CASE AUTH/2671/11/13 ANONYMOUS CONTACTABLE MEMBER OF THE PUBLIC v SERVIER

Clinical trial disclosure (Valdoxan)

An anonymous, contactable member of the public complained about the information published as ‘Clinical Trial Transparency: an assessment of the disclosure results of company-sponsored trials associated with new medicines approved recently in Europe’. The study was published in Current Medical Research & Opinion (CMRO) on 11 November 2013. The study authors were Dr B Rawal, Research, Medical and Innovation Director at the ABPI and B R Deane, a freelance consultant in pharmaceutical marketing and communications. Publication support for the study was funded by the ABPI.

The study surveyed various publicly available information sources for clinical trial registration and disclosure of results searched from 27 December 2012 to 31 January 2013. It covered 53 new medicines (except vaccines and fixed dose combinations) approved for marketing by 34 companies by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2009, 2010 and 2011. It included all completed company-sponsored clinical trials conducted in patients and recorded on a clinical trial registry and/or included in a European Public Assessment Report (EPAR). The CMRO publication did not include the specific data for each product. This was available via a website link and was referred to by the complainant. The study did not aim to assess the content of disclosure against any specific requirements.

The complainant stated that the study detailed a number of companies which had not disclosed their clinical trial results in line with the ABPI for licensed products. The complainant provided a link to relevant information which included the published study plus detailed information for each product that was assessed.

The summary output for each medicine set out the sources for all trials found, irrespective of sponsor and an analysis of publication disclosure in the form of a table which gave details for Valdoxan (agomelatine).

The detailed response from Servier is given below.

General detailed comments from the Panel are given below.

The Panel noted the CMRO publication in that twelve evaluable studies had not been disclosed within the timeframe. The disclosure percentage was 63%. Six studies completed before the end of 2012 had not been disclosed. The disclosure percentage at 31 January 2013 of trials completed before the end of January 2012 was 83%. A footnote stated that the undisclosed trials were in the process of being prepared for publication.

The Panel noted that Valdoxan was approved for use in Europe in February 2009. In response to a question whether this was when the product was first approved and commercially available anywhere in the world. Servier stated that the relevant date was March 2009.

The Panel was only concerned with studies which involved UK patients or involved the UK company. Two studies (25 and 26) which completed in September 2008 and April 2009 had, according to Servier, not been disclosed within the timeframe. It appeared from the information provided by Servier that the abstracts for the studies were published in June 2010 and March 2011 with publication in 2011 and 2013 respectively.

The Panel noted that the relevant Code was 2008 and the Joint Position 2005. Servier should have disclosed the results for one study (Study 25) by March 2010 and the other study (Study 26) by April 2010. As the results were not disclosed within this timeframe Servier had not met the requirements of the Code. The Panel ruled a breach of the 2008 Code as acknowledged by Servier. The delay in disclosure meant that high standards had not been maintained and a breach was ruled. As the results had been disclosed the Panel considered that on balance there was no breach of Clause 2 and ruled accordingly.

The results of a further three studies (29, 30 and 31) which involved UK patients and completed in September 2011, August 2011 and December 2008 were still to be disclosed. The Panel considered that Servier, by not disclosing the results within 12 months of study completion (Study 30) or by one year after first approval (Study 31) ie by August 2012 and March 2010 respectively, the company had not met the requirements of the Code. The Panel ruled a breach of the 2011 Code in relation to the study which completed in August 2011 (Study 30). The study which completed in December 2008 (Study 31) was ruled in breach of the 2008 Code.

Study 29 completed in September 2011 and was carried out on a different formulation. The relevant Code was the 2011 Code and thus the Joint Position 2008 which stated that if trial results for an investigational product that had failed in development had significant medical importance, study sponsors were encouraged to post the results. The Panel was unsure whether the product had ‘failed in development’ or whether the results were of significant medical importance. Further companies were only encouraged to post results if possible. The complainant had not provided any details in this regard. The Panel considered that publication of such data was preferable, however failure to publish was not necessarily out of line with the Joint Position 2008. Thus the Panel ruled no breach of the 2011 Code including Clause 2.

The Panel noted that Servier knew from the CMRO publication that some of its trial data results had not been disclosed. The ABPI study was conducted between December 2012 and January 2013 but in the 9½ months that had elapsed between the end of the study and the receipt of this complaint, the company had not subsequently disclosed the missing data (Studies 30 and 31). Notwithstanding the company’s submission that the missing data was being prepared for publication, the Panel considered that failure to disclose the data meant that high standards had not been maintained and a breach was ruled.

The Panel also considered that failure to disclose meant that Servier had brought discredit upon, and reduced confidence in, the pharmaceutical industry and a breach of Clause 2 was ruled.

