CASE AUTH/2607/5/13 PFIZER v GLAXOSMITHKLINE GSK

NO BREACH OF THE CODE

Votrient leavepiece

Pfizer complained about a Votrient (pazopanib) GlaxoSmithKline leavepiece entitled ‘New data – COMPARZ study’ (COMParing the efficacy, sAfety and toleRability of paZopanib vs sunitinib in first-line advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma). The leavepiece also referred to the PISCES study (Patient preference between pazopanib and sunitinib: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma).

Votrient was indicated, inter alia, in adults for the first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and for patients who had received prior cytokine therapy for advanced disease. Pfizer marketed sunitinib (Sutent).

The detailed response from GlaxoSmithKline is given below.

Pfizer noted that the COMPARZ study was a head-to-head, non-inferiority study, to investigate the relative efficacy of sunitinib and pazopanib for the treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer. The protocol-defined criterion for non-inferiority was that the hazard ratio for progression-free survival would be contained within the upper bound of a two-sided 95% CI of 1.25 (subsequently tightened to 1.22 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA)). Submission of the COMPARZ results to the EMA was a post authorization measure for the conditional marketing authorization.

Pfizer noted that the leavepiece presented several analyses of data and it was claimed that pazopanib was non-inferior to sunitinib in terms of progression-free survival. It was not clear that the intention-to-treat (ITT) population was used to provide the progression-free survival comparison.

Pfizer noted that whilst the ITT population met the pre-defined criteria for non-inferiority, the per protocol (PP) analysis did not. The ITT analysis was an unusual and importantly non-conservative choice for a non-inferiority study. Pfizer referred to international and expert group guidance from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the EMA and submitted that the PP analysis was critical for clinicians to judge the totality of the data and make informed treatment decisions regarding these two medicines. Pfizer alleged that to present only the ITT analysis in the leavepiece but not label it as such was misleading; both the ITT analysis and the PP analysis should be presented in all promotional materials.

Importantly, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) had recently recommended that, on the basis of all of the data, including the COMPARZ study, that pazopanib be granted a normal licence. This made it even more critical that the COMPARZ data was presented transparently and ethically so that clinicians could make an informed treatment decision based on a good understanding of the relative efficacy of each medicine.

The Panel noted that the primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study was progression-free survival assessed by independent review, to be performed on the ITT population. In that regard the Panel noted the submissions about the relative merits of ITT vs PP analyses in non-inferiority studies and that both were associated with differing strengths and weaknesses. Statistical guidance did not prohibit the use of an ITT analysis in non-inferiority studies. The EMA appeared to consider that the ITT analysis and the PP analysis were equally important and that their use should lead to similar conclusions for a robust interpretation of the result.

The Panel noted that the COMPARZ study had been designed such that the primary analysis would be conducted on the ITT population; progression free survival would be assessed by independent reviewers. The CHMP, amongst others, had accepted that this design was appropriate. The Panel noted GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that the proposed study analysis plan had been reviewed by the CHMP and that although it had requested a tighter non-inferiority margin of 1.22 vs 1.25, it had not raised any concerns about the use of ITT as the primary analysis population. The Panel noted that in a sensitivity analysis on the PP population, the hazard ratios were very similar to those from the ITT analysis with confidence intervals that overlapped (PP analysis 0.910 – 1.255 vs ITT analysis 0.8982 – 1.2195). The Panel thus considered that the results of the PP analysis and the ITT analysis appeared to be consistent. The primary ITT analysis met the CHMP defined primary endpoint of an upper bound of no more than 1.22 and thus demonstrated noninferiority between Votrient and sunitinib. The Panel noted that when progression-free survival was assessed by investigators the confidence interval was 0.863 – 1.154 which also satisfied the CHMP limits.

The Panel noted that the COMPARZ study objectives were set out on page 3 of the leavepiece and the primary endpoint was stated ie to evaluate noninferiority in progression-free survival between Votrient and sunitinib. It was not stated that that analysis would be in the ITT population. A diagram depicted the patient numbers in each treatment arm ie Votrient n=557 and sunitinib n=553. Patients randomized into a trial formed, by definition, the ITT population Although the graphs on page 4 headed ‘Primary Endpoint – PFS (independent review)’ and ‘Progression Free Survival (investigator review)’ respectively did not state that the analysis was performed on the ITT population, a table embedded into the two graphs noted the patients numbers in each treatment arm (ie Votrient n=557 and sunitinib n=553). In that regard the Panel considered that, although not specifically stated on page 4, readers could deduce, given the information on page 3, that the primary endpoint analysis was carried out on the ITT population. The Panel noted its comments above about the satisfaction of the CHMP primary endpoint. The Panel considered that although it would have been helpful to explicitly refer to the ITT population on page 4, on balance the failure to do so was not misleading. No breach of the Code was ruled.

The Panel considered that as the primary ITT analysis and the PP analysis were so similar, it was not misleading to refer only to the ITT analysis. No breach of the Code was ruled.

The Panel considered that the claims regarding the non-inferiority of Votrient vs sunitinib could be substantiated. No breach of the Code was ruled.

Upon appeal by Pfizer the Appeal Board noted that the primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study was met in that Votrient was shown to be non-inferior to sunitinib with respect to progression-free survival assessed by independent reviews performed on the ITT population.

The Appeal Board considered that as the graphs on page 4 included the same patient numbers as stated on page 3, it could be concluded that this was the ITT population and analysis. The Appeal Board noted that an ITT analysis more closely reflected clinical practice.

The Appeal Board noted the conflicting academic debate on the merits of ITT vs PP analysis. The Appeal Board noted that a sensitivity analysis of the PP population had been included in the COMPARZ study and that hazard ratios from that analysis were very similar to those from the ITT analysis with overlapping confidence intervals. The Appeal Board considered that the differences between the ITT and PP results were unlikely to translate as a meaningful difference to an individual patient. It appeared that the ITT and PP results were not inconsistent.

The Appeal Board noted that the CHMP had accepted that the design of the COMPARZ study was appropriate (subject to a tighter non-inferiority margin of 1.22) in that the primary endpoint was based upon the ITT analysis. The Appeal Board also noted that the COMPARZ study had been published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Whilst it might have been helpful to label the ITT analysis, the Appeal Board noted its comments above and considered that Pfizer had not established that the failure to do so was misleading. The Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of no breaches of the Code. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

The Appeal Board noted its comments above and considered that it was not misleading to refer only to the ITT analysis. The Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of no breaches of the Code. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

The Appeal Board considered that claims regarding the non-inferiority of Votrient vs sunitinib could be substantiated and upheld the Panel’s ruling of no breach of the Code. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

With regards to the claim on page 10 that ‘COMPARZ complements the PISCES study which demonstrated patient preference for Votrient’, Pfizer stated that the PISCES study was a two stage, randomized, cross-over study where patients received one cycle of each medicine (sunitinib and pazopanib) in turn, separated by a washout period. At the end of the study period, patients were asked which they would prefer to take assuming that both medicines were equally efficacious.

