Anoro Ellipta, the medicine was not licensed for use to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients and so promoting it to reduce COPD exacerbation reduction was off-label.

The complainant stated his/her colleagues had little awareness that LABA/LAMA combination inhalers or LAMA inhalers were being prescribed in an unlicensed manner. Also, formal recommendations for the use of these medicines in exacerbation reduction were increasingly appearing in local clinical guidelines which suggested that promotion of the medicines had not clearly communicated the off-label nature of this use. The complainant stated that the materials for the various inhalers to which he/she had drawn attention were just the tip of the iceberg; he/she knew of numerous educational meetings/symposia involving external speakers where exacerbation reduction data had been presented as part of product promotion.

A potential major concern for the complainant and his/her colleagues was that they might have unknowingly prescribed LABA/LAMA combination inhalers or LAMA inhalers to numerous COPD patients assuming that they were licensed for exacerbation reduction. The statement from the CHMP which considered exacerbation was therefore a sobering thought especially if COPD patients subsequently suffered exacerbations unexpectedly because their prescribed LABA/LAMA combination inhalers might not be effective enough as intimated by the CHMP assessment of Ultibro Breezhaler. COPD was characterised in part by airway inflammation and the extent of inflammation was progressive leading up to an exacerbation. None of the medicines in question contained an anti-inflammatory component. Another very important consideration was that prescribers were unaware from a medico-legal perspective that they would be solely liable for any adverse consequences suffered by patients which might arise.

The detailed response from GlaxoSmithKline is given below.

The Panel noted that Section 5.1 of the Anoro Ellipta summary of product characteristics (SPC) referred to its positive impact on exacerbations of COPD. The Panel noted that Section 1.1 of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline on the management of COPD listed the symptoms of the disease which were, inter alia, exertional breathlessness, chronic cough, regular sputum production and wheeze. In Section 1.3 of the Guideline, the exacerbation of COPD was described as a sustained worsening of the patient’s symptoms from their usual stable state which was beyond normal day-to-day variations and was acute in onset. In the Panel’s view, there was a difference between COPD symptoms and exacerbations of COPD although it accepted that patients whose symptoms were well controlled might be less likely to experience an exacerbation of their condition than patients with poorly controlled symptoms. In that regard the Panel considered that exacerbations might be referred to in the promotion of COPD maintenance therapy but that there was a difference between promoting a medicine for a licensed indication and promoting the benefits of treating a condition. In the Panel’s view, reference to reduced COPD exacerbation must be set within the context of the primary reason to prescribe ie maintenance therapy to relieve symptoms.

The Panel noted that Anoro Ellipta was first authorised on 8 May 2014. The MIMS article referred to by the complainant was dated 24 June 2014 and headed ‘In Depth – Anoro Ellipta: first LABA/LAMA combination inhaler for COPD’. The Panel noted GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that it did not commission the MIMS article nor did it have any editorial control over it. The company submitted that it had no awareness of its inception or publication. GlaxoSmithKline had received confirmation from the editor that MIMS articles were produced independently. The Panel considered that as the article at issue was wholly independent of GlaxoSmithKline, it did not come within the scope of the Code and no breach was ruled in that regard.

The Panel did not consider that either the primary care iPad presentation and its accompanying briefing material, nor other material, promoted Anoro Ellipta for the reduction of COPD exacerbation as alleged. Reference to exacerbations had been presented within the context of the licensed indication ie as a benefit of therapy and not the reason to prescribe per se. The Panel considered that the promotion of Anoro Ellipta had been consistent with the particulars listed in the SPC. The materials did not misleadingly imply that exacerbation reduction was a primary reason to prescribe Anoro Ellipta. Briefing materials did not present exacerbation data in such a way as to advocate a course of action which was likely to breach the Code. High standards had been maintained. No breaches of the Code were ruled.

The Panel noted that it had also been provided with copies of three certified presentations delivered by health professionals on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline. Slide 12 of a presentation entitled ‘COPD – Latest therapies’ stated that one of the aims of treatment was to reduce symptoms and increase the patient’s quality of life and also to reduce exacerbations/ admissions and mortality. Slide 36, headed ‘Exacerbations’, stated, inter alia, that Anoro produced a 50% reduction in time to first exacerbation vs tiotropium. Slide 55 clearly stated the licensed indication for Anoro ie maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adult patients with COPD. The following, and last 9 slides detailed clinical results for Anoro and gave a brief overview of the medicine. Reduction of exacerbations was not referred to on these slides. On balance, and notwithstanding one brief mention of exacerbation reduction in a set of 65 slides, the Panel did not consider that overall the presentation promoted Anoro for exacerbation reduction. No breach of the Code was ruled. The Panel, however, considered that the claim about reduced time to first exacerbation was misleading given GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that clinical studies were not designed to evaluate the effect of Anoro on COPD exacerbations. A breach of the Code was ruled.

A second presentation about breathlessness in COPD, included a number of slides specifically about Anoro including one which referred to exacerbation data from a study comparing Anoro with tiotropium. The licensed indication for Anoro was not clearly stated anywhere in the presentation. Similarly, the final presentation ‘Management and prevention of exacerbations of COPD’, gave an overview of COPD, the effects of exacerbations on patients and the role of treatment in acute exacerbation. One slide headed ‘LAMA-LABA’ stated that Anoro reduced COPD exacerbations by 50% vs placebo and also vs tiotropium. Nowhere in the presentation was the licensed indication of Anoro stated. The Panel considered that in the absence of any statement to the contrary, some viewers might assume that Anoro could be prescribed per se to reduce COPD exacerbations for which the medicine was not licensed. In that regard the Panel considered that the presentations were not consistent with the particulars listed in the SPC. A breach of the Code was ruled which was upheld on appeal by GlaxoSmithKline. The Panel considered that although Anoro exacerbation data could be referred to, it was misleading to do so when the licensed indication for the medicine had not been clearly stated and there was no statement to the effect that clinical studies were not designed to evaluate the effect of Anoro on COPD exacerbations. A breach of the Code was ruled.

With regard to the three presentations, the Panel noted its rulings of breaches of the Code above and considered that high standards had not been maintained. A further breach of the Code was ruled.