The Panel noted there was no way of identifying from the list of 49 studies provided by Servier which were the remaining seven studies cited in the CMRO publication. If these studies had no UK involvement the matter did not come within the scope of the UK Code. If these studies had UK involvement but were completed before 5 January 2006 they would be exempted under the 2005 Joint Position. The Panel noted that the results from all studies, apart from the three (29, 30, 31) considered above, had been disclosed. The results of studies that completed before 5 January 2005 did not need to be disclosed. Thus the Panel ruled no breach of the 2008 Code including Clause 2.

An anonymous, contactable member of the public complained about the information published as ‘Clinical Trial Transparency: an assessment of the disclosure results of company-sponsored trials associated with new medicines approved recently in Europe’. The study was published in Current Medical Research & Opinion (CMRO) on 11 November 2013. The study authors were Dr B Rawal, Research, Medical and Innovation Director at the ABPI and B R Deane, a freelance consultant in pharmaceutical marketing and communications. Publication support for the study was funded by the ABPI.

The study surveyed various publicly available information sources for clinical trial registration and disclosure of results searched from 27 December 2012 to 31 January 2013. It covered 53 new medicines (except vaccines and fixed dose combinations) approved for marketing by 34 companies by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2009, 2010 and 2011. It included all completed company-sponsored clinical trials conducted in patients and recorded on a clinical trial registry and/or included in a European Public Assessment Report (EPAR). The CMRO publication did not include the specific data for each product. This was available via a website link and was referred to by the complainant. The study did not aim to assess the content of disclosure against any specific requirements.

COMPLAINT

The complainant stated that the study detailed a number of companies which had not disclosed their clinical trial results in line with the ABPI for licensed products. The complainant provided a link to relevant information which included the published study plus detailed information for each product that was assessed.

The summary output for each medicine set out the sources for all trials found, irrespective of sponsor and an analysis of publication disclosure in the form of a table which gave details for the studies for each product. The data for Valdoxan (agomelatine) were as follows (for expanded chart see PDF of case report):

Total by Total Unevaluable Evaluable Disclosed in Disclosure Complete before Disclosure % at Phase timeframe percentage end Jan 2012 31 Jan 2013

I & II 5 2 3 2 67% 3 2 67%

III 35 7 28 18 64% 29 24 83%

IV 2 1 1 0 0% 1 1 100%

Other 4 4 0 0 0% 2 2 100%

TOTAL 46 14 32 20 63% 35 29 83%

The explanation of terms given in the documentation was as follows:

Total

Total number of trials identified which were completed and/or with results disclosed

Unevaluable

Trials within the total which could not be evaluated (due to either trial completion date or publication date being missing or unclear) – excluded from the analysis

Evaluable

Trials with all criteria present including dates, and hence the base which could be evaluated for the assessment

Results disclosed in timeframe

Evaluable trials which fully complied with publication requirements, ie summary results disclosed (in registry or journal) within 12 months of either first regulatory approval date or trial completion date, whichever was later

Disclosure percentage

Proportion of evaluable trials which were fully disclosed

Completed before end of January 2012

Number of studies completed before end January 2012 (or already disclosed)

Results disclosed at all

Number of trials with any publication of results at any time

Disclosure percentage at 31 January 2013

Proportion of trials completed by end January 2012 which were now disclosed

* * *

The complainant alleged that all of the companies listed had breached Clauses 2, 9 and 21 of the Code.

When writing to Servier, the Authority drew attention to Clauses 1.8 and 21.3 of the Second 2012 Edition of the Code and noted that previous versions of the Code might also be relevant.

RESPONSE

Servier UK submitted that the objective of the ABPI study was to assess the timely disclosure in the public domain of the results of company-sponsored clinical trials carried out on 53 new products approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) between 2009 and 2011 inclusive, one of which was Servier’s Valdoxan (agomelatine) which was approved for use in February 2009 by way of the centralised procedure.

This was a unique and politically-sensitive issue and the broader context could not be ignored. Therefore, Servier requested that the PMCPA adjudicated this matter without condemnation of Servier and closed the matter entirely.

Servier noted that the ABPI’s research was undertaken in the context of the important on-going debate and publicity regarding the transparency and disclosure of clinical trial information and in response to the call for evidence by the House of Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology (inquiry into clinical trials and disclosure of data). According to the ABPI press release of 11 November, the study was intended as a constructive contribution to the transparency debate. Indeed the study clearly highlighted a positive trend of increasing levels of disclosure for industry-sponsored clinical trials. In that same press release, the ABPI acknowledged that as part of a global industry it had actively engaged with stakeholders over several years to increase clinical trial transparency. The study itself was evidence of such engagement which, according to the ABPI, was a ‘catalyst for further change, leading to greater transparency across the pharmaceutical industry’. Servier was one such stakeholder and it was therefore incomprehensible that it was being investigated for a breach of the ABPI Code for assisting the ABPI in pursuance of its fundamental aims.