Pfizer stated that as non-inferiority trials could not prove equal efficacy, no claims about patient preference could be made for pazopanib because such claims would be based on a false assumption and would be misleading.

The Panel noted that the PISCES study looked at whether patients preferred Votrient, sunitinib or had no preference for either. In the Panel’s view, patients had to enter such a study on the premise that the two medicines in question had equal efficacy. The Panel noted that in small print at the bottom of page 10, it was stated that patients were asked ‘Now that you have completed both treatments, which of the two drugs would you prefer to continue to take as the treatment for your cancer, assuming that both will work equally well in treating your cancer?’ The Panel did not consider that readers would view this explanation as a claim that Votrient and sunitinib had equivalent efficacy. Given the outcome of COMPARZ, a patient preference study based on the question above was not unreasonable; patients would not understand the question if they were asked to assume that the two medicines were non-inferior. In the Panel’s view the claim at issue was not misleading as alleged and could be substantiated. No breach of the Code was ruled.

Upon appeal by Pfizer the Appeal Board considered that in order to determine preference it was acceptable that participants were first asked ‘Now that you have completed both treatments, which of the two drugs would you prefer to continue to take as the treatment for your cancer, assuming that both drugs will work equally well in treating your cancer?’. The Appeal Board noted that COMPARZ had shown that pazopanib was non-inferior to sunitinib. Patients would understand the phrase ‘work equally well’ far more easily than the phrase ‘non-inferior’. The Appeal Board noted that at the appeal hearing Pfizer agreed that the PISCES study design was appropriate.

The Appeal Board did not consider that the fact that the patient question appeared in small print at the bottom of the page and was linked to the claim ‘COMPARZ complements the PISCES study which demonstrated patient preference for Votrient’ implied that Votrient and sunitinib had equal efficacy. The patient question helped place the study in context. The claim was not misleading and could be substantiated. The Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of no breaches of the Code. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

Pfizer stated that the way that the data had been presented in the detail aid did not provide all of the evidence that clinicians required to make a decision about the relative merits of pazopanib and sunitinib. Pfizer noted that in the detail aid and at a major congress, GlaxoSmithKline had presented only the analysis where the endpoint of non-inferiority was met and had only published the PP analysis on its website. Pfizer alleged that this was a deliberate attempt to mislead, in breach of Clause 2.

The Panel noted its rulings above of no breach of the Code and consequently ruled no breach of Clause 2 of the Code which was upheld on appeal by Pfizer. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

Pfizer Limited complained about a Votrient (pazopanib) leavepiece (ref (UK/PAZ/0332/12) issued by GlaxoSmithKline UK Ltd, entitled ‘New data – COMPARZ study’ (COMParing the efficacy, sAfety and toleRability of paZopanib vs sunitinib in first-line advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma). The leavepiece also referred to the PISCES study (Patient preference between pazopanib and sunitinib: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma).

Votrient was indicated, inter alia, in adults for the first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma and for patients who had received prior cytokine therapy for advanced disease. Pfizer marketed sunitinib (Sutent).

GlaxoSmithKline explained that there were six medicines licensed to treat advanced renal cell cancer in treatment-naive patients. The two medicines which had positive National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for first-line use were pazopanib and sunitinib both of which were tyrosine kinase inhibitors and licensed to treat advanced and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clinicians and patients increasingly looked to understand how these medicines compared with one another in terms of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Unfortunately this desire had been frustrated by a lack of head-to-head data.

GlaxoSmithKline undertook the COMPARZ and PISCES studies to provide clinicians and patients with robust data which directly compared pazopanib and sunitinib. The COMPARZ study focussed primarily on efficacy and assessed whether pazopanib was non-inferior to sunitinib in terms of progression-free survival (PFS). The PISCES study was an innovative study in the field of advanced renal cell cancer, designed to assess patient preference between the two medicines ie based on their experience of taking both, patients were asked if they preferred one or the other or neither. Since neither medicine was curative, patient preference was a particularly important consideration in advanced cancer.

GlaxoSmithKline stated that in its view these studies complemented one another. They addressed two different but important considerations which clinicians and patients would want to take into account when choosing between pazopanib and sunitinib for treating advanced renal cell cancer.

1 COMPARZ endpoint data

COMPLAINT

Pfizer noted that the COMPARZ study was a headto-head, non-inferiority study, to investigate the relative efficacy of sunitinib and pazopanib for the treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer. The protocol-defined criterion for non-inferiority was that the hazard ratio for progression-free survival would be contained within the upper bound of a two-sided 95% CI of 1.25. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) subsequently required a tighter definition; the upper bound of a two-sided 95% CI of 1.22. Submission of results from the COMPARZ study to the EMA was a post authorization measure for the conditional marketing authorization as outlined in Annex II C ‘Specific obligations to complete postauthorization measures for the conditional marketing authorization’.

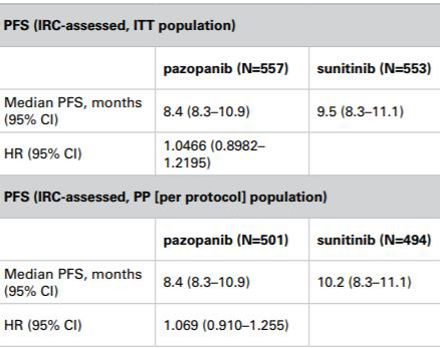

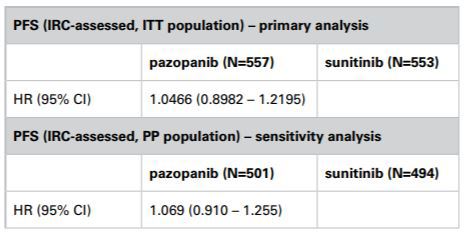

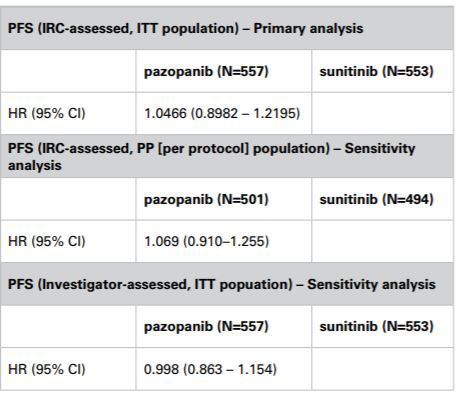

Pfizer noted that on page 4 of the leavepiece, several analyses of data were presented and it was claimed on page 10 and elsewhere that pazopanib was non-inferior to sunitinib in terms of progressionfree survival. Pfizer was concerned about the data presented in the leavepiece to evidence this claim. It was not clear from page 4 what analysis set was used to provide the progression-free survival comparison, nor was it clear from the study schema on page 3. It was apparent from a clinical study report published on GlaxoSmithKline’s website and from inter-company dialogue that the intention-to-treat (ITT) population was presented here. The clinical study report provided the following results for the trial:

Whilst the ITT population met the pre-defined criteria for non-inferiority, the per protocol (PP) analysis did not. Pfizer submitted that the ITT analysis would be an unusual and importantly non-conservative choice for a non-inferiority study. Major international guidance stated the following:

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Draft FDA Guidance for industry, Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials 2010:

‘Good Study Quality A variety of study quality deficiencies can introduce what is known as a “bias toward the null,” where the observed treatment difference in an NI study is decreased from the true difference between treatments. These deficiencies include imprecise or poorly implemented entry criteria, poor compliance, and use of concomitant treatments whose effects may overlap with the drugs under study, inadequate measurement techniques, or errors in delivering assigned treatments. Many such defects have small (or no) effects on the variability of outcomes (variance) but reduce the observed difference C-T, potentially leading to a false conclusion of non-inferiority. It should also be appreciated that intent-to-treat approaches, which preserve the principle that all patients are analyzed according to the treatment to which they have been randomized even if they do not receive it, although conservative in superiority trials, are not conservative in an NI study, and can contribute to this bias toward the null.’ EMA, ICHE9:

‘5.2.3 Roles of the Different Analysis Sets

In general, it is advantageous to demonstrate a lack of sensitivity of the principal trial results to alternative choices of the set of subjects analysed. In confirmatory trials it is usually appropriate to plan to conduct both an analysis of the full analysis set and a per protocol analysis, so that any differences between them can be the subject of explicit discussion and interpretation. In some cases, it may be desirable to plan further exploration of the sensitivity of conclusions to the choice of the set of subjects analysed. When the full analysis set and the per protocol set lead to essentially the same conclusions, confidence in the trial results is increased, bearing in mind, however, that the need to exclude a substantial proportion of subjects from the per protocol analysis throws some doubt on the overall validity of the trial.

The full analysis set and the per protocol set play different roles in superiority trials (which seek to show the investigational product to be superior), and in equivalence or non-inferiority trials (which seek to show the investigational product to be comparable, see section 3.3.2). In superiority trials the full analysis set is used in the primary analysis (apart from exceptional circumstances) because it tends to avoid over-optimistic estimates of efficacy resulting from a per protocol analysis, since the non-compliers included in the full analysis set will generally diminish the estimated treatment effect. However, in an equivalence or non-inferiority trial use of the full analysis set is generally not conservative and its role should be considered very carefully.’

EMA points to consider on switching between non-inferiority and superiority:

‘In a non-inferiority trial, the full analysis set and the PP analysis set have equal importance and their use should lead to similar conclusions for a robust interpretation.’

CONSORT statement:

‘In non-inferiority and equivalence trials, nonITT analyses might be desirable as a protection from ITT’s increase of type I error risk (falsely concluding non-inferiority). There is greater confidence in results when the conclusions are consistent.’

The CONSORT statement further advised that when data was presented or published:

‘It should be indicated whether the conclusion relating to non-inferiority or equivalence is based on ITT or per protocol analysis or both and whether those conclusions are stable with respect to different types of analyses (eg, ITT, per-protocol). Conclusions should preferably be stated in terms of the prespecified non-inferiority or equivalence margin using language consistent with the aim of the trial.’

It was clear, then, that the PP analysis was critical in allowing clinicians to judge the totality of the data and allow them to make informed treatment decisions regarding these two medicines. Pfizer considered that to present only the ITT analysis in the leavepiece but not label it as such was misleading; both the ITT analysis and the PP analysis should be presented in all promotional materials.

Importantly, the CHMP had recently recommended that, on the basis of the totality of data presented to it, including the COMPARZ study, that pazopanib be granted a normal licence. This made it even more critical that the data from COMPARZ were presented transparently and ethically to allow clinicians to make an informed treatment decision based on a good understanding of the relative efficacy of each medicine.

Pfizer alleged breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.3, 7.4 and 7.8.

RESPONSE

GlaxoSmithKline stated that COMPARZ was a randomised, open-label, head-to-head, noninferiority study designed to evaluate PFS with pazopanib vs sunitinib. The primary analysis prespecified in the COMPARZ protocol was PFS as assessed by independent review, to be performed on the ITT population. The study was powered to detect non-inferiority in terms of PFS between pazopanib and sunitinib. The protocol-defined criterion for non-inferiority was that the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for the point estimate of the hazard ratio must be less than 1.25. As noted by Pfizer, this study was conducted, in part, to meet EMA requirements. GlaxoSmithKline noted that the EMA reviewed the design of COMPARZ and required a stricter criterion for establishing non-inferiority; insisting that the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for the point estimate of the hazard ratio did not exceed 1.22.

Results relating to the primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study were clearly and prominently presented on page 4 of the leavepiece. Since the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval fell below the pre-specified non-inferiority margin (both the 1.25 margin defined in the protocol, and the stricter 1.22 margin required by the EMA) the study unequivocally met its primary endpoint and demonstrated noninferiority of pazopanib to sunitinib. GlaxoSmithKline stated that it could thus claim that the COMPARZ study demonstrated that pazopanib was non-inferior to sunitinib in terms of PFS. The CHMP, the committee of the EMA which had reviewed this data, reached the same conclusion and stated that ‘Based on the VEG108844 (COMPARZ) study and the fulfilment of the pre-set non-inferiority margin of HR 1.22, pazopanib is considered non-inferior to sunitinib with regard to PFS and OS’.

As a result of the COMPARZ study the CHMP recommended that the conditional marketing authorization granted to pazopanib be converted to a full marketing authorization. Furthermore, a paper which detailed the design, results and conclusion of the COMPARZ study had been accepted for publication by a major international peer reviewed journal. This clearly indicated that the peer review panel considered that the study was methodologically valid.

GlaxoSmithKline noted that whilst Pfizer was concerned about how the claim (that pazopanib was non-inferior to sunitinib in terms of PFS) was evidenced in the leavepiece, it had agreed in a teleconference with GlaxoSmithKline (Wednesday, 8 March) that the study met its pre-defined primary endpoint of non-inferiority for pazopanib compared with sunitinib based on the ITT analysis.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer’s statement that ‘for a non-inferiority study, the ITT analysis would be an unusual and importantly non-conservative choice’ was factually incorrect and not supported by regulatory guidance or current statistical thinking. The debate on the relative merits of an ITT vs PP analysis remained on-going amongst academic statisticians, exemplified by the fact that the FDA guidance cited by Pfizer was distributed in March 2010 for comment purposes only and remained in draft format. The EMA guidance did not conclude that both ITT and PP analyses must meet a pre-defined non-inferiority margin, rather that they should lead to similar conclusions. GlaxoSmithKline believed this was the case with respect to the COMPARZ study, and this opinion was clearly supported by both the CHMP and the panel of journal peer reviewers.

Undertaking PP analyses had its own set of pitfalls and should not be considered a more reliably conservative choice. In particular:

- ‘... the corresponding test [on the per protocol set] of the hypothesis and estimate of the treatment effect may or may not be conservative depending on the trial; bias, which may be severe, arises from the fact that adherence to the study protocol may be related to treatment and outcome.’ (Regulatory guidance 1998)

- ‘Unfortunately it is possible to envisage circumstances under which the exclusion of patients in a per protocol analysis might bias the results towards a conclusion of no difference – for example, if patients not responding to one of the two treatments dropped out early.’ (Jones et al 1996)

- There was no universally agreed definition of what would constitute a PP population in an oncology trial. The PP analysis set was defined differently for different studies. As the study sponsor defined the criteria for exclusion, this in itself could introduce the question of bias. By comparison, there was a very clear and widely accepted definition for the ITT population.