The Panel noted its rulings and comments above about the presentations but considered that the matters were not such as to bring discredit upon, or reduce confidence in, the industry. No breach of Clause 2 was ruled.

An anonymous, non contactable complainant complained about the promotion of long-acting beta agonist long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LABA/ LAMA) combination inhalers for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The complainant referred to the first medicine to be licensed within this class, Ultibro Breezhaler (indacaterol maleate and glycopyrronium bromide) and stated that although it was clear from its European Public Assessment Report (EPAR – dated 25 July 2013) that an application was originally submitted for the relief of COPD symptoms and the reduction of exacerbations, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) subsequently stated the medicine’s effects on reducing the rate of exacerbations were too small to recommend its use for such. Ultibro Breezhaler was eventually licensed as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adult patients with COPD. The complainant stated that it could be concluded that Ultibro Breezhaler was not granted a licence at the time to recommend its use for reducing exacerbations and alleged, that promotion of Ultibro Breezhaler in relation to COPD exacerbation reduction was off-label. The complainant provided a number of other examples of what could be considered to be off-label promotion based on the CHMP decision about LABA/LAMA combination inhaler indications and in relation to this case drew attention to GlaxoSmithKline’s product Anoro Ellipta (vilanterol/ umeclidinium) for which, according to its EPAR, a specific licence for exacerbation reduction was never applied for.

Anoro was indicated as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adult patients with COPD.

COMPLAINT

The complainant drew particular attention to the MIMS webpage (http://www.mims.co.uk/depth-anoro-elliptafirst-laba-lama-combination-inhaler-copd/respiratorysystem/article/1300220) which reviewed Anoro Ellipta and included the statement, ‘COPD exacerbations were reduced by 50% with vilanterol/umeclidinium compared with placebo’. The item contained no information warning of the off-label aspects of the promoted use of the product.

The complainant submitted that as there was no specific indication for exacerbation reduction in the registration applications for Anoro Ellipta, it could be concluded that the medicine was not licensed for use to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients. Therefore promotion of Anoro Ellipta in relation to COPD exacerbation reduction was off-label.

The complainant stated having spoken to his/ her peers it was evident that there was very little awareness amongst fellow colleagues that LABA/ LAMA combination inhalers or LAMA inhalers were being prescribed in an unlicensed manner. Also, formal recommendations for the use of these medicines in exacerbation reduction were increasingly appearing in local clinical guidelines which suggested that promotion of the medicines had most likely missed an ethical obligation to also clearly communicate the off-label nature of this use, either in materials or as instructions to representatives. The complainant concluded that materials for the various inhalers to which he/she had drawn attention were probably just the tip of a large iceberg. The complainant was aware of numerous educational meetings/symposia involving external speakers where exacerbation reduction data had been discussed and presented as part of product promotion.

A potential major concern for the complainant and his/her prescribing colleagues was that unknowingly, they might have prescribed LABA/LAMA combination inhalers or LAMA inhalers to numerous COPD patients based on the assumption that they were licensed for exacerbation reduction. The statement from the CHMP which considered exacerbation was therefore a sobering thought especially if treated COPD patients subsequently suffered exacerbations unexpectedly. This was because prescribing LABA/ LAMA combination inhalers might not be effective enough as intimated by the CHMP assessment of Ultibro Breezhaler. COPD was characterised in part by airway inflammation and the extent of inflammation was progressive leading up to an exacerbation. None of the medicines in question actually contained an anti-inflammatory component. Another very important consideration was that prescribers were unaware from a medico-legal perspective that they would be solely liable for any adverse consequences suffered by patients which might arise.

In writing to GlaxoSmithKline the Authority asked it to respond to Clauses 2, 3.2, 7.2, 9.1 and 15.9. The edition of the Code would be that relevant at the time the materials were used.

RESPONSE

By way of background, GlaxoSmithKline submitted that COPD was a heterogeneous disease, characterised by an irreversible airflow limitation that was usually progressive. The disease manifested in different ways in different patients, with different symptoms predominating. These symptoms could include breathlessness, cough, wheeze and sputum production. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines (Section 1.3.1) defined an exacerbation of COPD as ‘a sustained worsening of the patient’s symptoms from their usual stable state which is beyond normal day-to-day variations, and is acute in onset’. Differing symptoms, degrees of breathlessness, limitations to airflow, and risk of exacerbations gave rise to a heterogeneous patient population.

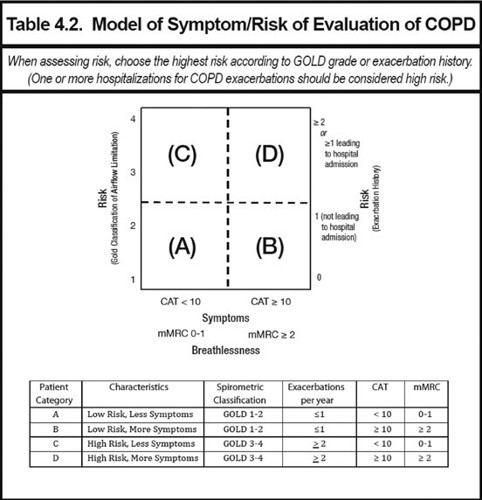

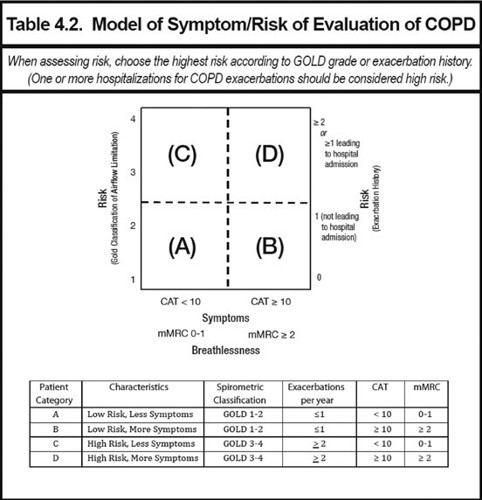

GOLD, Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2016.

