CASES AUTH/2825/3/16 and AUTH/2826/3/16 JANSSEN v BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM and LILLY

Promotion of Jardiance

Janssen-Cilag complained about a Jardiance (empagliflozin) letter distributed by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly and Company (the Alliance) representatives which was stapled to a copy of Zinman et al (2015), (the EMPA-REG study) and a one sided A4 sheet of prescribing information. The letter referred to cardiovascular outcome data.

Janssen explained that Jardiance was a sodium glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor indicated to improve glycaemic control in type 2 diabetic adults either as monotherapy or combination therapy. The only reference to any cardiovascular outcomes in the Jardiance summary of product characteristics (SPC) was in Section 5.1 as follows:

‘Cardiovascular safety

In a prospective, pre-specified meta-analysis of independently adjudicated cardiovascular events from 12 phase 2 and 3 clinical studies involving 10,036 patients with type 2 diabetes, empagliflozin did not increase cardiovascular risk.’

Janssen stated that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandated that all new glucose-lowering agents should include a metaanalysis of the cardiovascular safety outcome studies to be carried out by the market authorization holder on new molecules licensed after July 2008, to demonstrate that the therapy would not result in an unacceptable increase in cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Hence the above SPC wording. In addition, the Alliance initiated The EMPA-REG study which was listed in the risk management plan for Jardiance.

Zinman et al (2014) and Zinman et al (2015) described in detail the rationale, design and baseline characteristics of the EMPA-REG study together with the following caveat regarding the results:

‘The results may not be generalizable (e.g., to patients with type 2 diabetes without cardiovascular disease), the risk–benefit profile for this drug class will need further elucidation (particularly for adverse events), and the ultimate position of empagliflozin among multiple drugs in the clinical management of type 2 diabetes will still need to be defined. Thus, it will be important to confirm these results with findings from other ongoing trials of SGLT2 inhibitors’

(Ingelfinger and Rosen 2016).’

In view of the EMPA-REG study results the Alliance applied for a new indication for the prevention of cardiovascular events to be included in Section 4.1 of the Jardiance SPC. No decision had been made by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) as yet.

Janssen noted that the letter at issue, dated January 2016, was designed to inform health professionals about the results of the EMPA-REG study. A large part of the letter described the cardiovascular risk reduction seen with Jardiance. By proactively disseminating this letter, via its sales force, the Alliance had promoted the use of Jardiance to reduce cardiovascular risk ahead of an approval of the licensed indication. Although a statement ‘Jardiance is not indicated for the treatment of weight loss, blood pressure control or cardiovascular risk reduction’ was in the section describing the posology of Jardiance, this restriction was not clear from the outset as it appeared on page 2 of the letter and was not prominently displayed.

Janssen also alleged that the promotional letter closely, and inappropriately, resembled a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter, which was reserved for special communication to health professionals of important events such as safety alerts, and so was misleading in this regard. Moreover, the letter was signed by senior medical employees of the Alliance who held overall responsibility for compliance with the Code.

A number of breaches of the Code were alleged.

The detailed response from the Alliance is given below.

The Panel noted that page 1 of the letter bore no company name, logo or address and no prominent name or logo of a medicine. The envelope was plain. It was not immediately obvious who the letter was from or what it was about. In that regard the Panel noted that the material had been handed out to a health professional after a 1:1 Jardiance call with an Alliance representative and whilst the recipient would have had the benefit of that interaction, anyone else picking up the material might not realise where it had come from. The briefing material regarding the use of the material (dated 12 January 2016) stated that the EMPAREG study represented a significant milestone in the treatment of diabetes but that the company was unable to discuss it in detail until the relevant authorization and training was provided. With regard to ‘the relevant authorization’, the Panel noted that the CHMP agenda for its February 2016 meeting showed that an application for a licence extension for Jardiance to include prevention of cardiovascular events based on the EMPA-REG study results had been submitted. The briefing material stated that the EMPA-REG study should only be given out until 30 June 2016 but without any discussion other than the following mandatory verbatim:

‘You may be aware of the regulatory requirement to conduct cardiovascular outcome studies for all new antidiabetic agents. The cardiovascular outcome study for Jardiance was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in September 2015.

In this folder you will find a reprint of the paper. The study forms part of a potential SPC update and I am unable to discuss it further with you. However, the folder includes an accompanying letter from our Medical Directors which indicates how further information may be obtained together with Jardiance prescribing information.’

The letter was addressed ‘Dear UK Healthcare Professional’. The second of the first two very short introductory paragraphs stated that Jardiance was a glucose-lowering agent for the treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes; it was not stated, as in the SPC, that it was indicated solely to improve glycaemic control. The most prominent section on page 1 was headed ‘Recent Cardiovascular Outcomes Data’ and took up the rest (approximately 75%) of the page. In that regard the Panel noted that, due to concerns that glucoselowering medicines might be associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes (type 2 diabetes was itself a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease), the EMPA-REG study was a cardiovascular safety study mandated by the regulators; it was designed to address long-term (median 3.1 years) safety concerns, not to generate efficacy data for a possible new indication. Four bullet points detailed the main results from Zinman et al (2015) including that Jardiance significantly reduced the relative risk of the combined primary endpoint, of cardiovascular death, non-fatal heart attack or non-fatal stroke by 14% vs placebo. This was in contrast to the Jardiance SPC which stated that Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk. Page

2 of the letter stated the licensed indication for Jardiance (to improve glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes) and that the medicine was not indicated for, inter alia, cardiovascular risk reduction. It was further stated that if the reader had any questions or would like to discuss the EMPA-REG study with an Alliance medical advisor, this could be arranged by contacting the medical information department. The letter appeared to have been jointly sent from a medical director from each company.

In the Panel’s view it was clear from the briefing given to the representatives that Zinman et al (2015) would form the basis of a proposed change to the SPC and in that regard representatives were instructed not to proactively or reactively discuss the study. By proactively distributing the material at issue, however, the Alliance was knowingly using its representatives to solicit queries about the study, the results of which it knew were inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC. The Panel noted that although the Code did not prevent the legitimate exchange of medical and scientific information during the development of a medicine, provided that such information or activity did not constitute promotion, representatives distributing the material at issue after a 1:1 Jardiance call, clearly constituted the promotion of Jardiance.

The Panel considered that the prominence given within the letter to the cardiovascular outcome data from the EMPA-REG study promoted Jardiance for cardiovascular risk reduction for which it was not licensed. The results of the study went beyond the SPC statement that Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk. The results were not presented in the context of the safety profile for Jardiance. The statement on page 2 that Jardiance was not indicated for cardiovascular risk reduction was insufficient to mitigate the otherwise misleading and primary impression given by page 1 and the reference to outcomes data. In the Panel’s view, the material was preparing the market for an anticipated licence extension. A breach of the Code was ruled which was upheld on appeal.

The Panel noted the allegation that the letter resembled a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter and was therefore disguised promotion. The Panel assumed that the ‘Dear Doctor’ letters referred to were those sent by companies to convey important product safety information at the request of the MHRA. The Panel considered that given the very bland and not obviously promotional appearance of the letter, some recipients might assume that it was important safety information, or other nonpromotional information, even if it had been handed to them by a representative. In the Panel’s view, not all recipients would be so familiar with ‘Dear Doctor’ letters such that they would immediately recognise any difference. In the Panel’s view the representatives’ mandatory verbatim was not sufficiently clear about the status of the material; in any event the letter should be able to stand alone with regard to compliance with the Code. In the Panel’s view, despite the material being distributed by representatives, its promotional intent was not immediately obvious and in that regard it was disguised. A breach of the Code was ruled which was upheld on appeal.

The Panel noted that the Code required companies to appoint a senior employee to be responsible for ensuring that the company met the requirements of the Code. The Alliance met these requirements and so no breach of the Code was ruled.