- Two meta-analyses have compared the results of PP and ITT analyses. Both showed results that contradict Pfizer’s claim that PP analysis was, by default, more conservative (Ebbutt and Firth 1998 and Brittain and Lin 2005).

GlaxoSmithKline considered that it was appropriate to base the primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study on the ITT population. Moreover, regulatory agencies, the trial steering committee which included a range of relevant independent international experts, ethics committees and the data safety monitoring board all considered that the study design was appropriate. Importantly, since the study was conducted, in part, to meet specific regulatory obligations, the CHMP, a committee of the EMA, reviewed the proposed study analysis plan in detail and requested the tighter non-inferiority margin of 1.22 but did not raise any concerns about the use of ITT as the primary analysis population.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that as with most clinical trials, various sensitivity analyses were planned including one which assessed efficacy based on the PP population. A PP analysis excluded major protocol deviators and therefore, compared with the corresponding ITT analysis, invariably left fewer subjects available for analysis which resulted in a reduction in power and consequently wider confidence intervals.

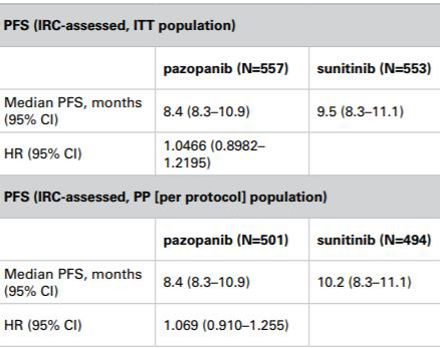

The results obtained from the PP sensitivity analysis of COMPARZ were in line with those from the primary (ITT) analysis (table below). In particular, hazard ratios obtained from the PP analysis were similar to those from the ITT analysis with substantially overlapping confidence intervals. Predictably, the PP analysis included fewer subjects than the ITT analysis which resulted in a wider confidence interval.

Summary of relevant results from the COMPARZ study

GlaxoSmithKline considered that Pfizer’s statement that ‘while the ITT population met the pre-defined criteria for non-inferiority, the per protocol analysis did not’ was highly misleading. The non-inferiority margin was pre-defined purely in relation to the primary analysis (ITT) population and was never intended to be applied to the PP analysis. The study was therefore powered based on the primary (ITT) analysis. Had it been intended that the predefined criteria for non-inferiority be applied to the PP analysis, a larger sample size would have been required at the outset to take into account subjects who deviated from the protocol and were therefore not included in the PP analysis.

GlaxoSmithKline noted Pfizer’s allegation that it was misleading to only present the ITT analysis but not label it as such and that both the ITT and the PP analysis should be presented in all materials.

In terms of only presenting the primary ITT analysis in the leavepiece, GlaxoSmithKline considered that this approach was acceptable and in line with usual practice. Inevitably, a leavepiece could only provide a summary of the enormous volume of data and analysis about a particular medicine. GlaxoSmithKline took great care to ensure that marketing materials presented information about a medicine in a fair and balanced way. Where marketing material was focussed on a particular clinical trial, this was typically achieved by:

- clearly describing the objectives and outlining the design of the trial

- prominently displaying the results of the primary endpoint, making it clear whether or not this has been met

- including a selection of the secondary endpoints likely to be of greatest interest to prescribers

- summarising safety considerations including both commonly experienced and particularly serious adverse events associated with the medicine.

In this case, GlaxoSmithKline did not consider it necessary to include the PP sensitivity analysis and the primary endpoint ie ITT analysis. There was general agreement that COMPARZ met its primary endpoint. GlaxoSmithKline along with the CHMP and a journal peer review panel had concluded that by meeting its primary endpoint, COMPARZ had demonstrated that pazopanib was non-inferior to sunitinib in terms of PFS. As the hazard ratios obtained from the sensitivity analysis were in line with those from the primary ITT analysis, GlaxoSmithKline considered that including this analysis would add little to the reader’s understanding of the comparative efficacy of pazopanib and sunitinib.

GlaxoSmithKline did not consider that Pfizer’s reference to the recommendations contained in the CONSORT statement was relevant to the leavepiece in question. The CONSORT group recommendations pertained to transparent reporting of trials and were designed to aid authors in the preparation of articles intended for publication. Reports of clinical trials published in academic journals typically contained much greater detail than was usual in leavepieces and the like. GlaxoSmithKline considered that marketing materials should be judged against the requirements of the Code rather than the CONSORT guidance.

GlaxoSmithKline noted that additional data on the COMPARZ study was available on its website and included the PP sensitivity analysis along with other detailed analyses. It was standard practice for the company website to contain more detailed analyses of clinical trial results than would normally appear in a leavepiece. Furthermore, GlaxoSmithKline confirmed that the paper which had been accepted for publication discussed both the primary ITT efficacy analysis and the corresponding PP sensitivity analysis.

GlaxoSmithKline acknowledged that it was not stated that the primary efficacy analysis shown in the leavepiece was based on the ITT population. However, since ITT was a very common way of analysing data from clinical trials and this analysis was clearly presented as being the prespecified primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study, GlaxoSmithKline strongly refuted any suggestion that it had misled clinicians by not labelling this analysis ‘primary analysis based on ITT population’.

GlaxoSmithKline also noted that it was not unusual for materials which summarised particular studies, including leavepieces, detail aids, slide decks etc, not to state in detail exactly how particular endpoints had been analysed. For example, the RECORD-3 trial, a non-inferiority study which aimed to identify the best order in which to sequence treatment with everolimus and sunitinib in metastatic renal cell cancer, was recently presented as an oral abstract at the 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting; the analysis population was not stated in either the written abstract or during the oral presentation. Furthermore, there were examples of documents approved by the FDA and EMA wherein data from a non-inferiority study was presented from an ITT analysis and not explicitly labelled as such.

In summary, GlaxoSmithKline considered that the COMPARZ study was appropriately designed to assess the non-inferiority of pazopanib compared with sunitinib and that an entirely acceptable primary endpoint, based on analysis of the ITT population, was selected and accepted by regulatory authorities. The results of the study showed unequivocally that this endpoint was met. This view had clearly been supported by regulatory agencies and a journal peer review panel. On the basis of the COMPARZ study results, the CHMP had stated ‘pazopanib is considered non-inferior to sunitinib with regard to PFS and OS’ and, as a consequence, that ‘The marketing authorization should no longer be subject to specific obligations’.

GlaxoSmithKline considered that the leavepiece presented a fair and balanced summary of the trial design and results of the COMPARZ study, in accordance with the Code. In particular, GlaxoSmithKline did not consider that the leavepiece was misleading because the PP sensitivity analysis had not been included. In line with usual practice, the leavepiece prominently featured the primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study, included a fair and balanced selection of secondary analyses that provided prescribers with further useful information and adequately covered safety matters related to the prescription of pazopanib. It was not considered necessary to include the sensitivity analysis of efficacy based on the PP population since the results of this analysis were consistent with those of the primary (ITT) analysis.