This heterogeneity was reflected in widely used patient classification systems, such as that found within the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Guidelines. GOLD was an international committee of respiratory medicine experts. Using its ‘quadrant management strategy tool’ (reproduced below) patients with COPD could be divided into four groups, based on their risk of exacerbations, lung function and degree of breathlessness.

GOLD classifications were widely used to define patient populations in COPD clinical trials, due to the international understanding and applicability of those categories.

The important role which exacerbations played within COPD was highlighted by Merinopoulou et al (2016) (44,201 patients) which demonstrated that all COPD patients were at risk of exacerbations. The authors reported that patients within all four GOLD categories experienced exacerbations. The rate of exacerbations varied from 0.83 exacerbations per person-year, in GOLD A (95% CI: 0.81–0.85) to 2.51 exacerbations per person-year, in GOLD D (95% CI:2.47–2.55).

Given the range, and crossover of symptom manifestations experienced by COPD patients, it was important to capture different aspects of the disease within clinical studies as secondary endpoints. This allowed a full measure of a medicine’s pharmacodynamic properties, and applicability to the patient population to be better understood.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) provided guidance on the clinical investigation of medicines for the treatment of COPD and reflected the need to capture the heterogeneity of the disease in clinical studies:

‘Different types of drugs may be developed for COPD which may provide symptomatic relief through improvement of airway obstruction, which may modify or prevent exacerbations or which may modify the course of the disease or modify disease progression .... Depending on the mechanism of action of the drug substance under evaluation, a complete characterisation of the effect of any therapy in COPD would require the inclusion of a number of different variables belonging to those domains expected to be affected by the study drug, because most treatments will produce benefits in more than one area.’

In conclusion, the heterogeneous nature of COPD meant that a number of different therapies were required; a complete characterisation of these medicines required assessment of a number of different clinical endpoints.

GlaxoSmithKline explained that Anoro Ellipta was an inhaled long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long acting beta2 agonist (LAMA/LABA) combination product, which in the EU was indicated as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adults with COPD. It had been generally available in the UK since 24 June 2014.

Anoro was a long-acting, dual bronchodilator, which primarily acted to dilate the airways and improve airflow. This helped to relieve symptoms of COPD, including breathlessness. The primary outcome of Anoro Ellipta efficacy studies were therefore measures of lung function, such as FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second). Secondary endpoints included measures of breathlessness, quality of life, use of rescue medication, exacerbations, exercise endurance and lung volume.

The EPAR for Anoro Ellipta assessed that there was a place for the use of Anoro across all COPD patients as follows:

‘Indication

As all the efficacy studies predominantly included subjects from the GOLD category B (88%) and as consequence any conclusions drawn are likely to be applicable to this subset only. However the claimed indication would allow all four GOLD categories to be treated with the combination as a first line treatment. During the evaluation the Applicant was requested to justify the indication claimed. The Applicant did clarify that the estimate of 88% of subjects falling in to Group B was based on partial data (mMRC score and exacerbations). When all relevant data (including airflow limitation) was added, 58% subjects were group D and 42% were Group B. A reasonable proportion of subjects across the grade II-IV (GOLD grading based on spirometry) was represented in the studied population. Therefore it was accepted by the CHMP that the results are likely to be relevant to the broad COPD population.’ (emphasis added)

In summary, the EPAR report concluded that the licence issued to Anoro allowed patients within all four GOLD categories, and hence the broad COPD population, to be treated with Anoro.

In line with the European Commission guidance document regarding the contents of the summary of product characteristics (SPC), Section 5.1 of the SPC should provide:

‘limited information, relevant to the prescriber, such as the main results (statistically compelling and clinically relevant) regarding pre-specified end points or clinical outcomes in the major trials...’

‘...Such information on clinical trials should be concise, clear, relevant and balanced.’

In Section 5.1 of the EU SPC, exacerbation data for Anoro obtained from Phase 3a efficacy and safety studies, was documented:

‘Anoro reduced the risk of a COPD exacerbation by 50% compared with placebo (based analysis of time to first exacerbation: Hazard Ratio (HR) 0.5, p=0.004*); by 20% compared with umeclidinium (HR 0.8, p=0.391); and by 30% compared with vilanterol (HR 0.7, p=0.121). From the three active-comparator studies, the risk of a COPD exacerbation compared with tiotropium was reduced by 50% in one study (HR 0.5, p=0.044) and was increased by 20% and 90% in two studies (HR 1.2, p=0.709 and HR 1.9, p=0.062 respectively). These studies were not specifically designed to evaluate the effect of treatments on COPD exacerbations and patients were withdrawn from the study if an exacerbation occurred. (A step-down statistical testing procedure was used in this study and this comparison was below a comparison that did not achieve statistical significance. Therefore, statistical significance on this comparison cannot be inferred).’

Exacerbations were a pre-defined secondary endpoint, captured within key phase 3 Anoro studies. This was consistent with the EMA clinical studies guidance that stated that:

‘The rate of moderate or severe exacerbations is a clinically relevant endpoint related to the associated morbidity and mortality and the usually significantly increased health-care requirement. The frequency and/or severity of exacerbations are important outcome measures that should be considered in clinical studies in COPD.’

The inclusion of exacerbation data within Section 5.1 of the Anoro Ellipta SPC was therefore justified.

In order for clinicians and other key decision makers, to make informed choices about COPD treatments, they must be able to assess details of clinically relevant endpoints of efficacy and safety studies, including exacerbation data. This was supported by guidance from NICE:

‘The choice of drug(s) should take into account the person’s symptomatic response and preference, and the drug’s potential to reduce exacerbations, its side effects and cost.’

This further supported the inclusion of exacerbation data within Section 5.1 of the Anoro Ellipta SPC. In addition, it highlighted the importance of making exacerbation data available for health professionals and other key decision makers, within the correct context, in order to help health professionals make informed choices about the most appropriate prescribing option for their patients.

GlaxoSmithKline referred to Clauses 3.2 and 7.2 of the Code and submitted given that exacerbation data was included in Section 5.1 of the Anoro Ellipta SPC, the inclusion of this data within promotional materials was not inconsistent with the particulars of the SPC, so long as the information given was not misleading. Inclusion of data, such as exacerbation rates within studies, played an important role to provide a balanced reflection of the evidence available.