The Panel considered that high standards had not been maintained. A breach of the Code was ruled which was upheld on appeal. The Panel was further concerned that the Alliance appeared to have knowingly distributed material which was inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC and which it would use to support a licence extension for a currently unlicensed indication. A breach of Clause 2, a sign of particular censure, was ruled and upheld on appeal.

The Panel noted its reasons for ruling breaches of the Code as set out above. In addition, the Panel was extremely concerned that the Alliance had given its representatives material to distribute to health professionals which it knew they could not discuss with those health professionals. In the Panel’s view this gave a wholly inappropriate signal to the representatives regarding compliance and was completely unacceptable; it compromised the representatives’ position and demonstrated a very poor understanding of the Code on behalf of the signatories. In that regard, and in accordance with Paragraph 8.2 of the Constitution and Procedure, the

Panel decided to report the Alliance to the Appeal Board for it to consider whether further sanctions were appropriate.

The Appeal Board noted its comments and rulings of breaches of the Code including a breach of Clause 2. The Appeal Board considered that the Alliance’s actions either showed a disregard for, or a fundamental lack of understanding of, the requirements of the Code. The amount of time the companies had spent discussing the position before issuing the letter implied they were aware of the risks involved. The Appeal Board did not accept, as submitted by the Alliance, that the issues in this case were due to a grey area of the Code. It appeared that the Alliance had decided to put commercial gain before compliance. This was totally unacceptable.

The Appeal Board was very concerned that health professionals had been provided with material which promoted Jardiance for an unlicensed indication. This was unacceptable. Consequently, the Appeal Board decided, in accordance with Paragraph 11.3 of the Constitution and Procedure, to require the Alliance to issue a corrective statement to all recipients and to take steps to recover the material. (The corrective statement, which was agreed by the Appeal Board prior to use, appears at the end of this report).

The Appeal Board also decided that, given its concerns set out above, to require, in accordance with Paragraph 11.3, an audit of both Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim’s procedures in relation to the Code with an emphasis on the activities of the Alliance. The audits would take place as soon as possible. On receipt of the audit reports, the Appeal Board would consider whether further sanctions were necessary.

Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly were audited in July 2016 and the audit reports were considered by the Appeal Board in September.

The Appeal Board noted from both audit reports concerns about the governance of the Alliance although it was pleased to note a greater involvement of the compliance function on the senior governance committee.

The Appeal Board noted from the Boehringer Ingelheim audit report that, inter alia, there were concerns about the company’s standard operating procedures (SOPs), staff training and control of advisory boards. The Appeal Board considered that staff throughout the company needed to urgently improve and demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the Code and commitment to compliance.

The Appeal Board noted that Boehringer Ingelheim had completed some of the work on its compliance action plan but it still had much to do. The Appeal Board noted its comments above and considered that Boehringer Ingelheim should be re-audited in March 2017 when it would expect the company’s action plan to be complete and the company able to demonstrate considerable improvement in compliance culture and process.

The Appeal Board noted from the Lilly audit report that compliance and ethics were highly valued at the company and its staff had understood and genuinely regretted the failings in this case. However, the audit report highlighted concerns about the company’s SOPs, its approval process and governance of advisory boards.

The Appeal Board noted that some work on Lilly’s compliance plan was already complete and that all actions were due to be completed by the end of October 2016. The Appeal Board considered that Lilly should be re-audited around the same time as Boehringer Ingelheim. On receipt of the report for the March 2017 re-audit in relation to Boehringer Ingelheim and the company’s response to subsequent questions raised by the Appeal Board, the Appeal Board decided that no further action was required.

On receipt of the report for the March 2017 re-audit in relation to Lilly and the company’s responses to subsequent questions raised by the Authority and points raised by a whistleblower the Appeal Board decided that, on balance, no further action was required.

Janssen-Cilag complained about a Jardiance (empagliflozin) ‘Dear UK Healthcare Professional’ covering letter (ref UK/EMP/00241) distributed by Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd and Eli Lilly and Company Ltd (the Alliance) representatives. The two sided, A4 letter was stapled to a copy of Zinman et al (2015), ‘Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes’ (the EMPA-REG study) and a one sided A4 sheet which gave the prescribing information for Jardiance. The three items were stapled together and put in an envelope to be given to health professionals after a 1:1 call by representatives.

Jardiance was indicated in the treatment of type 2 diabetes to improve glycaemic control in adults: as monotherapy when diet and exercise alone did not provide adequate glycaemic control in patients for whom use of metformin was considered inappropriate due to intolerance and in combination with other glucose-lowering medicinal products including insulin, when these, together with diet and exercise, did not provide adequate glycaemic control.

COMPLAINT

Janssen noted the licensed indication for Jardiance (a sodium glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor) and provided a copy of the summary of product characteristics (SPC). The only reference to any cardiovascular outcomes in the SPC was in Section 5.1 as follows:

‘Cardiovascular safety

In a prospective, pre-specified meta-analysis of independently adjudicated cardiovascular events from 12 phase 2 and 3 clinical studies involving 10,036 patients with type 2 diabetes, empagliflozin did not increase cardiovascular risk.’

Janssen stated that in 2008 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandated that all new glucose lowering agents should include a meta-analysis of the cardiovascular safety outcome studies to be carried out by the market authorization holder on new molecules licensed after July 2008, to demonstrate that the therapy would not result in an unacceptable increase in cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Hence the above wording in Section 5.1 of the Jardiance SPC. In addition, the Alliance initiated The EMPA-REG study which was listed in the risk management plan for Jardiance.

The primary composite outcome of the study was ‘… death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or non-fatal stroke, as analysed in the pooled empagliflozin group versus the placebo group’. The study recruited a specifically selected group of diabetics as the entry criteria mandated that all patients had to have established cardiovascular disease. During the course of the study, investigators were encouraged to adjust glucose-lowering therapy at their discretion to achieve glycaemic control according to local guidelines after the first 12 weeks. HbA1c reduction was not a primary endpoint of the study, the gold standard marker for blood glucose-lowering in type 2 diabetes clinical trials.

Full details regarding the study were in the paper ‘Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of a randomized, placebo-controlled cardiovascular outcome trial of empagliflozin (EMPA-REG OUTCOME)’ (Zinman et al 2014) and in Zinman et al (2015) together with the following caveat regarding the results:

‘The results may not be generalizable (e.g., to patients with type 2 diabetes without cardiovascular disease), the risk–benefit profile for this drug class will need further elucidation (particularly for adverse events), and the ultimate position of empagliflozin among multiple drugs in the clinical management of type 2 diabetes will still need to be defined. Thus, it will be important to confirm these results with findings from other ongoing trials of SGLT2 inhibitors’ (Ingelfinger and Rosen 2016).

In view of the EMPA-REG study results the Alliance applied for a new indication of the prevention of cardiovascular events to be included in Section 4.1 of the Jardiance SPC. This was reviewed by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) and shown on its agenda of 22 February, 2016. No decision had been made by the CHMP as yet.

Janssen noted that the covering letter at issue, dated January 2016, was designed to inform health professionals about the results of the EMPA-REG study. A large part of the letter described the cardiovascular risk reduction that had been seen with Jardiance. Janssen submitted that by proactively disseminating this letter, via its sales force, the Alliance had promoted the use of Jardiance to reduce cardiovascular risk ahead of an approval of the licensed indication. Although a statement ‘Jardiance is not indicated for the treatment of weight loss, blood pressure control or cardiovascular risk reduction’ was in the section which described the posology of Jardiance, this restriction was not clear from the outset as it appeared on page 2 of the letter and was not prominently displayed.

Janssen also alleged that the letter closely resembled a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter, which was reserved for special communication to health professionals of important events such as safety alerts, and so was misleading in this regard. This promotional letter had inappropriately used a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter style and format. Moreover it was approved and signed by the medical directors of both companies who held overall responsibility for compliance with the Code.