GlaxoSmithKline thus denied breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.3, 7.4 and 7.8.

In response to a request from the Panel for further information, GlaxoSmithKline submitted that in order to appropriately contextualise its response, it was important to reiterate the substance of Pfizer’s complaint. Pfizer’s concern arose from the fact that firstly, it was not stated in the leavepiece that the primary analysis was performed on the ITT population and secondly the leavepiece did not include a sensitivity analysis based on the PP population. GlaxoSmithKline disagreed that this breached the Code for the reasons stated above and it considered that current academic and regulatory opinion supported its approach.

Pfizer had verbally agreed that the COMPARZ study had met the protocol-defined primary endpoint demonstrating non-inferiority on ITT analysis. This was supported by both an opinion issued by the CHMP on 21 March 2013 and a peer review panel who had reviewed the COMPARZ manuscript on behalf of a leading international medical journal.

GlaxoSmithKline noted that Pfizer’s concerns related to the way in which the results of the study had been presented in the leavepiece; the company had not raised any concerns about the power of the study and it therefore queried the Panel’s request for justification on that point.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that in a time-toevent analysis, study power was a function of the number of events observed (disease progression in this case), rather than the number of patients recruited. To achieve 80% power in respect of the study’s primary endpoint (upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for the hazard ratio for progression-free survival by independent review committee (IRC) assessment using ITT analysis <1.25), it was calculated that 631 IRC-adjudicated progression events were required. To meet a tighter non-inferiority margin of 1.22, 794 events would be required to maintain 80% power.

In oncology studies which used an endpoint of PFS, there was frequently discordance between the number of patients deemed to have ‘progressed’ by the investigator vs those adjudicated to have progressed by the IRC. This typically resulted in a higher number of investigator-assessed PFS events compared with IRC-adjudicated events within any given data cut.

In line with the statistical analysis plan for COMPARZ, the dataset was analysed once 631 IRCadjudicated events had arisen. The analysis results were the first obligation of the conditional approval for pazopanib. The analysis included 659 IRCadjudicated events and 730 investigator-assessed events.

Although the EMA had asked GlaxoSmithKline to analyse the COMPARZ dataset once 794 investigatorassessed events had taken place, once the results based on the 659 IRC-assessed and 730 investigatorassessed events had been reviewed, the CHMP was satisfied that non-inferiority with respect to its criteria had been established, and it withdrew the requirement that GlaxoSmithKline undertake a further analysis once 794 investigator-assessed progression events had occurred.

GlaxoSmithKline emphasised that study power was related to the risk of failing to detect a true positive result (Type II error) and not to the risk of generating a false positive result (Type I error). Having fewer than 794 investigator-assessed progression events included in the analysis simply increased the risk of failing to demonstrate ‘true’ non-inferiority. The risk of detecting ‘false’ non-inferiority was unaffected. Despite having only 730 patients available for analysis, the CHMP was satisfied that the data was sufficiently strong to demonstrate non-inferiority.

In line with accepted practice, the study had been powered in respect of the primary endpoint not in respect of a sensitivity analysis such as that performed on the PP population.

Assuming ‘robustness’ referred to by the Panel meant the degree of certainty associated with a particular result, GlaxoSmithKline believed that it was best described by the 95% confidence interval associated with that result. As fewer patients were available for the PP analysis compared with the primary ITT-based analysis, the confidence intervals were consequently wider but were almost entirely overlapping as illustrated in the table above which summarized the relevant results from the COMPARZ study.

GlaxoSmithKline considered that it was inappropriate to compare the IRC-assessed PP population result to the 1.22 margin because firstly the EMA-defined 1.22 margin was always associated with investigator-assessed data, and secondly, the PP population result was a sensitivity analysis. GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the acceptance of the data by the CHMP attested to its robustness.

GlaxoSmithKline enclosed the agenda and training slides which related to the meeting in which the leavepiece had been briefed out to its sales representatives. It had been a face-to-face meeting during which the COMPARZ data had been presented by the medical team. GlaxoSmithKline included a further briefing document about the differences between the PP and ITT analysis.

GlaxoSmithKline could not submit a copy of the paper about the COMPARZ study which was due to be published because of the journal’s embargo policy. GlaxoSmithKline had been asked not to share the manuscript with anyone until publication but would provide the Authority with a copy once the embargo had been lifted.

GlaxoSmithKline reaffirmed that the leavepiece was an accurate, fair and balanced summary of the comprehensive data package submitted to, reviewed and accepted by the CHMP and therefore it did not consider that it had breached Clauses 7.2, 7.3, 7.4 or 7.8 or that a beach of Clause 2 was warranted for the reasons detailed above.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted Pfizer’s submission that the PP analysis was critical in allowing clinicians to judge the totality of the data and allow them to make informed treatment decisions regarding these two medicines. The Panel further noted that Pfizer considered that to present only the ITT analysis in the leavepiece but not label it as such was misleading and that both the ITT analysis and the PP analysis should be presented in all promotional materials.

Pfizer had further stated that it was critical that the data from COMPARZ were presented transparently and ethically to allow clinicians to make an informed treatment decision based on a good understanding of the relative efficacy of each medicine.

The Panel noted that the primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study was progression-free survival assessed by independent review, to be performed on the ITT population. In that regard the Panel noted the submissions from both parties about the relative merits of ITT vs PP analyses in noninferiority studies. The Panel noted that using either analysis was associated with differing strengths and weaknesses. Statistical guidance did not prohibit the use of an ITT analysis in non-inferiority studies. The EMA appeared to consider that the ITT analysis and the PP analysis were of equal importance and that their use should lead to similar conclusions for a robust interpretation of the result.

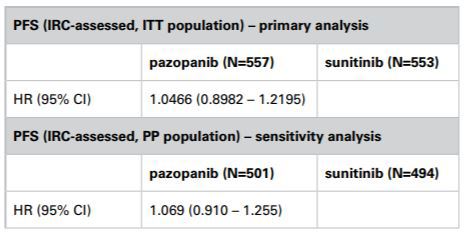

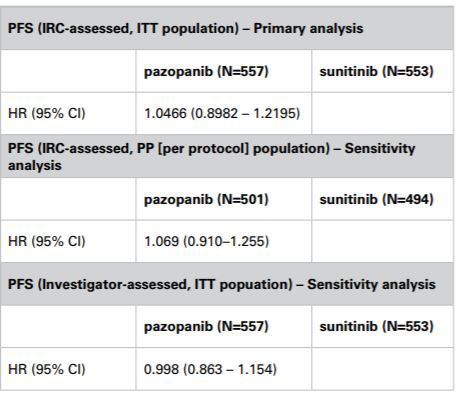

The Panel noted that the COMPARZ study had been designed such that the primary analysis would be conducted on the ITT population; progression-free survival would be assessed by independent reviewers. The CHMP, amongst others, had accepted that this design was appropriate. The Panel noted GlaxoSmithKline’s submission that the proposed study analysis plan had been reviewed by the CHMP and that although it had requested a tighter non-inferiority margin of 1.22 vs 1.25, it had not raised any concerns about the use of ITT as the primary analysis population. The Panel noted that a sensitivity analysis on the PP population had been included in the study and that the hazard ratios from that analysis were very similar to those from the ITT analysis with confidence intervals that overlapped (PP analysis 0.910 – 1.255 vs ITT analysis 0.8982 – 1.2195). In that regard the Panel considered that the results of the PP analysis and the ITT analysis appeared to be consistent. The primary ITT analysis met the CHMP defined primary endpoint of an upper bound of no more than 1.22 and thus demonstrated non-inferiority between Votrient and sunitinib. The Panel noted that when progression-free survival was assessed by investigators the confidence interval was 0.863 – 1.154 which also satisfied the limits set by the CHMP.