GlaxoSmithKline noted that the complainant provided a single example of material, which he/ she considered was ‘off-label’ promotion. The online article in MIMS at issue, dated June 2014, was a third party publication, which GlaxoSmithKline did not commission, and over which it had no editorial control. Indeed the company had no awareness of its inception or publication.

The editorial independence of MIMS from pharmaceutical companies was clear on its website:

‘Each MIMS product monograph is compiled by our team of pharmacists based on the approved licence information. The monograph is an expert abbreviation of the full summary of product characteristics (SPC)...’

‘MIMS is not influenced by marketing information from pharmaceutical companies and all products are included at the discretion of the editorial team.

Coverage of new products and other prescribing news is decided solely by the editorial team.’

Furthermore, GlaxoSmithKline had also received confirmation from the editor of MIMS that:

‘articles in MIMS are produced entirely independently. Each story is conceived and written solely by the editorial team, based on our opinion of what is interesting and relevant to MIMS audience, and we do not inform pharmaceutical companies of articles we plan to publish or consult with them on the content.’

In these circumstances, GlaxoSmithKline was not responsible for the content of the webpage, and therefore refuted any breaches of the Code in relation to it.

Notwithstanding the above, the statement within the article, referred to by the complainant, ‘COPD exacerbations were reduced by 50% with vilanterol/ umeclidinium compared with placebo’ was factually correct, and referenced the Anoro SPC (Section 5.1).

Other than the MIMS article, no other material pertaining to GlaxoSmithKline was specifically highlighted or provided.

GlaxoSmithKline noted that the complainant stated that he/she was aware of ‘numerous educational meetings/symposia involving external speakers where exacerbation reduction data had been discussed and presented as part of product promotion’. The complainant had not provided any specifics of those meetings, and it was unclear whether he/she referred to Anoro materials in this matter. GlaxoSmithKline was thus unable to comment specifically on this matter.

The complainant also stated that ‘promotion of the above mentioned products have most likely missed an ethical obligation to also clearly communicate the offl abel nature of this use, either in materials or as instruction to sales representatives promoting the products’. The complainant had not provided any specifics of promotional or representative material, and it was unclear whether he/she referred to Anoro materials in this matter. GlaxoSmithKline was thus unable to comment specifically on this matter.

Notwithstanding the above, GlaxoSmithKline submitted that it had demonstrated that the presence of data relating to exacerbations within promotional material was acceptable, as it supported a balanced, fair, accurate and informed understanding of information relating to a medicine.

In conclusion, GlaxoSmithKline strongly believed that the promotion of Anoro was accurate, balanced, fair and objective and provided a clear overview of relevant information, in a manner that was not misleading, and could be substantiated. All data used, including exacerbation data, was in line with the marketing authorisation and not inconsistent with the SPC.

GlaxoSmithKline refuted any breach of Clauses 3.2,

7.2 and 15.9. In the absence of these breaches, the company also refuted being in breach of Cause 9.1 and Clause 2, as it had maintained high standards and had not prejudiced patient safety.

In response to a request for further information, GlaxoSmithKline identified a number of materials which referred to exacerbation data. In each instance the data was consistent with Section 5.1 of the SPC as well as appropriately contextualised for the audience and situation.

The enclosed items were divided into a number of categories, depending on their intended use and audience.

Promotional materials

Exacerbation data did not form part of Anoro Ellipta core claims and was therefore not present in core promotional campaign materials or used proactively by representatives and so only a limited number of items fell within scope, and were summarised below. Those materials supported representatives in reactive conversations with health professionals and other key decision makers, about specific Anoro data. Where exacerbation data was included, it was consistent with that found in Section 5.1 of the Anoro SPC. This material ensured that representatives were adequately briefed on questions which might arise and enabled customers to remain informed about relevant data.

Anoro Ellipta APACTs (acknowledge, probe, answer, confirm, transition) and Q&A (ref UK/ UCV/0004/14d(2)).

The position for representatives regarding exacerbation data was outlined under the question ‘Why doesn’t Anoro have exacerbation data like tiotropium?’. This was a document which was for internal use by representatives, and supported the representative in reactively answering health professionals’ questions.

The statements; ‘our Anoro Ellipta trial program was conducted in patients whose primary concern was shortness of breath (MRC ≥ 3). Patients were excluded from the trial program if they had been hospitalised with an exacerbation of COPD 12 weeks before the trials started’, and, ‘it is important to note that these studies were not specifically designed to evaluate the effect of treatments on COPD exacerbations and patients were withdrawn from the studies if an exacerbation occurred. In all studies absolute numbers of exacerbations were low’ ensured that the data was appropriately contextualised by representatives. The statement ‘No current bronchodilator licensed for the treatment of COPD has a label indication for exacerbation risk reduction’ clarified the positioning of Anoro for the representatives. Anoro was positioned to relieve symptoms in adults with COPD, in line with Section 4.1 of the SPC. This was reinforced by the Anoro core claims used in promotional campaigns.

Anoro market access document April 2016 (ref UK/UCV/0004/14z(4))

Anoro market access document April 2016 briefing document (UK/UCV/0004/14z(3)a(1)).

The Anoro market access document was provided to a health professional, or key decision maker, to support market access reviewers by providing a more detailed overview of the wider body of evidence relevant to Anoro and information about the relevant therapy area. This was carried out in view of NICE Guidelines which stated that:

‘The choice of drug(s) should take into account the person’s symptomatic response and preference, and the drug’s potential to reduce exacerbations, its side effects and cost.’

The section about exacerbations which it contained was taken directly from the Anoro SPC. Its inclusion was part of a balanced reflection of the evidence available. The statement ‘Anoro Ellipta studies were specifically designed for breathless patients (MRC ≥ 3) and were not designed to evaluate the effect of treatments on COPD exacerbations’ ensured that the reader was clear that the data did not come from exacerbation studies. It was also made clear that exacerbation rates were safety endpoints.

GlaxoSmithKline also provided a copy of the associated representative briefing document.