Janssen therefore alleged that the covering letter was in breach of the Code as it: promoted Jardiance for an unlicensed indication prior to the grant of a marketing authorization (breach of Clauses 3.2 and 2); misused a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter as promotional material and was therefore disguised promotion signed by senior members of both companies (breach of Clauses 1.12, 9.1 and 12.1) and represented failure of the senior employees within Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly to ensure the companies met the requirement of the Code (breach of Clauses 1.12 and 2).

Janssen further noted its allegations of breaches of the Code and its concern that the covering letter might be being used in other European countries given the European accountabilities of the Lilly personnel involved in the inter-company dialogue.

RESPONSE

The Alliance submitted that Jardiance was granted its marketing authorization in 2014 and was indicated for glucose control in adults with type 2 diabetes. The current wording in Section 4.1 of the SPC read:

‘Jardiance is indicated in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus to improve glycaemic control in adults as:

When diet and exercise alone do not provide adequate glycaemic control in patients for whom use of metformin is considered inappropriate due to intolerance.

- Add-on combination therapy

In combination with other glucose-lowering medicinal products including insulin, when these, together with diet and exercise, do not provide adequate glycaemic control (see Sections 4.4, 4.5 and 5.1 for available data on different combinations).’

The marketing authorization was granted on the basis of a comprehensive clinical development programme that included HbA1c as the primary endpoint in the clinical trials and weight and blood pressure as secondary/exploratory endpoints. All promotional material carried that explanatory information and that Jardiance was not indicated for weight loss or blood pressure control.

For new glucose-lowering agents, pharmaceutical companies were mandated by the regulators (European Medicines Agency (EMA) and FDA) to conduct dedicated cardiovascular outcome safety studies. There had been several of these studies reported to date for two other classes of oral anti hyperglycaemic medicines and EMPA-REG study was the first cardiovascular outcome study to report for the SGLT2 inhibitor class.

The Alliance stated that Zinman et al (2015), the EMPA-REG study, was disclosed at the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) in September 2015 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in November 2015. The study population was limited to adults with type 2 diabetes who had a history of stroke, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction or peripheral vascular disease as per the EMA guidance. Patients were not at glycaemic goal on existing therapy.

The primary endpoint was a composite cardiovascular endpoint, of cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction and non-fatal stroke. HbA1c was measured as part of the efficacy parameters of the study. The results of the study confirmed non-inferiority, but, in addition, a 14% reduction in the composite endpoint was observed driven by a 38% reduction in cardiovascular death. This was over a median follow-up period of just over 3 years. In addition, there was a 32% reduction in all-cause mortality and a 35% reduction in hospitalisation for heart failure.

The covering letter at issue led with an introduction to Zinman et al (2015) and the indication for Jardiance followed by a synopsis of the study including safety data relating to cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular events. New and relevant data about the use of Jardiance as a glucose-lowering agent and the impact it had on cardiovascular outcomes was included in the letter and was balanced with the appropriate caveats about the composition of the study population that were relevant to the restrictions of the Jardiance SPC.

The Alliance submitted that the EMPA-REG study was conducted in adults with type 2 diabetes as per the SPC. The endpoints and data collected were consistent with the SPC which specifically mentioned cardiovascular outcomes within Section 5.1 and HbA1c as a recognised biomarker for diabetes control. Data from EMPA-REG study had been submitted to the EMA for inclusion within Sections 4.1 and 5.1 of the Jardiance SPC. However, the proposed amendments would not change the target disease, method of treatment or enlarge the eligible patient population for treatment with Jardiance. The overall design of the study was consistent with the Jardiance SPC and the data presented in the study did not enlarge the target disease, target population or method of treatment of type 2 diabetes with Jardiance. The Alliance noted that the covering letter referred to the current indication regarding glycaemic control and clearly stated that Jardiance was currently not indicated for cardiovascular risk reduction.

The Alliance stated that the covering letter together with a copy of Zinman et al (2015) and the Jardiance prescribing information (ref EMP/UK/00241) were distributed by the field force in accordance with the Code with an associated briefing document (ref EMP/ UK/00240) (copy provided). The MHRA had provided clear guidance on the drafting of ‘Dear Doctor’ letters including a template. From this template it was clear that the letter at issue did not resemble a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter. Furthermore, the letter included prescribing information and was disseminated by the field force at the end of a call and within a clear folder. The letter did not therefore resemble a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter in appearance and the way in which it was distributed by the sales force also made it clear that it was not a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter. The letter and activity by the Alliance was certified in January 2016.

The Alliance denied that its activities were in breach of the Code.

The Alliance denied a breach of Clause 1.12. The dissemination of the letter was a promotional activity and certified accordingly. Responsible senior employees were appointed to ensure the Alliance met the requirements of the Code.

The Alliance did not consider the activity breached Clause 3.2 which stated that promotion ‘…must be in accordance with the terms of its marketing authorization and must not be inconsistent with the particulars listed in its summary of product characteristics’. Further, the supplementary information to Clause 3.2 stated that ‘the promotion of indications not covered by the marketing authorization is prohibited by this clause’. The Alliance considered that this allowed for new and important data to be disseminated in a promotional capacity if the data was not inconsistent with the SPC, and no indication was promoted which was not covered by the marketing authorization.

Janssen appeared to criticise the fact that HbA1c reduction was not a primary outcome of the EMPAREG study, but the Alliance noted that HbA1c was a surrogate marker of diabetes control, whereas the EMPA-REG study had measured and reported hard clinical endpoints associated with diabetes namely all-cause mortality, cardiovascular heart and hospitalisations due to heart failure.

Type 2 diabetics had an increased risk for cardiovascular events and Section 5.1 of the Jardiance SPC referred to a meta-analysis of independently adjudicated cardiovascular events from phase 2 and 3 clinical trials. In this metaanalysis, Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk. This was an analysis performed as part of the European Public Assessment Report (EPAR). Importantly, the results from the EMPA-REG study, in referring to cardiovascular outcomes in the context of treating adult type 2 diabetics, were thus consistent with the current SPC that Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk.

The covering letter was also clear that Jardiance was not indicated for cardiovascular benefit; Jardiance was presented as a glucose-lowering agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and the letter simply shared new and relevant clinical trial data that was consistent with the SPC.

The marketing authorization for Jardiance stated that it was authorised for use as a glucose-lowering agent. The letter at issue clearly stipulated the indication of Jardiance in its context as a glucoselowering agent and stated ‘Jardiance is not indicated for the treatment of weight loss, blood pressure control or cardiovascular risk reduction’. It did not state that Jardiance should be used for any patients other than adult, type 2 diabetics.

With regard to Janssen’s statement that the Alliance had submitted for a new indication on the prevention of cardiovascular events, the Alliance noted that in November 2015 the data from the EMPA-REG study was submitted to the EMA for inclusion within Section 5.1 of the Jardiance SPC and also amendment of the text within Section 4.1 of the SPC.

While ‘new indication’ was not defined in EU law, the Alliance referred to an EU regulatory guidance document (Guidance on a new therapeutic indication for a well-established substance, November 2007) which listed the types of changes which might be regarded as a new indication. The additional cardiovascular outcome data did not change the target disease, target population, mode of therapy or method of treatment for type 2 diabetes. This guidance supported the Alliance’s position that the change to the SPC would not constitute a new indication and that it had not promoted a new indication for Jardiance.

The letter at issue led with an introduction to Zinman et al (2015) and the indication for Jardiance and approximate reductions in HbA1c demonstrated in phase 3 studies. An overview was then given of the cardiovascular outcomes and safety data from the EMPA-REG study (about half a page) and the remainder (one page) re-iterated the licensed indication as per Section 4.1 of the Jardiance SPC. It was also specifically stated that Jardiance was not indicated for cardiovascular risk reduction. In that regard, the letter therefore clearly presented the results for the EMPA-REG study in the context of Jardiance as a blood glucose-lowering agent and was consistent with the safety related data in the SPC.