The Panel noted that the COMPARZ study objectives were set out on page 3 of the leavepiece and the primary endpoint was stated ie to evaluate noninferiority in progression-free survival between Votrient and sunitinib. It was not stated that that analysis would be in the ITT population. A diagram depicting the 1:1 randomisation of patients included the patient numbers in each treatment arm ie Votrient n=557 and sunitinib n=553. Patients randomized into a trial formed, by definition, the ITT population Although the graphs on page 4 of the detail aid headed ‘Primary Endpoint – PFS (independent review)’ and ‘Progression Free Survival (investigator review)’ respectively did not state that the analysis was performed on the ITT population, a table embedded into the two graphs noted the patients numbers in each treatment arm (ie Votrient n=557 and sunitinib n=553). In that regard the Panel considered that, although not specifically stated on page 4, readers could deduce, given the information on page 3, that the primary endpoint analysis was carried out on the ITT population. The Panel noted its comments above about the satisfaction of the CHMP primary endpoint. The Panel considered that although it would have been helpful to explicitly refer to the ITT population on page 4 of the detail aid, on balance the failure to do so was not misleading in that regard. No breach of Clauses 7.2 and 7.8 was ruled. This ruling was appealed by Pfizer.

The Panel noted Pfizer’s concern that to present the ITT analysis without the PP analysis was misleading. The Panel noted its comments above about the consistency of the primary ITT analysis and the PP analysis and considered that as the results were so similar, it was not, in the particular circumstances of this case, misleading to refer only to the ITT analysis. No breach of Clauses 7.2 and 7.3 was ruled. This ruling was appealed by Pfizer.

The Panel considered that the claims regarding the non-inferiority of Votrient vs sunitinib could be substantiated. No breach of Clause 7.4 was ruled. This ruling was appealed by Pfizer.

APPEAL BY PFIZER

Pfizer stated that the Panel appeared to have carefully considered the correctness or otherwise of the primary endpoint used in the COMPARZ study and therefore whether the COMPARZ study could be used to claim non-inferiority of Votrient vs sunitinib. Pfizer did not contend that this study had failed to meet the primary endpoint defined in the protocol. Rather, Pfizer argued that, because of the statistical principles related to non-inferiority studies, it was misleading to present only the ITT analysis (which was not conservative in the non-inferiority trial setting as it was in superiority studies) without specifying that this was the analysis used, and failing to show the equally important PP analysis. A full presentation of the results was critical in this context to maintain the highest standards of transparency.

Use of a single analysis of the endpoint in the setting of non-inferiority in the leavepiece

Pfizer noted that the Panel agreed that the EMA guidance stated that the ITT and PP analyses were of equal importance and that their use should lead to similar conclusions for a robust interpretation of the result. Pfizer submitted that from the results given below, it could be seen that the ITT and the PP analyses showed a magnitude of difference which might appear similar, (a hazard ratio of 1.046 and 1.069 respectively), in favour of sunitinib. The confidence intervals, though, did not lead to similar conclusions: the ITT suggested that the trial had met pre-defined criteria for non-inferiority, while this was not the case in the PP analysis.

Pfizer noted that the Panel had asked GlaxoSmithKline a number of supplementary questions about the power of the study. This suggested that the Panel considered that issues relating to the power of the study were crucial in explaining any potential differences between the hazard ratios of these two analyses. Pfizer alleged that GlaxoSmithKline’s answers were inaccurate, confusing and misleading.

In particular Pfizer questioned why, when asked why more patients were not recruited to meet the stricter endpoint requested by the EMA, GlaxoSmithKline described time to event analyses and study power being a function of the number of patients recruited. In fact, the EMA gave GlaxoSmithKline permission to analyse two separate protocols together in order to provide the power, and a protocol amendment was undertaken to achieve this (The CHMP assessment report (2010) for pazopanib). It was unclear why GlaxoSmithKline did not disclose this.

Pfizer further questioned why, when asked what power the study had to detect non-inferiority given the stricter EMA requirements, GlaxoSmithKline stated that ‘study power was related to the risk of failing to detect a true positive result (Type II error) and was not related to the risk of generating a false positive result (Type I error)’. While this was true for superiority trials, it was much more complicated in the non-inferiority setting where a lack of power could bias towards conclusions of non-inferiority (ie a false positive result). As a result, GlaxoSmithKline appeared to dismiss incorrectly the risk of underpowering a non-inferiority study. This answer from GlaxoSmithKline, which failed to demonstrate a clear and transparent understanding of the principles underlying non-inferiority design, again highlighted the serious risk that failure to present these data in their totality could give rise to similar misunderstandings amongst treating clinicians.

The Panel went on to ask GlaxoSmithKline about the robustness of the PP analysis given the smaller patient numbers. GlaxoSmithKline responded that the confidence intervals were wider for the PP analysis and that they overlapped entirely the ITT. In fact, the confidence interval was not much wider in the PP analysis relative to the ITT analysis, but the whole estimate (point estimate for the hazard ratio as well as the upper and lower limits of the confidence interval) was shifted right, further in favour of sunitinib, and they did not overlap at the lower end.

GlaxoSmithKline suggested that reducing the number of events would make it less likely for noninferiority to be shown, while in fact the opposite might be true. Even with smaller numbers in the PP analysis, which could bias the study towards a finding of non-inferiority, the study did not meet the non-inferiority criteria in the PP analysis. In an open-label study, that was of concern and a further reason why the PP analysis was so critical to an interpretation of this study.

Pfizer did not agree that the CONSORT statement did not apply to presenting the results of trials in marketing materials, and that the basic principles of the CONSORT statement were not the basic principles underpinning the Code. Given the very difficult nature of the statistical principles underpinning non-inferiority studies, the poor understanding of these studies amongst clinicians and the fact that COMPARZ was the first non inferiority study conducted in kidney cancer the CONSORT statement required that the PP analysis be reported. For the same reasons, Pfizer expected the PP analysis be used in marketing materials.