In undertaking the research, whilst the ABPI relied on publicly available information sources it also worked with the relevant companies in order to produce a comprehensive view of current levels of clinical trial results disclosure. Servier UK, along with its headquarters, worked together with the ABPI early in 2013 to ensure that all requests for further information, and verification of information already held by the ABPI, were responded to and confirmed respectively in a complete and timely manner. This collaborative approach reflected Servier’s commitment to transparency and compliance, with current guidance and regulations. In view of the nature and purpose of the study, it was clear that it was never intended to be a trigger for raising compliance issues under the ABPI’s own Code, rather it sought to produce a benchmark for industry on rates of public reporting of industry-sponsored trials within 12 months of market authorisation.

If there was a risk that companies participating in the study would be exposed to compliance issues, such companies would naturally have been reluctant to collaborate with the ABPI to the detriment of the fundamental aim of the study.

Servier noted that the ABPI did not necessarily expect a disclosure rate of 100% given the wide range of years over which trials included in its assessment were conducted (with some having been conducted more than ten years ago) together with the broad scope of inclusion for the study. Had the ABPI so wished, it could have reported relevant companies to the PMCPA which it did not do. Indeed, the ABPI had announced that for products launched in 2012 and 2013, it would take on the responsibility for reporting to the PMCPA non-compliance with trial registration and posting of summary results. This further confirmed that for the period prior to that (and relevant to the present complaint) it would not raise compliance issues.

Servier respected the PMCPA’s remit to investigate complaints from whatever means and did not dispute that it operated separately from the day to day management of the ABPI. However, the PMCPA was established by the ABPI to further the ABPI’s aim of ensuring that the industry operated in a ‘professional, ethical and transparent manner’ (as set out in the introduction to the ABPI Code). As Servier had voluntarily assisted the ABPI in the pursuance of one of its fundamental aims, it should not be condemned by the PMCPA under the ABPI Code but rather be granted ‘immunity’ from the sanctions that would ordinarily be applicable for breaches of the Code – ie it should not be liable to pay any administrative charges, nor should it be subject to any other sanction. In the present circumstances, sanctioning a company under the ABPI Code would be counterproductive. It would undermine the industry’s trust in the ABPI, because the ABPI Code was being used in a fashion that would constitute a misuse of self-regulation. It would be ironic and unfair if companies were condemned by the PMCPA under the ABPI Code, when the purpose of the ABPI undertaking the study and publishing was to support and encourage transparency. Indeed there was a greater risk that it would stifle any future exchange between pharmaceutical companies and the ABPI leading to less open dialogue between the ABPI and stakeholders. In any event, it was unnecessary to condemn companies under the Code because the study already revealed that there were lessons to be learnt – as the ABPI acknowledged in its press statements.

Industry as a whole was clearly engaged in this important debate and worked constructively on means to improve the transparency of clinical trial results disclosure. Servier was committed to such transparency and commended the ABPI’s efforts in this area. Condemning companies in this way, under the ABPI Code, however, would unfortunately undermine this effort.

However, in so far as the PMCPA deemed that the ABPI Code applied and proceeded with the complaint, Servier responded to Clauses 1.8, 21, 2 and 9.

Servier provided the details for all the on-going and completed clinical trials examined by the ABPI for the purposes of the study and indicated which of those had a UK association. Whilst the ABPI Code did not apply to clinical trials which did not have a UK association, Servier had nevertheless provided details of those clinical trials if they were examined by the ABPI for the purposes of the study as per the PMCPA’s request. Details of clinical trials conducted prior to 2008 were provided. Indeed, prior to 2008 there was no obligation on companies to disclose details relating to clinical trials under the ABPI Code. Companies were merely encouraged to disclose such information.

Therefore, in Servier’s view, only those clinical trials that had a UK association and were conducted after 2008 fell within the scope of the present complaint. However, despite that fact, Servier nevertheless provided details of all trials examined by the ABPI for the purposes of its study, in the interests of cooperation.

Any broader request for information was not only outside the scope of the present complaint but would be burdensome and inappropriate. Servier was an international company with research facilities in different jurisdictions. Obtaining information concerning clinical trials which extended beyond those already examined by the ABPI, particularly where those clinical trials might have had no UK association, was a hugely burdensome exercise especially in the timeframe given and would result in an inefficient waste of resources.

Clause 1.8

The PMCPA had specifically asked Servier to comment on Clause 1.8 ie the jurisdictional aspect ‘given the global nature of pharmaceutical research’.

Clause 1.8 stated: ‘Pharmaceutical companies must comply with all applicable codes, laws and regulations to which they are subject’. It was clear from the supplementary information to Clause 1.8 that, if there was no UK link in terms of the activity, then the ABPI Code did not apply. As noted above, given the global nature of clinical research and in particular Servier’s operations, it was clear that only a proportion of the clinical trials which were examined by the ABPI for the purposes of its study had any association with the UK. Servier provided information on those studies which had a UK association. The remainder were outside the scope of the present complaint and should be considered no further.

Depending on the clinical trial, different versions of the ABPI Code would apply. The current version of the ABPI Code referred both to the Joint Position on Disclosure and to the Joint Position on Publication, whereas the earlier versions of the Code referred only to the Joint Position on Disclosure (and even then, only in the supplementary information). In addition, and as developed below, earlier versions of the Code did not contain any obligation at all, but merely encouraged companies to disclose information relating to clinical trials. The obligation to disclose results of clinical trials only appeared therefore in the 2008 and subsequent codes of practice.