The cardiovascular mortality and hospitalisation for heart failure data collected in the EMPA-REG study and submitted to the regulatory authorities did not change the population eligible for treatment with Jardiance. According to the current SPC, patients with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk could be treated in accordance with the particulars listed in the SPC. Overall the trial design and results were not inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC and therefore the Alliance did not consider that the covering letter was in breach of Clause 3.2.

In summary:

- Any addition of cardiovascular outcome data within Sections 4.1 and 5.1 of the Jardiance SPC would not represent a new indication according to the respective EU Regulatory Guidance Document

- The second paragraph of the letter stated: ‘Empagliflozin is a glucose-lowering agent indicated for the treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus’

- Later the letter stated: ‘Please note that Jardiance (empagliflozin) is indicated for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus to improve glycaemic control in adults as…’, and the exact current indication was provided

- To avoid any doubt to the recipient, this was followed by the clear statement: ‘Empagliflozin is not indicated for the treatment of weight loss, blood pressure control or cardiovascular risk reduction’

- Overall the trial design and results provided valuable data to the health profession which was not inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC.

The Alliance thus denied a breach of Clause 3.2.

Regarding Clause 9.1, the Alliance submitted that it had always maintained high standards. The covering letter did not use inappropriate language, did not tease about anything without providing any actual evidence and was tasteful. It was thus difficult to see how it could cause offence.

The letter was certified in accordance with the requirements of the Code and the data was appropriately promoted as additional information (not as an indication) within the context of the licensed indications. The letter was certified by two UK registered medical practitioners within the Alliance and a non-medical signatory.

The Alliance submitted that the letter was not disguised promotion and so did not breach Clause 12.1. The letter was approved as a promotional item.

The letter, a copy of Zinman et al (2015) and the Jardiance prescribing information, attached together in a clear plastic folder, constituted a single item and had been certified and distributed accordingly. The letter was clearly promotional and had not been disguised as non-promotional. The first sentence of the letter made it clear that a copy of a clinical paper was being provided and not a safety update; the letter did not resemble the MHRA recomended template for ‘Dear Doctor’ letters. The identity of the responsible pharmaceutical companies was also obvious.

A certified briefing document was provided to the sales force regarding the distribution of the letter in a promotional manner. The letter had been distributed to diabetologists, general practitioners, diabetes specialist nurses and GP practice leads ie only relevant health professionals with an interest in diabetes and only at the end of a 1:1 promotional call. A ‘Dear Doctor’ letter would not be provided within a clear folder alongside a publication nor would it be provided by the sales force at the end of a promotional call. The sales force mandatory verbatim (copy provided) also made the contents of the folder clear to the health professional.

In summary:

- The letter looked very different to a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter and did not follow the MHRA guidance on the drafting of such a letter

- The letter was stapled with a copy of Zinman et al (2015) and the prescribing information and provided in a clear folder, therefore entirely different in appearance to a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter

- The letter had been distributed at the end of a promotional call by representatives, a practice completely different from how a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter would be handled

- The promotional material and activity was certified in January 2016.

Therefore, the distribution of the folder and contents had not been done in a manner similar to the distribution of a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter and the Alliance disputed that the activity was in breach of the Code.

With regard to the alleged breach of Clause 2, the Alliance disagreed that the promotional activity at issue brought discredit upon, or reduced confidence in, the industry or would otherwise constitute a breach of Clause 2. It did not fall within the categories of activities mentioned in the supplementary information to Clause 2.

The Alliance believed that it took appropriate steps to ensure compliance with the Code, including contacting the PMCPA for informal advice. Rather than putting patients at risk or damaging the industry reputation, the Alliance considered that the activity would ultimately help patient safety and benefit the reputation of the industry. The Alliance believed the appropriate dissemination of this valuable data in a careful and responsible way in compliance with the Code benefited health professionals and ultimately patients.

In summary, the Alliance did not consider that its distribution of Zinman et al (2015) with a covering letter and attached prescribing information was in breach of Clauses 1.12, 2, 3.2, 9.1 or 12.1. In addition, its promotion of Jardiance had been consistent with the particulars listed in the SPC, no new indication had been promoted and the covering letter and contents of the folder did not resemble a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted that page 1 of the covering letter bore no company name, logo or address and no prominent name or logo of a medicine. The only design element was a header of pale coloured diagonal lines running from the middle of each page to the outside right. The envelope was plain. It was not immediately obvious who the letter was from or what it was about. In that regard the Panel noted that the package of material had been handed out to a health professional after a 1:1 Jardiance call with an Alliance representative and whilst the recipient would have had the benefit of that interaction, anyone else picking up the material might not realise where it had come from. The briefing material regarding the use of the material was dated 12 January 2016 and stated that the EMPA-REG study represented a significant milestone in the treatment of diabetes but that the company was unable to discuss the details of the study until the relevant authorization and training was provided. With regard to ‘the relevant authorization’ referred to, the Panel noted that the CHMP agenda for its February 2016 meeting showed that an application for a licence extension for Jardiance to include prevention of cardiovascular events based on the EMPA-REG study results had been submitted. The briefing material clearly stated that EMPA-REG study should only be given out until 30 June 2016 and that when it was given out there should not be any proactive or reactive discussion about the study with health professionals other than the following mandatory verbatim:

‘You may be aware of the regulatory requirement to conduct cardiovascular outcome studies for all new antidiabetic agents. The cardiovascular outcome study for Jardiance was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in September 2015.

In this folder you will find a reprint of the paper. The study forms part of a potential SPC update and I am unable to discuss it further with you. However, the folder includes an accompanying letter from our Medical Directors which indicates how further information may be obtained together with Jardiance prescribing information.’

The covering letter at issue was addressed ‘Dear UK Healthcare Professional’. The second of the first two very short introductory paragraphs stated that Jardiance was a glucose-lowering agent for the treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes; it was not stated, as in the SPC, that it was indicated solely to improve glycaemic control. The most prominent section on page 1 was headed ‘Recent Cardiovascular Outcomes Data’ and took up the rest (approximately 75%) of the page. In that regard the Panel noted that, due to concerns that glucoselowering medicines might be associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes (type 2 diabetes was itself a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease), the EMPA-REG study was a cardiovascular safety study mandated by the regulators; it was designed to address long-term (median 3.1 years) safety concerns, not to generate efficacy data for a possible new indication. Four bullet points detailed the main results from Zinman et al (2015) including that Jardiance significantly reduced the relative risk of the combined primary endpoint, of cardiovascular death, non-fatal heart attack or non-fatal stroke by 14% vs placebo. This was in contrast to the Jardiance SPC which stated that Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk. Page 2 of the letter stated the licensed indication for Jardiance (to improve glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes) and that the medicine was not indicated for the treatment of weight loss, blood pressure control or cardiovascular risk reduction. It was further stated that if the reader had any questions or would like to discuss the EMPA-REG study with an Alliance medical advisor, this could be arranged by contacting the medical information department. The letter appeared to have been jointly sent from a medical director from each company.

The Panel noted that Clause 3.2 of the Code stated that the promotion of a medicine must be in accordance with the terms of its marketing authorization and must not be inconsistent with the particulars listed in its SPC. In the Panel’s view it was clear from the briefing given to the representatives that the results from Zinman et al (2015) would form the basis of a proposed change to the SPC and in that regard representatives were instructed not to proactively or reactively discuss the study. By proactively distributing the material at issue, however, the Alliance was knowingly using its representatives to solicit queries about the study, the results of which it knew were inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC. The Panel noted that although Clause 3 did not prevent the legitimate exchange of medical and scientific information during the development of a medicine, provided that such information or activity did not constitute promotion which was prohibited under that or any other clause, the distribution of the material at issue by representatives following a 1:1 Jardiance call, clearly constituted the promotion of Jardiance.