Maleki-Yazdi Study Clinical Summary Booklet (ref UK/UCV/0160/14(1))

Maleki-Yazdi briefing video (ref UK/UCV/0164/14b).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Maleki-Yazdi et al (2014) was a head-to-head clinical trial which compared the safety and efficacy of Anoro Ellipta with tiotropium. The data relating to exacerbation rates were found within Section 5.1 of the Anoro SPC. The ‘clinical summary booklet’ was provided to health professionals, at their request, with a reprint of the peer reviewed paper. The statement ‘this study was not specifically designed to evaluate the effect of treatments on COPD exacerbations and patients were withdrawn from the study if an exacerbation occurred’ ensured that readers were clear that this was not an exacerbation study.

The associated briefing video was for internal use only, and supported representatives by explaining and contextualising the data. It was not to be shared with health professionals and was viewed by representatives, alongside the printed materials.

Duaklir competitor card (ref UK/RESP/0302/14k(2)) Ultibro Breezhaler briefing (UK/RESP/0302/14d).

These competitor cards were for internal use by representatives only. They were not to be shared with health professionals. The information included was only discussed reactively with health professionals, in response to direct questions from them about data included in competitor materials.

Their development was in response to the use of exacerbation data in promotional campaigns for other products in the LAMA/LABA class. The exacerbation data relating to Anoro was taken directly from the Anoro SPC. The statement, ‘the Anoro Ellipta trials were not specifically designed to evaluate the effect of treatments on COPD exacerbations. In all Anoro Ellipta studies the absolute numbers of exacerbations were low’, ensured that representatives were clear that these were not exacerbation studies.

Anoro Ellipta SPC (ref UK/UCV/0041/14(3)) Anoro SPC training quiz (ref UK/RESP/0125/15).

GlaxoSmithKline explained that representatives were provided with a copy of the Anoro Ellipta SPC to provide in specific circumstances, for example with samples if requested by a health professional. They were therefore required to read the SPC, and the associated quiz contained a question on exacerbation data, to ensure that they had reviewed the material and retained the information contained. The SPC was not used as a detail aid for conversations with customers, and as evident in the material provided above, all briefing regarding exacerbation data discussions were for reactive purposes only. Promotional core claims documents

Primary Care iPad campaign (ref UK/UCV/0011/16)

Primary Care iPad campaign briefing (ref UK/UCV/0011/16a)

Secondary Care iPad campaign (ref UK/UCV/0002/16)

Secondary Care iPad campaign briefing (ref UK/UCV/0002/16a)

Anoro Leavepiece (ref UK/UCV/0077/15a(1)).

GlaxoSmithKline noted that exacerbation data did not form part of Anoro Ellipta core claims and was therefore not present in core promotional campaign materials used proactively by representatives. The company provided copies of the Anoro primary and secondary care campaigns, used by representatives in calls with health professionals, and the Anoro leavepiece, which could be left with health professionals for their reference. These materials did not refer to exacerbation data.

Medical materials

MSL medical reactive deck - Bronchodilation and its role in preventing COPD exacerbations (ref UK/ UCV/0077/14).

MEL deck – COPD: Time for a new NICE guideline? (ref UK/CPD/0006/15(4)).

The medical scientific liaison (MSL) deck was a set of powerpoint slides that MSLs could use with customers to support reactive conversations answering specific questions from the health professional. This was carried out as scientific exchange and was non-promotional.

The MEL deck was a presentation given by specialist respiratory consultants, who were employees of GlaxoSmithKline and experts in the field, to a selective audience of health professionals. Specific exacerbation data was only given on a supplementary slide, which could be shown to health professionals if they had further questions about the topic.

External speaker presentations

Ellipta Portfolio Slide Library (ref UK/RESP/0293/14(3))

Liz Sapey 4 June 2015 (ref UK/UCV/0021/15(1)) Sarah Cowdell 9 July 2015 (ref UK/UCV/0071/15) Dr Mann 24 September 2015 (ref UK/UCV/0094/15).

GlaxoSmithKline noted that the complainant broadly raised education meetings and symposia where external speakers had presented, although no GlaxoSmithKline meetings had been specified.

External speakers may elect to present pre-prepared slides produced by the company. Exacerbation data was included as a non-compulsory slide, should the speaker consider that this was relevant and important to the audience. It was made clear that ‘exacerbations as a safety endpoint were measured in both our placebo controlled and active comparator trials vs. tiotropium’ and ‘the Anoro Ellipta clinical trial programme were not specifically designed to evaluate the effect of treatments on COPD exacerbations and patients were withdrawn from the studies if an exacerbation occurred’. This ensured the audience viewed the data within the appropriate context.

At company-sponsored events, external experts in COPD might present slides that were produced independently, by the expert. GlaxoSmithKline might provide data and images, if they were specifically requested by the speaker. Other than correcting factual inaccuracies, and ensuring that the material was in line with the Code, GlaxoSmithKline stated that it did not influence the content of these presentations. The slides were certified by the company. There were three instances where external experts’ materials included exacerbation data relating to Anoro. In each instance, the data presented reflected that in Section 5.1 of the Anoro SPC. Anoro exacerbation data formed a small percentage of each presentation and was framed appropriately within wider disease and treatment discussions.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that in conclusion, of the items enclosed, only thirteen referred to Anoro exacerbation data, reflecting a small percentage of the greater than 200 items of Anoro Ellipta representative and promotional materials produced.

GlaxoSmithKline explained that when exacerbation data had been used, it had been framed in an appropriate, transparent and responsible manner, and it was made clear that the studies referred to were not exacerbation studies.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that as exacerbation data was included in Section 5.1 of the Anoro Ellipta SPC, the inclusion of this data in promotional materials was not inconsistent with the particulars of the SPC, and hence acceptable, providing that the information given was not misleading. Inclusion of data, such as exacerbation rates within studies, played an important role to provide a balanced reflection of the evidence available.

GlaxoSmithKline maintained that in order to allow clinicians and other key decision makers to make informed choices about COPD treatments, they must be able to assess details of clinically relevant endpoints of efficacy and safety studies, including exacerbation data. This was supported by NICE guidance:

‘The choice of drug(s) should take into account the person’s symptomatic response and preference, and the drug’s potential to reduce exacerbations, its side effects and cost.’