Clause 21.3

Servier had provided detailed information relating to all on-going and completed clinical trials examined by the ABPI for the purposes of the study. It was clear from the table in the study that only three studies carried out with UK involvement, completed after 2008, were found to be non-compliant with regards to disclosure. While Servier accepted that this was not necessarily in accordance with Clause 21.3, the broader context was relevant.

The first study (row 29 of Appendix 1) was completed in September 2011. This was a trial looking at a formulation different to the one authorised by the EMA and not on the market. The second trial (row 30) was completed in August 2011. A publication was currently in preparation. The third trial (row 31) was completed in December 2008 and was due for imminent publication in early 2014.

In addition, Servier reminded the PMCPA of the rapidly changing environment (eg transparency was a live issue and the goal-posts changed as the debate moved forward) resulting in many changes and updates in both ABPI and international guidance over recent years. For example, the 2006 Code simply encouraged companies to comply with the Joint Position ie no requirement was incorporated into the ABPI Code as it was now. Whilst, the 2008, 2011 and 2012 Codes, required disclosure, they were less prescriptive than the current (Second 2012 Edition), merely stating in Clause 21.3 that ‘Companies must disclose details of clinical trials’ without stipulating how (although the supplementary information referred to the Joint Position on Disclosure of clinical trial results). The current ABPI Code set out important principles that Servier agreed should be adhered to, and as appreciated, this represented a challenge to industry as it raised issues of infrastructure and co-ordination for an international company, that Servier accepted must be addressed.

With reference to the Joint Position on Publication, the PMCPA should not ignore the difficulties associated with publication which were relevant to the public transparency debate. For example, it should be acknowledged that publication of a paper required a huge resource. There was also a certain element of publication bias which originated from journals and their editors: editors might also be reluctant to publish negative studies.

In conclusion, Servier submitted it explained the context of these instances of non-disclosure. In any event, as a result of the rapidly changing legal and self-regulatory environment Servier was currently in the process of considering its internal procedures and infrastructure and doing the utmost to implement this as soon as possible.

Clause 9

Clause 9 concerned the requirement to maintain high standards. Servier strongly refuted the alleged breach of Clause 9.

Servier was committed to achieving the highest standards with regards to the disclosure of clinical trial results. Reflective of the ever-changing environment as the debates moved forward in this area, Servier did not yet have comprehensive policies in place. In addition, to comply with the imminent update of EudraCT in 2014, Servier would take all necessary measures to ensure that all the regulatory requirements for clinical trial transparency would be met.

A breach of Clause 21.3 did not reflect a failure to maintain high standards; indeed it did not follow that every breach of the ABPI Code was a failure to maintain high standards. Servier had maintained high standards throughout: it had collaborated with the ABPI in relation to the study to provide up-to-date information in order to help improve transparency. However, this was clearly a live issue and the goal-posts were changing as the transparency debate moved forward. It was not appropriate in the circumstances to hold Servier in breach of Clause 9 and as noted above, it would be counterproductive to any future transparency initiatives of the ABPI.

Clause 2

Servier submitted that Clause 2 was reserved for cases of particular censure. This was not such a case; it was not one of the breaches listed in the supplementary information to Clause 2, nor was it analogous. The arguments developed above explained why it would be counterintuitive to any future transparency initiatives to find Servier in breach of Clause 2 (and any other clauses). It would be highly ironic considering Servier’s voluntary collaboration with the ABPI and unfair for a breach of Clause 2 to be ruled in circumstances where the ABPI did not intend to raise compliance issues. To condemn Servier would seriously deter companies from collaborating with the ABPI in the future and undermine the ABPI’s efforts with regard to transparency, which was the very purpose of the study and article.

Servier respectfully requested that the PMCPA looked at the broader context of this complaint and the politically sensitive environment before taking any decision on this matter particularly in respect of Clauses 2 and 9.

Conclusion

Servier acknowledged at most a technical breach of Clause 21.3 if the PMCPA considered that the broader context of the complaint was not relevant and Servier’s collaborative efforts with the ABPI were not taken into account. Servier strongly refuted a breach of either Clause 2 or 9 in any circumstances. However, in its view, the broader context of this matter could not be ignored and Servier requested that the PMCPA adjudicated this matter without condemnation of Servier and closed the matter entirely.

In a response to a request for further information, Servier confirmed that Valdoxan was first approved and commercially available in March 2009.

GENERAL COMMENTS FROM THE PANEL

The Panel noted the ABPI involvement in the study. However, a complaint had been received and it needed to be considered in the usual way in line with the PMCPA Constitution and Procedure. The Panel noted that all the cases would be considered under the Constitution and Procedure in the Second 2012 Edition as this was in operation when the complaint was received. The addendum (1 July 2013 which came into effect on 1 November 2013) to this Code only related to Clause 16 and was not relevant to the consideration of these cases.