The Panel considered that the prominence given within the letter to the cardiovascular outcome data from the EMPA-REG study promoted Jardiance for cardiovascular risk reduction for which it was not licensed. The results of the study went beyond the SPC statement that Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk. The results were not presented in the context of the safety profile for Jardiance. The statement on page 2 of the letter that Jardiance was not indicated for cardiovascular risk reduction was insufficient to mitigate the otherwise misleading and primary impression given by page 1 of the letter and the reference to outcomes data. In the Panel’s view, the material was preparing the market for an anticipated licence extension. A breach of Clause 3.2 was ruled.

The Panel noted the allegation that the covering letter resembled a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter and was therefore disguised promotion. The Panel assumed that the ‘Dear Doctor’ letters referred to were those sent by companies to convey important product safety information at the request of the MHRA. The Panel considered that given the very bland and not obviously promotional appearance of the letter, it was not unreasonable to think that some recipients would assume that it was important safety information, or other non-promotional information, even if it had been handed to them by a representative. In the Panel’s view, not all recipients would be so familiar with the template for ‘Dear Doctor’ letters such that they would immediately recognise any difference. In the Panel’s view the representatives’ mandatory verbatim was not sufficiently clear about the status of the material; in any event the letter should be capable of standing alone with regard to compliance with the Code. In the Panel’s view, despite the material being distributed by representatives, its promotional intent was not immediately obvious and in that regard it was disguised. A breach of Clause 12.1 was ruled.

The Panel noted that Clause 1.12 required companies to appoint a senior employee to be responsible for ensuring that the company met the requirements of the Code. The Panel noted that the Alliance had appointed senior employees to ensure it met the requirements of the Code and so no breach of Clause 1.12 was ruled.

The Panel noted its comments and rulings above and considered that high standards had not been maintained. A breach of Clause 9.1 was ruled. The Panel was further concerned that the Alliance appeared to have knowingly distributed material which was inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC and which it would use to support a licence extension for a currently unlicensed indication. The Panel considered that a ruling of a breach of Clause 2, a sign of particular censure, was warranted and a breach of that clause was ruled.

The Panel noted its reasons for ruling a breach of the Code as set out above. In addition the Panel was extremely concerned that the Alliance had given its representatives material to distribute to health professionals which it knew they could not discuss with those health professionals. In the Panel’s view this gave a wholly inappropriate signal to the representatives regarding compliance and was completely unacceptable; it compromised the representatives’ position and demonstrated a very poor understanding of the Code on behalf of the signatories. In that regard, and in accordance with Paragraph 8.2 of the Constitution and Procedure, the Panel decided to report the Alliance to the Code of Practice Appeal Board for it to consider whether further sanctions were appropriate.

During the consideration of this case, the Panel noted that the package of material provided to the health professionals consisted of three separate pieces stapled together; the covering letter, a copy of Zinman et al (2015) and the prescribing information in that order. The supplementary information to Clause 4.1 stated that each promotional item for a medicine must be able to stand alone and that a letter could not rely on an accompanying piece of material for the provision of the prescribing information. The Panel noted the order in which the materials were presented and that the one page sheet with the Jardiance prescribing information did not bear the header of pale coloured diagonal lines as seen on both pages of the letter. In that regard the prescribing information and the letter appeared to be two wholly separate pieces. The Panel was concerned that the letter thus did not meet the requirements of the Code and it requested that the Alliance be advised of its concerns.

APPEAL BY BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM and LILLY

The Alliance appealed the Panel’s rulings of breaches of Clauses 2, 3.2, 9.1 and 12.1.

The Alliance stated that the material at issue (the covering letter, a copy of Zinman et al (2015) and the Jardiance prescribing information) was withdrawn from use on 20 April pending the Appeal Board’s decision. No other promotional material referred to the EMPA-REG study.

The Alliance submitted its reasons for its appeal were:

- Cardiovascular safety studies were mandated by the regulatory authorities and empagliflozin was studied in the EMPA-REG study as a diabetes agent. The Alliance had a responsibility to disseminate this important safety data to health professionals because it was relevant to patient outcomes.

- The Alliance took compliance extremely seriously and it submitted that it had acted within the letter and spirit of the Code. The Alliance carried out extensive local and global medico-legal and compliance consultation including consultations with the PMCPA before distributing the material at issue.

- The endpoints and data collected were not inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC which included cardiovascular safety outcomes within Section 5.1, no new indication was promoted, and therefore dissemination of the material at issue was not in breach of Clause 3.2.

- The dissemination of the material was carried out in a controlled manner following detailed briefing. The Alliance submitted that it had demonstrated due diligence and had operated in a conscientious manner.

Background

The Alliance submitted that cardiovascular safety studies were mandated by the EMA and FDA to determine the long-term cardiovascular safety of new glucose-lowering agents. In 2010, rosiglitazone (a leading diabetes treatment at that time) was withdrawn from the European market following cardiovascular safety concerns and set a precedent for the requirement for diabetes medicines to undergo safety trials for cardiovascular outcomes. Thus, UK prescribers had a heightened sensitivity to such safety data in relation to diabetes medicine. The results of cardiovascular outcome trials for other diabetes medicines had been disseminated to health professionals and included in promotional materials before the data was included in the relevant SPC.

The Alliance took a responsible and considered approach to the activity

The Alliance noted the events which it submitted led it to take the considered decision to ask its representatives to provide key health professionals with the material at issue at the end of a 1:1 Jardiance sales call.

At the beginning of 2015, the Alliance began to explore the implications of the possible outcomes of the EMPA-REG study. This included internal cross functional and corporate/global level discussions and also a one hour teleconference with the PMCPA in April 2015 on the clear and accepted understanding that its advice was non-binding.

The Alliance noted that the results of the EMPA-REG study were first disclosed in Stockholm in September 2015 at the EASD conference and were recognised by the health professionals attending as being relevant and important.

Following publication of the results in the NEJM, the Alliance submitted that it had consulted extensively between medical, legal, regulatory and compliance at a country and corporate level. In addition, the Alliance met with the PMCPA in October 2015 to understand its view of promotional activity involving the EMPA-REG study. Whilst the Alliance understood that this guidance was non-binding, and it took full responsibility for its decision to disseminate the material at issue, this demonstrated that it took compliance very seriously and went to great lengths to consider and determine how this important safety data could be distributed.

The EMPA-REG study results were not inconsistent with the Jardiance SPC

The Alliance submitted that as submitted above, the data from the EMPA-REG study was submitted to the EMA for inclusion within Sections 4.1 and 5.1 of the Jardiance SPC. The Alliance set out its proposed new wording of Section 4.1. (That wording was provided to, and commented on by, Janssen but is not provided here because of commercial sensitivity).

The Alliance submitted that the requested amendments to the Jardiance SPC were within its existing indication for treatment of type 2 diabetes, based on the EMPA-REG data. The Alliance noted that although this change had been requested, it could not be sure in what form, if at all, it would be granted, by the EMA. The material at issue was therefore considered on the basis that the SPC was, and would remain, unchanged.

The Alliance submitted that the wording relating to cardiovascular outcomes within the current Jardiance SPC was in Section 5.1. This text referred to data submitted to the EMA and was data included within the empagliflozin EPAR. Within the phase 2/3 empagliflozin clinical studies the meta-analysis of adjudicated cardiovascular events demonstrated a hazard ratio of 0.48 (95% C.I. 0.27-0.85).