The regulatory framework and why the COMPARZ study was acceptable to the CHMP and EMA

Pfizer noted that GlaxoSmithKline relied heavily in its response on the opinion of a journal peer review panel and the CHMP and the granting of a full marketing authorization subsequent to the COMPARZ study being submitted to the CHMP to justify the presentation of only one analysis in its marketing materials. Notwithstanding that the study had satisfied the CHMP, this must be taken in the context of why the COMPARZ study was requested and the role of the regulator in this regard.

First-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma was a crowded market. The first medicine of the modern era approved in this setting, sorafenib (Nexavar), was granted a marketing authorization in a pivotal study with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 5.5 months (167 days) in a head-to-head study vs placebo (Nexavar summary of product characteristics (SPC)). Sunitinib demonstrated a PFS of 11 months vs an active comparator very soon after (Sutent SPC). Several years later, GlaxoSmithKline submitted the pivotal phase III trial of pazopanib vs placebo (study VEG105192) to the CHMP, which demonstrated a PFS of 11 months in patients treated with pazopanib (Votrient SPC). Although both sunitinib and pazopanib gave PFS of 11 months in their pivotal trials, these numbers could not be directly compared because there might have been differences in the baseline characteristics of the patients in the trials. Since the comparator arms were also different (placebo in the pazopanib trial and an active comparator, Interferon, in the sunitinib trial), cross trial comparisons of efficacy were not possible.

Pfizer alleged that GlaxoSmithKline proceeded with the placebo-controlled study despite advice, in December 2006, that such a study would not be recommended for seeking a marketing authorization (CHMP assessment report (2010) for pazopanib). This advice was repeated in February 2007, before GlaxoSmithKline sought further advice in October 2007 as to what active comparator study the authority would recommend. The CHMP recommended a blinded, head-to-head study vs sunitinib (VEG 108844, later to be called the COMPARZ study). GlaxoSmithKline undertook the study in an open-label fashion (thereby increasing risk of bias, which was particularly problematic in the setting of non-inferiority).

Pfizer alleged that in granting the initial conditional licence for pazopanib, the CHMP assessed the pivotal phase III head-to-head study, along with the rest of the data package, and concluded that the risk-benefit assessment was favourable, and that pazopanib was an effective medicine. Despite this, and given the new therapies available by the time of the CHMP assessment of pazopanib, the CHMP stated ‘Therefore, the CHMP was of the opinion that even though in the specific case of pazopanib it had been shown that the product was effective, an active comparator with other [tyrosine-kinase] inhibitors was necessary in order to rule out that the use of pazopanib would mean a loss of opportunity for the patients’ (CHMP assessment report (2010) for pazopanib).

Pfizer alleged that by this stage the COMPARZ study was ongoing. While the CHMP then discussed the COMPARZ study in detail with GlaxoSmithKline and suggested some changes to the study (eg reducing the non-inferiority margin) it might be inferred from the EPAR and other publically available regulatory documents that the CHMP did not hold the COMPARZ study to the same regulatory requirements as for a pivotal noninferiority study. This would explain why the CHMP assessment of COMPARZ would be at odds with the guidance published from the EMA which was unequivocal when it stated ‘in a non-inferiority trial, the full analysis set and the PP analysis have equal importance and their use should lead to similar conclusions’ (EMA guideline 2000, Schumi and Wittes, 2011). This had not been demonstrated in COMPARZ where one analysis led to a conclusion of non-inferiority, the other did not.

Pfizer alleged that the regulator required the head-to-head COMPARZ study to answer the question of relative efficacy and then made its decision to grant a full licence on the basis of the totality of the data presented. This was in the context of already having assessed significant additional data from GlaxoSmithKline on the benefits and risks of pazopanib. But it was crucial to note that clinicians did not have access to the same quality of data when making actual treatment decisions. Indeed clinicians had rightly demanded for some time that the same amount of data be given to them to help their decision making as was given to the regulators. Clause 7.2 stated that ‘… claims … must be based on an up-to-date evaluation of all the evidence and reflect that evidence clearly. They must not mislead either directly or by implication, by distortion, exaggeration or undue emphasis. Material must be sufficiently complete to enable the recipient to form their own opinion of the therapeutic value of the medicine’ (emphasis added by Pfizer).

Pfizer alleged that GlaxoSmithKline emphasised acceptance of the trial for publication by a peer reviewed journal as vindication of the trial being positive and the analysis presented in the leavepiece being fair and balanced. However, a study of the size and importance of COMPARZ should always be accepted for publication regardless of the result of the study, and so publication in a peer reviewed journal alone did not imply acceptance of noninferiority. Crucially, as stated by GlaxoSmithKline, the peer review panel did require both the ITT and the PP analyses be submitted to the journal.

Pfizer finally noted that pazopanib was granted full approval in the US on the basis of the pivotal phase III trial vs placebo. The US regulator had not required COMPARZ to be submitted and had not judged the study against its own guidance.

The approach of other prescription medicines advertising authorities around the world in this setting

Pfizer alleged that non-inferiority in oncology was a relatively new approach, but was likely to increase, along with resultant advertising to clinicians, of a number of ‘me too’ small molecules such as pazopanib came to market. Although there was no specific guidance in the UK or European Code, the Canadian Pharmaceutical Advertising Advisory Board (PAAB) had issued a comprehensive document in this setting, which reiterated a number of the key points highlighted above and made a number of key recommendations:

Sample size: Under section 2 of the PAAB guidance, ‘Key Pitfalls’, it stated that ‘unlike superiority trials, an underpowered non-inferiority trial may be more likely to produce an untrue positive result’ and that type II error had heightened importance in noninferiority trials and must be managed. If sample size was inadequate, a non-inferiority trial could lead to false claims of non-inferiority when a medicine was, in fact, worse than a comparator. The PAAB suggested that description of interim analyses, power calculations etc should be provided in all advertising materials. Although the management of power in this trial did not form part of Pfizer’s original complaint, it was clear that the Panel considered it was a key concern, and Pfizer therefore believed that further clarity from GlaxoSmithKline was required on this point.

Analysis sets: The PAAB stated:

‘For each analysis, provide the number of participants contributing to estimates of effectiveness. If the number is smaller than the intent-to-treat number, specify how the denominator was derived. (ie state from a per protocol analysis and associated criteria).

Both ITT and per protocol results should be assessed (and both should support the conclusion of non-inferiority).’

The PAAB stated that these analyses above should be included in all advertising materials.

For the reasons outlined above, Pfizer alleged that the presentation of the COMPARZ study in the leavepiece was in breach of Clauses 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, and 7.8.

RESPONSE FROM GLAXOSMITHKLINE

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer had made a number of serious allegations, incorrect paraphrases and disparaging remarks and it addressed these first.

Pfizer alleged that GlaxoSmithKline had misled the Panel by not disclosing the details of a protocol amendment undertaken to adequately power the COMPARZ study. This issue was raised by Pfizer during previous inter-company dialogue and addressed by GlaxoSmithKline:

‘The clinical trial protocol for VEG108844 describes the inclusion of subjects enrolled in both VEG108844 and VEG113078 for evaluation in the pre-specified analyses of primary and secondary endpoints. As both VEG108844 and VEG113078 were of virtually identical design, pooling results of the two studies could be undertaken without statistical difficulties arising. The trial protocol, including the proposal to perform a pooled analysis has, in line with standard practice, been reviewed and accepted by the independent data safety monitoring board, regulatory authorities and various ethics committees.’ (GlaxoSmithKline’s letter to Pfizer dated 9 January 2013).