The Panel noted that the study concluded that the results of over three quarters of all company sponsored clinical trials were disclosed within a year of completion or regulatory approval and almost 90% were disclosed by 31 January 2013 which suggested transparency was now better than had sometimes been reported previously.

The Panel considered that the first issue to be determined was whether the matter was covered by the ABPI Code. If the research was conducted on behalf of a UK pharmaceutical company (whether directly or via a third party) then it would be covered by the ABPI Code. If a study was run by a non UK company but had UK involvement such as centres, investigators, patients etc it was likely that the Code would apply. The Panel appreciated the global nature of much pharmaceutical company sponsored clinical research and a company located in the UK might not be involved in research that came within the ABPI Code. It was a well established principle that UK pharmaceutical companies were responsible for the activities of overseas affiliates if such activities related to UK health professionals or were carried out in the UK.

Clause 21.3 of the Second 2012 Edition of the Code stated that companies must disclose details of clinical trials in accordance with the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases and the Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature.

The relevant supplementary information stated that this clause required the provision of details about ongoing clinical trials (which must be registered within 21 days of initiation of patients enrolment) and completed trials for medicines licensed for use in at least one country. Further information was to be found in the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases 2009 and the Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature 2010, both at http://www.clinicaltrials.ifpma.org.

The Panel noted that the first Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases was agreed in 2005 by the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA), the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA), the Japanese Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA) and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). The announcement was dated 6 January 2005.

The Panel noted that Article 9, Clinical Research and Transparency, of the most recent update of the IFPMA Code of Practice (which came into operation on 1 September 2012) included a statement that companies disclose clinical trial information as set out in the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases (2009) and the Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature (2010). As companies had, in effect, agreed the joint positions their inclusion in the IFPMA Code should not have made a difference in practice to IFPMA member companies but meant that IFPMA member associations had to amend their codes to reflect Article 9. The Second 2012 Edition of the ABPI Code fully reflected the requirements of the IFPMA Code. The changes introduced in the ABPI Code were to update the date of the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information and to include the new requirement to disclose in accordance with the Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results. Pharmaceutical companies that were members of national associations but not of IFPMA would have additional disclosure obligations once the national association amended its code to meet IFPMA requirements. The disclosures set out in the joint positions were not required by the EFPIA Codes.

The Panel noted that even if the UK Code did not apply many of the companies listed by the complainant were members of IFPMA and/or EFPIA.

The Panel considered that it was good practice for clinical trial results to be disclosed for medicines which were first approved and commercially available after 6 January 2005 (the date of the first joint position). This was not necessarily a requirement of the ABPI Codes from that date as set out below.

As far as the ABPI Code was concerned, the Panel noted that the first relevant mention of the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases 2005 was in the supplementary information to Clause 7.5 of the 2006 Code:

‘Clause 7.5 Data from Clinical Trials

Companies must provide substantiation following a request for it, as set out in Clause 7.5. In addition, when data from clinical trials is used companies must ensure that where necessary that data has been registered in accordance with the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases 2005.’

Clause 7.5 of the 2006 Code required that substantiation be provided at the request of health professionals or appropriate administrative staff. Substantiation of the validity of indications approved in the marketing authorization was not required. The Panel considered this was not relevant to the complaint being considered which was about disclosure of clinical trial results. The Joint Position 2005 was mentioned in the supplementary information to Clause 21.5 but this did not relate to any Code requirement to disclose clinical trial results.

In the 2008 ABPI Code (which superceded the 2006 Code and came into operation on 1 July 2008 with a transition period until 31 October 2008 for newly introduced requirements), Clause 21 referred to scientific services and Clause 21.3 stated:

‘Companies must disclose details of clinical trials.’

The relevant supplementary information stated:

‘Clause 21.3 Details of Clinical Trials

This clause requires the provision of details about ongoing clinical trials (which must be registered within 21 days of initiation of patients enrolment) and completed trials for medicines licensed for use in at least one country. Further information can be found in the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases 2005 (http:// clinicaltrials.ifpma.org).

Details about clinical trials must be limited to factual and non-promotional information. Such information must not constitute promotion to health professionals, appropriate administrative staff or the public.’

In the 2011 Code (which superceded the 2008 Code and came into operation on 1 January 2011 with a transition period until 30 April 2011 for newly introduced requirements), the supplementary information to Clause 21.3 was updated to refer to the 2008 IFPMA Joint Position.

In the Second 2012 Edition (which came into operation on 1 July 2012 with a transition period until 31 October 2012 for newly introduced requirements), changes were made to update the references to the joint position and to include the Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature. Clause 21.3 now stated:

‘Companies must disclose details of clinical trials in accordance with the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical Trial Registries and Databases and the Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature.’