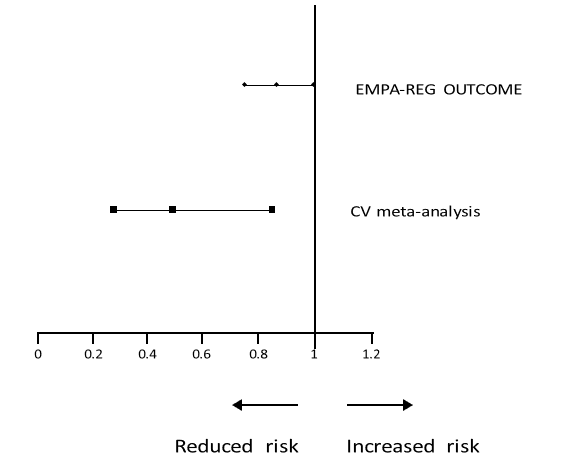

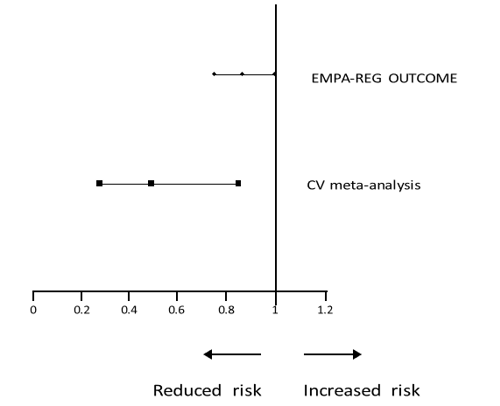

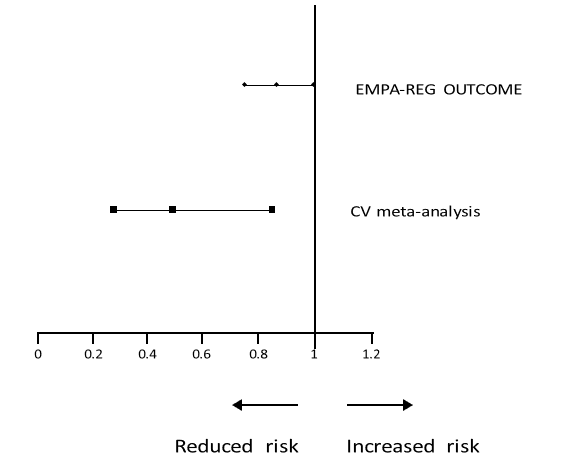

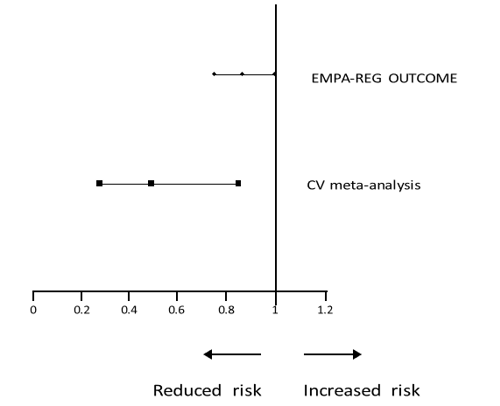

The Alliance submitted that the results of this metaanalysis demonstrated superiority and the wording of the SPC read ‘In a prospective, pre-specified metaanalysis of independently adjudicated cardiovascular events from 12 phase 2 and 3 clinical studies involving 10,036 patients with type 2 diabetes, empagliflozin did not increase cardiovascular risk’. Since the existing meta-analysis data demonstrated superiority (but was categorised in the SPC as ‘… did not increase cardiovascular risk’), the results of EMPA-REG study were therefore not inconsistent with the reference to cardiovascular outcomes within the current Jardiance SPC. The following graphical representation depicted the point estimate of the hazard ratio, the upper bound 95% and the lower bound 95% confidence intervals for the EMPAREG study and the meta-analysis of adjudicated cardiovascular events:

Forest plot displaying, lower 95% CI, point estimate and upper 95% CI for EMPA-REG OUTCOME and CV meta-analysis

Hazard Ratio

The proposed amendments to the empagliflozin SPC were not a new indication

The Alliance re-iterated that the proposed amendments were not a new therapeutic indication. Although ‘therapeutic indication’ was not defined in EU law, EU regulatory guidance stated that a new indication would normally include the following:

- a new target disease,

- different stages or severity of a disease

- an extended target population for the same disease, e.g. based on a different age range or other intrinsic (e.g. renal impairment) or extrinsic

(e.g. concomitant product) factors

- change from the first line treatment to second line treatment (or second line to first line treatment), or from combination therapy to monotherapy, or from one combination therapy (e.g. in the area of cancer) to another combination

- change from treatment to prevention or diagnosis of a disease

- change from treatment to prevention of progression of a disease or to prevention of relapses of a disease

- change from short-term treatment to long-term maintenance therapy in chronic disease.’

The Alliance submitted that the EU regulatory guidance supported its position that it had not promoted a new indication for Jardiance. The additional cardiovascular outcome safety data did not change the target disease, target population, mode of therapy or method of treatment for type 2 diabetes. The current licence for Jardiance which included all adults with type 2 diabetes clearly included the patient population studied with the EMPA-REG study.

The Alliance accepted that it had to comply with the Code in addition to the relevant law, and the Code might be more restrictive than the law in certain areas. Nevertheless, the underpinning law on which the Code was based might be useful as an aid to interpreting the rationale for certain sections of the Code. Clause 3.2 of the Code was based on Article 87(2) of Directive 2001/83 (enacted into UK law by the Human Medicines Regulations 2001, s280) which provided:

‘All parts of the advertising of a medicinal product must comply with the particulars listed in the summary of product characteristics’ (emphasis added).

The Alliance noted that a case before the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) provided some useful guidance on the interpretation of the meaning of Article 87(2) of the Directive, even though the language used in Clause 3.2 of the Code (‘… not inconsistent with …’) differed from that of Article 87(2). The CJEU’s decision in the case made clear that information which conflicted with or distorted the SPC would always fall foul of the ‘must comply with’ requirement, paragraphs 41-42. However, information which confirmed or clarified (and was in any event compatible with) the SPC might be acceptable, even if that information was not identical to the information contained in the SPC, paragraph 5.1. In this particular situation, the current SPC stated that empagliflozin was not associated with an increase in cardiovascular risk so the material in question, reasonably read and in its context, was not inconsistent with this current SPC.

For the above reasons, the Alliance strongly refuted the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 3.2 and disagreed with the ruling of a breach of Clause 2. Controlled distribution by representatives

The Alliance submitted that in order to disseminate the EMPA-REG safety data in a balanced and fair way, it would provide the material at issue only after a 1:1 Jardiance sales call. It also decided to take a conservative approach and avoid any possibility for speculation (whether by representatives or health professionals) about a future change to the SPC or about potential off-label use for cardiovascular indications outside diabetes, by instructing the sales force not to discuss the data further. The provision of the material was conducted in a controlled and monitored manner.

During a three month period material at issue was provided to 2,687 out of approximately 20,000 UK health professionals interested in diabetes. The material was disseminated in less than one in five Alliance calls in the first quarter of the year. All activities were recorded by the representatives in their respective customer relationship database. There had been no known concerns or complaints by health professionals regarding the dissemination of the material.

In relation to the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 12.1 (disguised promotion), the Alliance clarified the context in which the material was provided. As outlined in the briefing document ‘The paper can be provided to diabetologists; diabetes nurse specialists; GP and nurse practice leads in diabetes only and must follow a 1:1 Jardiance call’. Representatives used the Jardiance sales aid for 1:1 calls. Only after the 1:1 Jardiance call using the sales aid, could the material be provided to the health professional. The Alliance submitted that, at the conclusion of the call, health professionals could be in no doubt as to the approved label for Jardiance and of the unambiguous promotional nature of the interaction.

The Alliance submitted that there was no attempt to disguise the material as anything other than promotional. The Alliance letterhead with the diagonal lines was its standard imagery and was used widely in its promotional materials.

The Alliance did not agree with the Panel’s conclusion that health professionals would not be sufficiently familiar with a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter. These types of alerts were regularly issued by the MHRA to health professionals and the Alliance provided copies of those sent on 9 July 2015 and on 14 March 2016 explaining the potential risk of diabetic ketoacidosis associated with SGLT2 inhibitors. The fact that the letter was addressed to ‘Dear Healthcare Professional’ and signed by the Alliance’s medical directors would not have been sufficient to, and was not intended to, confuse any health professional, given that the context of the meeting and the very first sentence of the letter made it clear that a reprint was being provided.