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that it was therefore appropriate to share this data within commercial and medical materials.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted that Anoro Ellipta was indicated as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adult patients with COPD. Section 5.1 of the SPC referred to its positive impact on exacerbations of COPD. The Panel noted that Section 1.1 of the NICE Guideline on the management of COPD listed the symptoms of the disease which were, inter alia, exertional breathlessness, chronic cough, regular sputum production and wheeze. In Section 1.3 of the Guideline, the exacerbation of COPD was described as a sustained worsening of the patient’s symptoms from their usual stable state which was beyond normal dayto-day variations and was acute in onset. In the Panel’s view, there was a difference between COPD symptoms and exacerbations of COPD although it accepted that patients whose symptoms were well controlled might be less likely to experience an exacerbation of their condition than patients with poorly controlled symptoms. In that regard the Panel considered that reference to exacerbations might be included in the promotion of COPD maintenance therapy but that there was a difference between promoting a medicine for a licensed indication and promoting the benefits of treating a condition. In the Panel’s view, any reference to reduced COPD exacerbation must be set within the context of the product’s licensed indication and thus the primary reason to prescribe ie maintenance therapy to relieve symptoms.

The Panel noted that GlaxoSmithKline had been asked to consider the requirements of Clauses 2, 3.2, 7.2, 9.1 and 15.9 and advised that the edition of the Code that would be relevant would be that which was in force when the materials were used. The Panel considered, however, that given the matters at issue, the relevant, substantial requirements of Clauses 2, 3.2, 7.2, 9.1 and 15.9 had not changed since the 2014 Code (the earliest Code relevant to the material at issue) and so all of the rulings below were made under the 2016 Code.

The Panel noted that Anoro Ellipta was first authorised on 8 May 2014. The MIMS article referred to by the complainant was dated 24 June 2014 and headed ‘In Depth – Anoro Ellipta: first LABA/LAMA combination inhaler for COPD’. It was stated on the MIMS website, inter alia, that each MIMS monograph was compiled by the MIMS team of pharmacists based on the approved licence information and the SPC. It was also stated that MIMS was not influenced by pharmaceutical companies; coverage of new products was decided solely by the editorial team. The Panel noted GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that it did not commission the article nor did it have any editorial control over it. The company submitted that

it had no awareness of its inception or publication. GlaxoSmithKline had received confirmation from the editor that MIMS articles were produced entirely independently. The Panel considered that as the article at issue was wholly independent of GlaxoSmithKline, it did not come within the scope of the Code and no breach was ruled in that regard.

The Panel noted GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that exacerbation data did not form part of its core claims and thus was not present in its core promotional campaign materials or used proactively by its representatives. In that regard the Panel noted that the primary care iPad presentation posed the question ‘What is important to you when prescribing a maintenance bronchodilator?’ and did not refer to exacerbations. The accompanying briefing material referred to the appropriate positioning of LAMA/LABA as initial maintenance therapy. The secondary care presentation was similar and the relevant briefing material referred to the crucial role secondary care could play in the recommendation of Anoro Ellipta in primary care as initial maintenance therapy.

The Panel noted that most of the balance of the Anoro Ellipta materials provided were designed to support representatives in reactive conversations about specific Anoro Ellipta data. These materials referred to exacerbations but such data was usually within the context of a clear statement as to the licensed indication for the medicine and always accompanied by a statement to the effect that clinical studies were not designed to evaluate the effect of treatment on COPD exacerbations and that patients were withdrawn from the study if an exacerbation occurred e.g. the Anoro Ellipta APACTs and Q&A, the market access document and the Maleki-Yazdi Study Clinical Summary document. The briefing video on the latter referred to exacerbation data from the study but noted that it was not a primary endpoint; the summary statement at the end of the video made no reference to such data. The Portfolio COPD Ellipta Slide Library for speakers clearly stated the licensed indication for Anoro Ellipta on an introductory slide; there was no reference to its use to prevent COPD exacerbations. A non-compulsory slide did discuss time to first exacerbation data and whilst it did not include Anoro’s licensed indication on the page it did indicate prominently and at the outset all of the study caveats mentioned above.

The MSL slide deck entitled ‘Bronchodilation and its role in preventing COPD exacerbations’ gave a general overview of the matter and was for reactive presentation by the GlaxoSmithKline medical team to support reactive conversations answering specific questions from a health professional. Two slides referred to Anoro and exacerbation data. One slide, entitled ‘Why has GlaxoSmithKline not characterised [Anoro’s] efficacy in patients at high risk of exacerbations?’, included the explanation that as 12 month exacerbation studies had not been performed to generate robust exacerbation data, it was not possible to confirm the magnitude of benefit of Anoro on exacerbation. Whilst there was no statement of Anoro’s licensed indication there was no evidence before the Panel that the presentation had been used other than non-promotionally in response to a specific request about exacerbation data. The complainant bore the burden of proof in that regard.

The Panel did not consider that any of the materials referred to above promoted Anoro Ellipta for the reduction of COPD exacerbation as alleged. Reference to exacerbations had been presented within the context of the licensed indication ie as a benefit of therapy and not the reason to prescribe per se. The Panel considered that the promotion of Anoro Ellipta had been consistent with the particulars listed in the SPC. No breach of Clause 3.2 was ruled. The materials did not misleadingly imply that exacerbation reduction was a primary reason to prescribe Anoro Ellipta. No breach of Clause 7.2 was ruled. The primary and secondary care iPad briefing materials and the Maleki-Yazdi briefing video did not present exacerbation data in such a way as to advocate a course of action which was likely to breach the Code. No breach of Clause 15.9 was ruled. High standards had been maintained. No breach of Clause 9.1 was ruled.