The relevant supplementary information stated:

‘Clause 21.3 Details of Clinical Trials

This clause requires the provision of details about ongoing clinical trials (which must be registered within 21 days of initiation of patients enrolment) and completed trials for medicines licensed for use in at least one country. Further information can be found in the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information via Clinical

Trial Registries and Databases 2009 and the Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature 2010, both at http:// clinicaltrials.ifpma.org.

Details about clinical trials must be limited to factual and non-promotional information. Such information must not constitute promotion to health professionals, appropriate administrative staff or the public.’

The Panel noted that in the 2014 ABPI Code the disclosure requirements which had previously been stated in Clause 21 had been moved to Clause 13. In addition, the supplementary information stated that companies must include on their website information as to where details of their clinical trials could be found. The 2014 Code would come into effect on 1 May 2014 for newly introduced requirements following a transition period from 1 January 2014 until 30 April 2014.

The Panel examined the Joint Position on the Disclosure of Clinical Trial Information which was updated on 10 November 2009 and superseded the Joint Position 2008. With regard to clinical trial registries the document stated that all trials involving human subjects for Phase I and beyond at a minimum should be listed. The details should be posted no later than 21 days after the initiation of enrolment. The details should be posted on a free publicly accessible internet-based registry. Examples were given. Each trial should be given a unique identifier to assist in tracking. The Joint Position 2009 provided a list of information that should be provided and referred to the minimum Trial Registration Data Set published by the World Health Organisation (WHO). The Joint Position 2009 referred to possible competitive sensitivity in relation to certain data elements and that, in exceptional circumstances, this could delay disclosure at the latest until after the medicinal product was first approved in any country for the indication being studied. Examples were given.

The Panel noted that the complaint related to the disclosure of clinical trial results.

With regard to the disclosure of clinical trial results the Joint Position 2009 stated that the results for a medicine that had been approved for marketing and was commercially available in at least one country should be publicly disclosed. The results should be posted no later than one year after the medicine was first approved and commercially available. The results for trials completed after approval should be posted one year after trial completion – an adjustment to this schedule was possible to comply with national laws or regulations or to avoid compromising publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

The Joint Position 2009 included a section on implementation dates and the need for companies to establish a verification process.

The Joint Position 2005 stated that the results should be disclosed of all clinical trials other than exploratory trials conducted on a medicine that was approved for marketing and was commercially available in at least one country. The results generally should be posted within one year after the medicine was first approved and commercially available unless such posting would compromise publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal or contravene national laws or regulations. The Joint Position 2008 was dated 18 November 2008 and stated that it superseded the Joint Position 2005 (6 January and 5 September). The Joint Position 2008 stated that results should be posted no later than one year after the product was first approved and commercially available in any country. For trials completed after initial approval these results should be posted no later than one year after trial completion. These schedules would be subject to adjustment to comply with national laws or regulations or to avoid compromising publication in a peer reviewed medical journal.

The Joint Position on the Publication of Clinical Trial Results in the Scientific Literature was announced on 10 June 2010. It stated that all industry sponsored clinical trials should be considered for publication and at a minimum results from all Phase III clinical trials and any clinical trials results of significant medical importance should be submitted for publication. The results of completed trials should be submitted for publication wherever possible within 12 months and no later than 18 months of the completion of clinical trials for already marketed medicines and in the case of investigational medicines the regulatory approval of the new medicine or the decision to discontinue development.

Having examined the various codes and joint positions, the Panel noted that the Joint Position 2005 excluded any clinical trials completed before 6 January 2005. The position changed on 18 November 2008 as the Joint Position 2008 did not have any exclusion relating solely to the date the trial completed. The Joint Position 2009 was similar to the Joint Position 2008 in this regard.

The Panel noted that deciding which Code applied, and thus which joint position, was complicated. It noted that the 2011 Code which, taking account the transition period, came into operation on 1 May 2011 was the first edition of the Code to refer to the Joint Position 2008.

The Panel concluded that from 1 November 2008, (allowing for the transition period) until 30 April 2011 under the 2008 Code companies were required to follow the Joint Position 2005. From 1 May 2011 until 31 October 2012 under the 2012 Code companies were required to follow the Joint Position 2008. Since 1 November 2012 companies were required to follow the Joint Position 2009. The Panel considered that since the 2008 Code companies were, in effect, required to comply with the Joint Position cited in the relevant supplementary information. The relevant supplementary information gave details of what was meant by Clause 21.3 (Clause 13.1 in the 2014 Code). The Panel accepted that the position was clearer in the Second 2012 Edition of the Code. The Panel noted that the 2011 Code should have been updated to refer to the Joint Position 2009.

For medicines first licensed and commercially available in any country from 1 November 2008 until 30 April 2011 the results of clinical trials completed before 6 January 2005 would not have to be posted.

From 1 May 2011 there was no exclusion of trials based solely on completion date and so for a product first licensed and commercially available anywhere in the world after 1 May 2011 the applicable joint positions required relevant clinical trial results to be posted within a year of the product being first approved and commercially available or within a year of trial completion for trials completed after the medicine was first available.