The Alliance strongly refuted the Panel’s statement that the promotional activity sent a ‘wholly inappropriate signal to the representatives regarding compliance and was completely unacceptable’. The Alliance submitted that the provision of this important new safety data was carried out in a way which was not inconsistent with the current Jardiance SPC, was not for a new therapeutic indication and did not constitute the promotion of an unlicensed indication under Clause 3.2. The Alliance took compliance issues extremely seriously and it decided to provide diabetes health professionals with the EMPA-REG safety data in a considered, consultative and conscientious manner.

COMMENTS FROM JANSSEN

Janssen maintained that the Alliance’s promotion of the cardiovascular event prevention data with the EMPA-REG study, prior to the granting of a licence on the new indication, using a ‘Dear Doctor’ style letter, clearly constituted disguised promotion of Jardiance in discord with the current Jardiance indication and marketing authorization and represented a significant failure to maintain high standards. In addition, the content of the briefing document to field teams suggested either the Alliance knowingly distributed this material despite its inappropriate nature, or a lack of understanding of the Code, thus bringing discredit to, and reducing confidence in, the industry. Janssen thus alleged that the Alliance had breached Clauses 2, 3.2, 9.1 and 12.1.

Promotion of the EMPA-REG study was not within current Jardiance approved indication and was inconsistent with the SPC

Janssen reiterated that Section 4.1, Therapeutic indications, of the Jardiance SPC clearly stated the current licensed indication of Jardiance was to improve glycaemic control.

‘Jardiance is indicated in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus to improve glycaemic control in adults as:

Monotherapy

When diet and exercise alone do not provide adequate glycaemic control in patients for whom use of metformin is considered inappropriate due to intolerance.

Add-on combination therapy

In combination with other glucose-lowering medicinal products including insulin, when these, together with diet and exercise, do not provide adequate glycaemic control (see Sections 4.4, 4.5 and 5.1 for available data on different combinations)’.

Janssen alleged that contrary to the current Jardiance licence and as stated in Zinman et al (2014), the primary composite outcome of the EMPA-REG study was cardiovascular event prevention (and not improved glycaemic control). Janssen emphasized that HbA1c reduction, the gold standard marker for diabetes control, blood glucose-lowering in type 2 diabetes clinical trials, was not a primary endpoint nor considered as a key secondary endpoint of the study. Janssen thus alleged that the EMPA-REG study was not designed with the intent for glycaemic control and thus promotion of this study, with a focus of cardiovascular event prevention, was not in line with the current Jardiance marketing authorization.

Proposed amendments to the Jardiance SPC were a new indication

Janssen noted that the Alliance refuted that the proposed amendments to the Jardiance SPC were a new therapeutic indication despite its action which clearly indicated the opposite. The Alliance had filed a new indication submission to the regulatory authority and the wording amendment on Section 4.1 proposed by the Alliance clearly put prevention of cardiovascular events as a separate indication.

Janssen refuted the Alliance’s claim that cardiovascular prevention did not constitute a new indication under EU regulatory guidelines which stated:

‘… a “new therapeutic indication” may refer to diagnosis, prevention or treatment of a disease. In this context a new indication would normally include the following:

Janssen alleged that the use of Jardiance in the prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes, in addition to improved glycaemic control for which Jardiance was currently licensed, undoubtedly constituted the prevention/treatment of a target disease (cardiovascular events) in this case. This was further evidenced by the wording used in the CHMP meeting:

‘Extension of indication to include a new indication on prevention of cardiovascular events based on the final data of the cardiovascular safety phase 3 clinical trial EMPA-REG OUTCOME’ (emphasis added).

Janssen rebutted the Alliance’s argument that the EU regulatory guidance supported its position that it had not promoted a new indication for Jardiance and that the additional cardiovascular outcome safety data did not change the target disease because the current licence for Jardiance included all adult patients with type 2 diabetes and clearly showed that the patient population studied with the EMPAREG study was already included within the current licensed population.

Janssen noted that Jardiance was only currently indicated for one element of type 2 diabetes management – to improve glycaemic control. It was inappropriate and misleading to infer that the licensed indication of Jardiance included cardiovascular event prevention just because the study population in the EMPA-REG study and current licence of Jardiance were both adults with type 2 diabetes.

Janssen acknowledged that the meta-analysis of adjudicated cardiovascular events based on phase 2/3 Jardiance studies demonstrated a hazard ratio of 0.48 (95% CI 0.27-0.85) and was captured in the EPAR. These results were not captured in the Jardiance SPC and were largely based on adverse events reported during the phase 2/3 studies. Moreover, Section 5.1, Pharmacodynamic properties, of the SPC stated that Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk vs cardiovascular event prevention which the Alliance had promoted. Therefore, it could not be interpreted as providing evidence of cardiovascular event reduction with Jardiance.

‘Cardiovascular safety

In a prospective, pre-specified meta-analysis of independently adjudicated cardiovascular events from 12 phase 2 and 3 clinical studies involving 10,036 patients with type 2 diabetes, empagliflozin did not increase cardiovascular risk.’

Thus, the proposed amendments to the Jardiance SPC was a new indication and the promotion of cardiovascular event prevention before licence extension approval constituted an off-licence promotion of Jardiance.

Disguised promotion using a ‘Dear Doctor’ style letter

Janssen alleged that the material at issue lacked any of the usual Jardiance promotional branding, colours and brand imagery, and was signed by the medical directors in the Alliance, rather than by their commercial counterparts. The letter had no company logos nor any clear warning on the first page to indicate it was promotional in nature. The design closely resembled a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter normally reserved for communication of important product safety information requested by the MHRA. Janssen therefore refuted the Alliance’s claim that ‘The Alliance letterhead with the diagonal lines was the standard imagery used by the Alliance and was used widely in Alliance promotional material’.

Janssen expressed concern of the possible negative impact on patient safety by the Alliance using promotional material designed in a similar style to a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter. Jardiance and other medicines in the same class were subjected to additional safety monitoring by the regulatory authority, in fact, two ‘Dear Doctor’ letters on this particular class of medicine were issued as requested by the MHRA in the last 12 months. Using a letter that closely resembled a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter for promotion might weaken the effectiveness of the MHRA mandated communication of important safety signals in the future.

The Alliance’s failure to maintain high ethical and compliance standards

Janssen noted that the EMPA-REG study results were first released in September 2015 at the EASD annual meeting and subsequently published in the NEJM following the meeting presentation. Since then, the Alliance submitted a label update to include a new indication of cardiovascular event prevention, as noted in the CHMP meeting agenda of February 2016.

Janssen noted the sales force briefing document for the material at issue (issued 12 January 2016) stated:

‘… we are unable to discuss the details of this clinical paper until the relevant authorisation and training is provided.’

‘… time limited exception in the UK that the sales force can disseminate … without discussion … now until the end of June 2016.’

‘… there should not be any discussion with regards to the EMPA-REG OUTCOME (ERO) data between sales field force and HCPs.’

Janssen alleged that this clearly indicated that the Alliance knew that a new indication had been applied for and was pending regulatory authorization and therefore should not have been discussed with health professionals, particularly by the sales force. The following mandatory verbatim issued to the sales force, to be used during dissemination of the material, further supported Janssen’s allegation:

‘The study forms part of potential SPC update and I am unable to discuss it further with you.’

Janssen alleged that the briefing document suggested that either the Alliance knowingly distributed the material despite its inappropriate and non-compliant nature, or it represented a severe lack of understanding of the Code thus, bringing discredit to, and reducing confidence in, the industry.

Janssen acknowledged that the Alliance had consulted the PMCPA and local and global medicolegal and compliance prior to initiating EMPAREG study promotional activity. Despite these consultations, Janssen alleged that the Alliance had prepared promotional material disguised as a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter which promoted an unlicensed indication for Jardiance.

Janssen alleged that the manner and intent in which the material was disseminated and the way in which the sales force was briefed, were taken under the approval of the respective medical directors from the Alliance. On this occasion, they and the final signatories, who were responsible for ensuring that their companies met the requirements of the Code, failed to take a responsible and considered approach to these activities.