The Panel noted that it had also been provided with copies of three presentations delivered by health professionals on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline; each presentation had been certified. Slide 12 of a presentation entitled ‘COPD – Latest therapies’ (ref UK/UCV/0071/15), stated that one of the aims of treatment was to reduce symptoms and increase the patient’s quality of life and also to reduce exacerbations/admissions and mortality. Slide 36, headed ‘Exacerbations’, stated, inter alia, that Anoro produced a 50% reduction in time to first exacerbation vs tiotropium. Slide 55 clearly stated the licensed indication for Anoro ie maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adult patients with COPD. The following, and last 9 slides detailed clinical results for Anoro and gave a brief overview of the medicine. Reduction of exacerbations was not referred to on these slides. On balance, and notwithstanding one brief mention of exacerbation reduction in a set of 65 slides, the Panel did not consider that overall the presentation promoted Anoro for exacerbation reduction. No breach of Clause 3.2 was ruled. The Panel, however, considered that the claim about reduced time to first exacerbation was misleading given GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that clinical studies were not designed to evaluate the effect of Anoro on COPD exacerbations. A breach of Clause 7.2 was ruled.

A second presentation about breathlessness in COPD (ref UK/UCV/0021/15(1)), included a number of slides specifically about Anoro including one which referred to exacerbation data from a study comparing Anoro with tiotropium. The licensed indication for Anoro was not clearly stated anywhere in the presentation. Similarly, the final presentation (ref UK/UCV/0094/15)

‘Management and prevention of exacerbations of COPD’, gave an overview of COPD, the effects of exacerbations on patients and the role of treatment in acute exacerbation. One slide headed ‘LAMA-LABA’ stated that Anoro reduced COPD exacerbations by 50% vs placebo and also vs tiotropium. Nowhere in the presentation was the licensed indication of Anoro stated. The Panel considered that in the absence of any statement to the contrary, some viewers might assume that Anoro could be prescribed per se to reduce COPD exacerbations for which the medicine was not licensed. In that regard the Panel considered that the presentations were not consistent with the particulars listed in the SPC. A breach of Clause 3.2 was ruled. This ruling was appealed by GlaxoSmithKline. The Panel considered that although Anoro exacerbation data could be referred to, it was misleading to do so when the licensed indication for the medicine had not been clearly stated and there was no statement to the effect that clinical studies were not designed to evaluate the effect of Anoro on COPD exacerbations. A breach of Clause 7.2 was ruled.

With regard to the three presentations, the Panel noted its rulings of breaches of the Code above and considered that high standards had not been maintained. A breach of Clause 9.1 was ruled.

The Panel noted that a ruling of a breach of Clause 2 was a sign of particular censure and reserved for such. The Panel noted its rulings and comments above about the presentations but considered that the matters were not such as to bring discredit upon, or reduce confidence in, the industry. No breach of Clause 2 was ruled.

APPEAL BY GLAXOSMITHKLINE

GlaxoSmithKline appealed the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 3.2 with regard to the two presentations (refs UK/UCV/0021/15(1) and UK/ UCV/0094/15).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the complainant’s most pertinent concern was that ‘Anoro Ellipta ... (is) not licensed for use to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients ... therefore promotion of Anoro Ellipta in relation to COPD exacerbation reduction is off-label’.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the use of Anoro Ellipta for the treatment goal of reducing the patient’s risk of suffering a COPD exacerbation was not ‘off-label’, and was consistent with the licensed therapeutic indication (Section 4.1 of the SPC); it was also in line with national and international guidelines for the treatment of COPD, and was consistent with the manner by which patients with COPD, a heterogeneous disease, were managed by clinicians.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Section 4.1 of the Anoro Ellipta SPC, stated that:

‘Anoro is indicated as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adult patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).’

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that this was the product’s licence and guided a clinician to prescribe ‘within label’.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that symptoms and ‘exacerbations’ fell along a continuum in COPD. There was no diagnostic test or biomarker to define an ‘exacerbation’ of COPD. Widely accepted definitions of ‘exacerbations’ recognised this and referred to a worsening of symptoms from a baseline of normal day-to-day variations, along this continuum, to an arbitrary threshold level. The modified Anthonisen criteria, a widely used definition for exacerbations in clinical trials, required an increase in symptoms for only two days.

‘Respiratory symptoms were classified as “major” symptoms (dyspnea, sputum purulence, sputum amount) or “minor” symptoms (wheeze, sore throat, cough, and symptoms of a common cold which were nasal congestion/discharge). Exacerbations were defined as the presence for at least two consecutive days of increase in any two “major” symptoms or increase in one “major” and one “minor” symptom according to criteria modified from Anthonisen and colleagues.’ (Seemungal et al 2000).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society task force definition provided further clarification as to the continuum of worsening COPD symptoms and stratified exacerbation severity by the level of treatment which was required.

‘- mild, which involves an increase in respiratory symptoms that can be controlled by the patient with an increase in the usual medication;

moderate, which requires treatment with systemic steroids and/or antibiotics; and

severe, which describes exacerbations that require hospitalisation or a visit to the emergency department’ (Cazzola et al 2008).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that national and international guidelines also acknowledge that the definition of an exacerbation of COPD was based on symptoms, and given the variability in the clinical presentation of individual patients, the definition consistently referenced the patient’s baseline level of symptoms.

‘An exacerbation of COPD is an acute event characterized by a worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-today variations and leads to a change in medication’ (GOLD, Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2016).

‘An exacerbation is a sustained worsening of the patient’s symptoms from their usual stable state which is beyond normal day-to-day variations, and is acute in onset. Commonly reported symptoms are worsening breathlessness, cough, increased sputum production and change in sputum colour. The change in these symptoms often necessitates a change in medication’ (NICE, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management, 2010).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that studies also showed that symptom burden and exacerbations were intrinsically linked. In a survey of 2531 patients with COPD the correlation between breathlessness and exacerbations was assessed. It was found that patients with a higher burden of breathlessness experienced more frequent exacerbations (Punekar et al 2016).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that if a patient’s symptoms were relieved by Anoro Ellipta, then a sustained worsening in these symptoms was less likely and would be less severe, hence reducing the risk and severity of an exacerbation. Given that exacerbations and symptoms were intrinsically linked, it could not be stated that treating symptoms did not help prevent future exacerbations.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that it was also important to recognise the heterogeneous nature of COPD. The majority of diagnosed COPD patients suffered from symptoms, which included breathlessness, cough, wheeze and sputum production. All patients were also at risk of suffering exacerbations, however the level of risk was different for different patients – this was distinctly different from a condition where some subgroups of patients had an exacerbating type of the disease, whilst others had a non-exacerbating type of the disease. GlaxoSmithKline submitted that this principle of COPD was clearly captured by the quadrant management strategy tool in the GOLD Guideline and reproduced above. The grid nature of this recognised that patients might have varying levels of symptom burden and risk, and that the combination of these which existed, helped determine which treatment class needed to be used.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the treatment options stipulated for categories A, B, C and D, recognised that all patients needed to be treated for their symptom burden and to reduce their risk of future exacerbations, however the specific class of medicine chosen changed depending on the level of symptoms and exacerbation risk.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that GOLD Guideline supported the use of long-acting bronchodilators to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients.