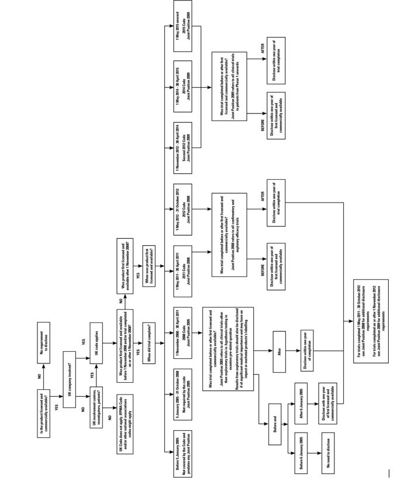

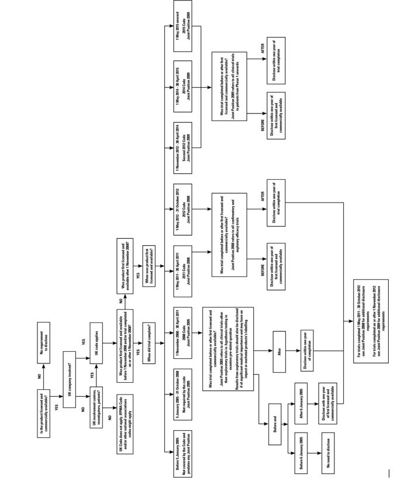

Noting that the complaint concerned licensed products the Panel considered that the trigger for disclosure was the date the product was first approved and commercially available anywhere in the world. This would determine which version of the Code (and joint position) applied for trials completed prior to first approval. The next consideration was whether the trial completed before or after this date. For trials completing after the date of first approval, the completion date of the trial would determine which Code applied. The Panel considered that the joint positions encouraged disclosure as soon as possible and by no later than 1 year after first availability or trial completion as explained above. The Panel thus considered that its approach was a fair one. In this regard, it noted that the complaint was about whether or not trial results had been disclosed, all the joint positions referred to disclosure within a one year timeframe and companies needed time to prepare for disclosure of results. The Panel considered that the position concerning unlicensed indications or presentations of otherwise licensed medicines etc would have to be considered on a case by case basis bearing in mind the requirements of the relevant joint position and the legitimate need for companies to protect intellectual property rights. The Panel followed the decision tree set out below which it considered set out all the relevant possibilities.

During its development of the decision tree, the Panel sought advice from Paul Woods, BPharm MA (Medical Ethics and Law) of Paul Woods Compliance Ltd who provided an opinion. Mr Woods was not provided with details of the complaint or any of the responses. The advice sought was only in relation to the codes and joint positions.

The Panel considered the complaint could be read in two ways: firstly that the companies listed had not disclosed the data referred to in the CMRO publication relating to the products named or secondly, more broadly, that the companies had not disclosed the clinical trial data for the product named ie there could be studies in addition to those looked at in the CMRO publication. The Panel decided that it would consider these cases in relation to the studies covered by the CMRO publication and not on the broader interpretation. Companies would be well advised to ensure that all the clinical trial results were disclosed as required by the Codes and joint positions. The Panel considered that there was no complaint about whether the results disclosed met the requirements of the joint positions so this was not considered. In the Panel’s view the complaint was only about whether or not study results had been disclosed and the timeframe for such disclosure.

The CMRO publication stated that as far as the IFPMA Joint Position was concerned implementation had been somewhat variable in terms of completeness and timing. The Panel noted that a number of studies were referred to in the CMRO publication as ‘unevaluable’ and these were not specifically mentioned by the complainant. The CMRO publication focussed on the disclosure of evaluable trial results and the Panel only considered those evaluable trials.

Decision Tree - Developed by the Panel when considering the complaint about the disclosure of clinical trial results (for enlarged version see pdf of case report)

The Panel noted that its consideration of these cases relied upon the information provided by the respondent companies. The CMRO publication did not identify the studies evaluated; it only provided quantitative data. The Panel noted that the study ran from 27 December 2012 to 31 January 2013 and was published in November 2013. The Panel considered that companies that might not have been in line with various disclosure requirements had had a significant period of time after the study completed and prior to the current complaint being received to have disclosed any missing information. It appeared that the authors of the CMRO publication had contacted various companies for additional information.

The Panel noted that the case preparation manager raised Clause 1.8 of the Second 2012 Edition with the companies. The supplementary information to

Clause 1.8, Applicability of Codes, inter alia, referred to the situation when activities involved more than one country or where a pharmaceutical company based in one country was involved in activities in another country. The complainant had not cited Clause 1.8. The Panel noted that any company in breach of any applicable codes, laws or regulations would defacto also be in breach of Clause 1.8 of the Code; the converse was true. The Panel thus decided that as far as this complaint was concerned, any consideration of a breach or otherwise of Clause 1.8 was covered by other rulings and it decided, therefore, not to make any ruling regarding this clause (or its equivalent in earlier versions of the Code).