In conclusion, Janssen alleged that the Alliance had brought the industry into disrepute by promoting the EMPA-REG study results prior to the granting of a new indication of the prevention of cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes in breach of Clauses 2, 3.2, 9.1 and 12.1 of the Code.

APPEAL BOARD RULING

The Appeal Board noted the Alliance’s submission that the outcome of the EMPA-REG study was important safety data that it wanted to share with health professionals. The Appeal Board noted that the primary composite outcome of the study was death from cardiovascular causes, non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke. Patients were type 2 diabetics at high cardiovascular risk. According to Zinman et al (2015) all patients had established cardiovascular disease and had received no glucose-lowering agents for at least 12 weeks before randomization, with HbA1c of at least 7% and no more than 9%, or had received stable glucose-lowering therapy for at least 12 weeks before randomization with HbA1c of at least 7% and no more than 10%. Many patients did not reach their glycaemic targets with an adjusted mean HbA1c level at week 206 of 7.81% in the pooled empagliflozin group and 8.16% in the placebo group. The study concluded that patients who received Jardiance had significantly lower rates of the primary composite CV outcome and of death from any cause compared to placebo.

The Appeal Board acknowledged that the data would be of interest and importance to health professionals. It noted the Alliance representatives’ statement at the appeal that the EMPA-REG study was a highly cited study and that the study was required by regulators. Dissemination of the data had to comply with the Code. The Appeal Board noted that the material at issue was handed out to a health professional after a 1:1 promotional Jardiance call with an Alliance representative and the representative was instructed not to discuss it. The Appeal Board noted from the Alliance’s representatives at the appeal that health professionals in primary care were targeted as they were responsible for the majority of prescriptions of diabetes medicines and unlike secondary care health professionals, were mostly unaware of the EMPA-REG study. The Appeal Board noted from the representatives from the Alliance that distribution of the material at issue by the sales representatives would be likely to increase the market share of Jardiance.

The Appeal Board disagreed with the Alliance’s submission that the proposed wording for the Jardiance SPC was not a new indication. In this regard it noted that the agenda for the CHMP meeting dated 22 February 2016 stated that in relation to Jardiance it was considering an: ‘Extension of indication to include a new indication on prevention of cardiovascular events, based on the final data of the cardiovascular safety phase III clinical trial EMPA-REG OUTCOME.’

The Appeal Board noted that the proposed new wording did not refer to a prerequisite lack of glycaemic control as in the current indications. The Appeal Board noted the Alliance’s submission regarding the data from the CV meta-analysis which was the basis for the statement in the current SPC that ‘Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk’. The Forest plot displaying the hazard ratio and confidence intervals indicated that the CV meta-analysis data showed reduced risk with the confidence interval between just over 0.2 and just over 0.8. The same plot showed the EMPA-REG study hazard ratio as 0.86 and confidence intervals nearer to 1 (0.74 to 0.99). The CV meta-analysis data were further to the left of reduced risk side than the EMPA-REG data.

The Appeal Board noted that approximately three quarters of the letter discussed cardiovascular outcome data and in this regard did not accept the companies’ submission that the emphasis of the letter was on cardiovascular safety. The Appeal Board considered that the prominence given within the ‘Dear UK Healthcare Professional’ letter to the cardiovascular outcome data (efficacy data) from the EMPA-REG study was such that it promoted Jardiance for cardiovascular risk reduction, which was inconsistent with the current Jardiance SPC which stated in Section 5.1 that Jardiance did not increase cardiovascular risk. This was based on the CV meta-analysis data. In the Appeal Board’s view there was a difference between risk reduction and not increasing risk. The statement on page 2 of the letter that Jardiance was not indicated for cardiovascular risk reduction was insufficient to negate the misleading impression. In the Appeal Board’s view, the material was preparing the market for an anticipated licence extension. Consequently, the Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 3.2. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

The Appeal Board considered that as the ‘Dear UK Healthcare Professional’ letter included no obvious branding to identify that it was from the Alliance, some recipients might assume that it was important safety information such as a ‘Dear Doctor’ letter sent at the request of the MHRA. The Appeal Board noted from the Alliance’s representatives at the appeal that with the benefit of hindsight it would have included a company logo and changed how the letter was addressed to make it more obviously promotional.

The Appeal Board noted that the letter should be capable of standing alone with regard to compliance with the Code. In the Appeal Board’s view, despite the letter being distributed by representatives, the fact that it was promotional was not immediately obvious. This was especially so for subsequent readers of the material who did not receive it from the representative. The Appeal Board considered that the material was disguised and upheld the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 12.1. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful. The Appeal Board noted its comments and rulings above and considered that high standards had not been maintained. The Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 9.1. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

The Appeal Board noted that the Alliance had used the data from the EMPA-REG study to support an application for a licence extension. In the Appeal Board’s view, the letter was so positive about cardiovascular risk reduction that this would encourage health professionals to switch previously controlled diabetes patients at risk of cardiovascular events to Jardiance to reduce that cardiovascular risk. This was inconsistent with its SPC and was an unlicensed indication. The Appeal Board noted that in response to a question, the representatives from the Alliance confirmed that they were familiar with the numerous case precedents where companies claimed additional benefits for medicines outside of licence and had been ruled in breach of the Code. The Appeal Board was surprised that the collective knowledge and experience of both Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim could consider that the provision of the material at issue was anything other than promotion of an unlicensed indication. The Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of a breach of Clause 2. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

COMMENTS FROM BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM and LILLY ON THE REPORT FROM THE PANEL

At the consideration of the report the representatives from the Alliance submitted that it was fully committed to operating in an ethical and compliant manner and it took compliance with the Code very seriously. The Alliance had a robust governance framework within which compliance formed the backbone. Compliance featured on the monthly Alliance Country Governance meeting chaired by the managing directors. The respective medical directors were standing members and assumed responsibility for compliance at these meetings. The Alliance held a monthly compliance meeting which was attended by each medical director, compliance director/senior leader and senior medical and marketing leaders. The Alliance had a global and a local ‘Policy Alignment Document’ setting clear expectations on how it would operate according to company procedures and the Code. All employees were required to undergo regular training on the Code including attendance at PMCPA seminars.

The Alliance had regularly consulted with the PMCPA around proposed/potential activities and it would continue to do so. Both Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim actively participated in the PMCPA Compliance Network meetings. The Alliance regularly trained employees on all standard operating procedures (SOPs). The Alliance had a joint SOP for the approval of promotional materials in the UK. The Alliance required three signatories for its promotional materials which went beyond the Code requirement of one signatory. The Alliance had regular forums for signatories in order to share best practice.

The Alliance submitted that the central issue in these cases was the interpretation of Clause 3.2 in relation to the EMPA-REG study data, which was a technical point in a grey area of the Code. A difference in interpretation in an unclear area of the Code did not mean that the Alliance had inadequate compliance processes in place.

APPEAL BOARD CONSIDERATION OF THE REPORT FROM THE PANEL

The Appeal Board noted its comments and rulings of breaches of the Code in the above including a breach of Clause 2. The Appeal Board considered that the Alliance’s actions either showed a disregard for, or a fundamental lack of understanding of, the requirements of the Code. The amount of time the companies had spent discussing the position implied they were aware of the risks involved. The Appeal Board did not accept that the issues in this case were due to a grey area of the Code. It appeared that the Alliance had decided to put commercial gain before compliance with the Code. This was totally unacceptable.

The Appeal Board was very concerned that 2,687 health professionals had been provided with the material at issue which had promoted Jardiance for an unlicensed indication. This was unacceptable. Consequently, the Appeal Board decided, in accordance with Paragraph 11.3 of the Constitution and Procedure, to require the Alliance to issue a corrective statement to all recipients of the material at issue. [The corrective statement, which was agreed by the Appeal Board prior to use, appears at the end of this report].