‘Both long-acting anticholinergic and long-acting beta2-agonist reduce the risk of exacerbations.’

‘COPD exacerbations can often be prevented.... treatment with long-acting inhaled bronchodilators, with or without inhaled corticosteroids... are all interventions that reduce the number of exacerbations and hospitalizations.’ (GOLD, Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2016).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that due to this, the LAMA/LABA class was listed as a treatment choice for patients in GOLD groups B, C and D.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the Anoro EPAR concluded that there was a place for the medicine in treating patients across the continuum of all severities of disease, and in all GOLD groups.

‘The claimed indication would allow all four GOLD categories to be treated with the combination as a first line treatment... it was accepted by the CHMP that the results are likely to be relevant to the broad COPD population’ (EMA, European Public Assessment Report 2014).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the Anoro EPAR clarified that as 42% of subjects in Anoro clinical trials were in GOLD group B, and 58% were in GOLD group D, the licence granted allowed for all four GOLD categories to be treated with Anoro Ellipta as a first line treatment. A key difference between patients in GOLD B and D was an increase in exacerbation risk, and hence the EPAR confirmed that patients with an exacerbation risk could be prescribed Anoro.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that NICE Guidelines also recognised that both symptoms (breathlessness) and reducing exacerbation risk were key treatment goals in managing COPD. As such, those suffering from either need to progress from short-acting therapy to long-acting maintenance therapy, which included bronchodilators (LAMA, LABA or LAMA + LABA).

GlaxoSmithKline noted that none of the COPD treatments licensed in the UK were indicated to reduce exacerbations. This included the licences of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)/LABAs, which were widely recognised as the most established inhaled therapy class for exacerbation reduction in COPD patients.

GOLD Guidelines clearly stated that inhaled corticosteroids reduced exacerbations and positioned the ICS/LABA class as a first line treatment for patients with a high risk of exacerbations:

‘Regular treatment with inhaled corticosteroids improves symptoms, lung function, and quality of life, and reduces the frequency of exacerbations in COPD patients with an FEV1 < 60% predicted.’

‘Long-term treatment with inhaled corticosteroids added to long-acting bronchodilators is recommended for patients at high risk of exacerbations...Group C patients have few symptoms but a high risk of exacerbations. As first choice a fixed combination of inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta2-agonist or a longacting anticholinergic is recommended.’ (GOLD, Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2016).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that this was in line with NICE Guidelines, which positioned ICS/LABAs as a recommended long-acting therapy for patients with airflow restriction who had exacerbations or persistent breathlessness, or in any COPD patient who remained breathless or had exacerbations despite long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that all ICS/LABAs had similar wording within their licences, and for simplicity it referred to the Seretide licence as the benchmark for this class. The rationale being that this was the first product licensed in this class, and it remained the product with largest market share in the class. Section 4.1 of the Seretide Accuhaler SPC stated:

‘Seretide is indicated for the symptomatic treatment of patients with COPD, with a FEV1 <60% predicted normal (pre-bronchodilator) and a history of repeated exacerbations, who have significant symptoms despite regular bronchodilator therapy.’ (emphasis added).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that it was clear that the licence for Seretide was for the treatment of symptoms of COPD. Given the recommended position of ICS/LABAs within guidelines, and the widespread use and promotion of this class for exacerbation reduction, the precedent was that an indication for the treatment of symptoms of COPD encompassed use for reducing exacerbation risk.

Notwithstanding the above, GlaxoSmithKline acknowledged that the exacerbation data from Section 5.1 of the Anoro SPC must be presented in a manner which did not mislead. It should be clear that this data was not a primary endpoint in the studies presented, and relevant detail should be provided on the population studied, e.g. low risk of exacerbations. It should also be clear what the full licensed indication for Anoro was, such that readers could contextualise the data within the broader licensed indication. Therefore GlaxoSmithKline accepted the breaches of Clauses 7.2 and 9.1.

In conclusion, GlaxoSmithKline strongly maintained that the use of Anoro Ellipta in COPD to improve symptom burden and reduce the risk of future exacerbations was not outside of the scope of the product indication. Such practice was also in line with national and international guidelines which reflected the way COPD patients were managed by health professionals. As such, GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the presentations in question did not breach Clause 3.2.

APPEAL BOARD RULING

The Appeal Board noted that that Anoro Ellipta was indicated as a maintenance bronchodilator treatment to relieve symptoms in adults with COPD. Although information regarding a reduced risk of COPD exacerbation was stated in Section 5.1 of the SPC, promoting any reduction in such risk had to be set within the context of using the medicine for its licensed indication. In particular, the Appeal Board noted GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that including the exacerbation data in promotional materials was not inconsistent with the SPC provided that the information given was not misleading. GlaxoSmithKline had accepted the Panel’s rulings that the two presentations were misleading.

The Appeal Board noted that neither presentation at issue contained a clear statement as to the licensed indication for Anoro Ellipta. In the Appeal Board’s view, to present exacerbation data without that context invited the audience to assume that Anoro Ellipta could be used to reduce COPD exacerbation per se, for which the medicine was not licensed. The Appeal Board thus considered that the presentations were inconsistent with the Anoro Ellipta SPC and it upheld the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 3.2. The appeal on this point was not successful.

Complaint received 22 April 2016

Case completed 3 November 2016