PANEL RULING IN CASE AUTH/2671/11/13

The Panel noted the CMRO publication in that twelve evaluable studies had not been disclosed within the timeframe. The disclosure percentage was 63%. Six studies completed before the end of 2012 had not been disclosed. The disclosure percentage at 31 January 2013 of trials completed before the end of January 2012 was 83%. A footnote stated that the undisclosed trials were in the process of being prepared for publication.

The Panel noted that Valdoxan was approved for use in Europe in February 2009. In response to a question whether this was when the product was first approved and commercially available anywhere in the world. Servier stated that the relevant date was March 2009. [See post consideration note].

The Panel was only concerned with studies which involved UK patients or involved the UK company. Two studies (25 and 26) which completed in September 2008 and April 2009 had, according to Servier, not been disclosed within the timeframe. The Panel did not agree with Servier’s submission that these studies had been disclosed very promptly thereafter. It appeared from the information provided by Servier that the abstracts for the studies were published in June 2010 and March 2011 with publication in 2011 and 2013 respectively.

The Panel noted that the relevant Code was 2008 and the Joint Position 2005. Servier should have disclosed the results for one study (Study 25) by March 2010 and the other study (Study 26) by April 2010. As the results were not disclosed within this timeframe Servier had not met the requirements of the Code. The Panel ruled a breach of Clause 21.3 of the 2008 Code as acknowledged by Servier. The Panel agreed with Servier that not every breach of Clause 21.3 would necessarily be a breach of other clauses of the Code, in particular Clauses 9.1 and 2. However, it considered that the delay in disclosure meant that high standards had not been maintained. A breach of Clause 9.1 was ruled. As the results had been disclosed the Panel considered that on balance there was no breach of Clause 2 and ruled accordingly.

The results of a further three studies (29, 30 and 31) which involved UK patients and completed in September 2011, August 2011 and December 2008 were still to be disclosed. The Panel considered that Servier, by not disclosing the results within 12 months of study completion (Study 30) or by one year after first approval (Study 31) ie by August 2012 and March 2010 respectively, the company had not met the requirements of the Code. The Panel ruled a breach of Clause 21.3 of the 2011 Code in relation to the study which completed in August 2011 (Study 30). The study which completed in December 2008 (Study 31) was ruled in breach of Clause 21.3 of the 2008 Code.

Study 29 completed in September 2011 and was carried out on a different formulation. The relevant Code was the 2011 Code and thus the Joint Position 2008 which stated that if trial results for an investigational product that had failed in development had significant medical importance, study sponsors were encouraged to post the results. The Panel was unsure whether the product had ‘failed in development’ or whether the results were of significant medical importance. Further companies were only encouraged to post results if possible. The complainant had not provided any details in this regard. The Panel considered that publication of such data was preferable, however failure to publish was not necessarily out of line with the Joint Position 2008. Thus the Panel ruled no breach of Clause 21.3 of the 2011 Code and consequently no breach of Clause 9.1 and 2.

The Panel noted that it now had to consider Clauses 9.1 and 2 with regard to Studies 30 and 31. It noted that the wording of Clauses 9.1 and 2 was the same in the 2008 Code as in the 2011 Code. The Panel noted that Servier knew from the CMRO publication that some of its trial data results had not been disclosed. The ABPI study was conducted between December 2012 and January 2013 but in the 9½ months that had elapsed between the end of the study and the receipt of this complaint, the company had not subsequently disclosed the missing data. Not withstanding the company’s submission that the missing data was being prepared for publication, the Panel considered that failure to disclose the data meant that high standards had not been maintained and a breach of Clause 9.1 was ruled.

The Panel also considered that failure to disclose meant that Servier had brought discredit upon, and reduced confidence in, the pharmaceutical industry and a breach of Clause 2 was ruled.

The Panel noted there was no way of identifying from the list of 49 studies provided by Servier which were the remaining seven studies cited in the CMRO publication. If these studies had no UK involvement the matter did not come within the scope of the UK Code. If these studies had UK involvement but were completed before 5 January 2006 they would be exempted under the 2005 Joint Position. The Panel noted that the results from all studies, apart from the three (29, 30, 31) considered above, had been disclosed. The Panel noted its dilemma and decided that the studies with no UK involvement did not come within the scope of the UK Code and therefore ruled no breach. The results of studies that completed before 5 January 2005 did not need to be disclosed. Thus the Panel ruled no breach of Clause 21.3 of the 2008 Code and consequently no breach of Clauses 9.1 and 2.

[Post consideration note: Following notification of the Panel’s rulings, Servier pointed out that Valdoxan was first approved and commercially available in the Ukraine in February 2007. The date of March 2009 related to its availability in the European Union. Servier decided not to appeal the Panel’s rulings of breaches of Clauses 9.1 and 21.3 of the 2008 Code in relation to Study 25].

Complaint received 21 November 2013

Case completed 11 April 2014

see cases: 3005,2908,2906,2903,2898,2763,2676,2674,2673,2672,2671,2670,2669,2667,2666,2665,2664,

2663,2662,2661,2659,2657,2654