GlaxoSmithKline considered that as Pfizer had not pursued this dialogue further it had accepted the validity of pooling data obtained from both these protocols as constituting the pre-specified analysis of the COMPARZ study.

‘We are prepared not to pursue this section of our complaint further at this time. We understand that further data from trials VEG108844 and VEG113078 may be presented at ASCO GU. We hope that these further data go some way to answering our questions in this area. That said, we reserve the right to raise this issue again if, for example, the separate analyses are not presented or do not individually support the overall conclusions of the pooled analysis.’ (Pfizer letter to GlaxoSmithKline dated 15 January 2013).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer had not raised this issue during the course of this current complaint, either during inter-company dialogue or when it referred the complaint to the PMCPA. Since this matter did not appear relevant to any of the specific complaints which Pfizer referred to the PMCPA, GlaxoSmithKline did not believe that this issue needed to be addressed in its response to Pfizer’s complaint. GlaxoSmithKline therefore strongly refuted any suggestion that it had misled the PMCPA in its response to this complaint.

Pfizer stated that GlaxoSmithKline’s response to the PMCPA of 2 July was inaccurate and confusing. GlaxoSmithKline noted that Pfizer incorrectly paraphrased GlaxoSmithKline’s letter as follows:

- GlaxoSmithKline stated in its letter to the PMCPA (2 July 2013):

‘... study power is a function of the number of events observed (in this case disease progression), rather than the number of patients recruited.’

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer incorrectly paraphrased this in its appeal as:

‘GlaxoSmithKline described time to event analyses and study power being a function of the number of patients recruited.’

- GlaxoSmithKline stated in its letter to the PMCPA (2 July 2013,):

‘... the confidence intervals are consequently somewhat wider, but were almost entirely overlapping’ [table 1 contained exact confidence interval values].’

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer had incorrectly paraphrased this in its appeal as:

‘GlaxoSmithKline responded that the confidence intervals were wider for the PP analysis and that they overlapped entirely the ITT.’

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the relevant confidence intervals from the COMPARZ study were as follows (COMPARZ results – www.GSKclinicalstudyregister.com):

GlaxoSmithKline stated in its letter to the PMCPA (2 July 2013, page 2):

‘... having fewer than 794 investigator-assessed progression events included within the analysis simply increased the risk of failing to demonstrate “true” non-inferiority. The risk of detecting “false” non-inferiority is unaffected’.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer had incorrectly paraphrased this in its appeal as:

‘GlaxoSmithKline suggests that reducing the number of events would make it less likely for non-inferiority to be shown, while in fact the opposite may be true.’ GlaxoSmithKline was surprised that Pfizer had chosen to disparage both its and the CHMP’s scientific work as follows:

- Pfizer commented in its appeal:

‘... it might be inferred from the EPAR and other publically available regulatory documents that the CHMP did not hold the COMPARZ study to the same regulatory requirements as for a pivotal non-inferiority study. This would explain why the CHMP assessment of COMPARZ would be at odds with the guidance published from the EMA....’

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer was perfectly entitled to discuss its inferred conclusion of lower standards regarding the approach taken by the CHMP to the licensing of pazopanib with the regulatory authorities. However, GlaxoSmithKline was of the opinion that such concerns were not relevant to the complaint.

- Pfizer commented in its appeal in Point 2 below:

‘GlaxoSmithKline go on to state that they had not tried to infer equivalence between the two medicines at all, as the non-inferiority design of the trial was clear throughout the detail aid. This is disingenuous.’

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer’s assertion of being disingenuous was disparaging and entirely unjustified. The non-inferiority design and result of the COMPARZ study was made abundantly clear throughout the leavepiece.

GlaxoSmithKline concurred with the Panel’s conclusion with respect to this particular matter: ‘The Panel did not consider that readers would view this explanation [of the question posed to patients in the PISCES study] as a claim that Votrient and sunitinib had equivalent efficacy.’

GlaxoSmithKline now addressed the points made by Pfizer in its appeal.

COMPARZ endpoint data

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the COMPARZ study design, including choice of primary endpoint, primary analysis population and statistical power, was reviewed and accepted by the EMA as being adequate to meet GlaxoSmithKline’s post-licence requirement to demonstrate non-inferiority for pazopanib vs sunitinib. Furthermore, the results of COMPARZ had been reviewed and accepted by the CHMP leading to its conclusion that the data demonstrated non-inferiority of pazopanib to sunitinib for progression-free survival. The same conclusion was reached by the peer review panel of a leading medical journal which demonstrated its acceptance of the trial methodology, result and importantly the conclusion of non-inferiority.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that Pfizer’s continued assertion that ITT analysis was ‘not conservative in the non-inferiority trial setting as it was in superiority studies’ in itself failed to demonstrate an up-to-date evaluation of current statistical thinking. GlaxoSmithKline referred to its response above where the academic debate on the relative merits of ITT vs PP analysis in non-inferiority trials was discussed.

GlaxoSmithKline noted that the current Votrient SPC did not include the PP sensitivity analysis, nor did it state that the primary analysis of PFS was performed on the ITT population. Other examples of regulatory-approved documents presenting noninferiority data in a similar fashion was provided in earlier correspondence.

GlaxoSmithKline also highlighted that the CHMP, journal peer review panel and Panel all concluded that the results of the PP analysis (a pre-specified sensitivity analysis) were consistent with the ITT analysis (primary analysis). This further supported GlaxoSmithKline’s position that due to the consistency between the two results it was not, in this case, misleading to only refer to the ITT analysis in promotional materials, a conclusion also reached by the Panel.

GlaxoSmithKline considered that the leavepiece was not misleading and not in breach of Clauses 7.2, 7.3, 7.4 or 7.8.

GlaxoSmithKline subsequently provided the published version of the COMPARZ study (Motzer et al 2013). A copy was provided to Pfizer for comment.

FINAL COMMENTS FROM PFIZER

Pfizer was concerned that its intentions in its appeal had been misinterpreted. GlaxoSmithKline claimed that Pfizer had made some serious allegations, and used some incorrect paraphrasing and disparaging remarks. Pfizer responded to these in turn:

Serious allegations

Pfizer stated that it had discussed the pooling of protocols as part of inter-company dialogue between December 2012 and March 2013 and it accepted the explanation given by GlaxoSmithKline in relation to the protocol amendment. Pfizer questioned why GlaxoSmithKline failed to highlight key information in response to an inquiry from the Panel about the power of the COMPARZ study given the stricter EMA requirements. Pfizer simply noted that GlaxoSmithKline’s response was factually inaccurate (by omission) and therefore confusing and misleading.

Incorrect paraphrases

Pfizer acknowledged that its appeal did not directly quote GlaxoSmithKline in some places. However, this did not materially impact the information it had conveyed, particularly as the Panel had the original letter from GlaxoSmithKline.

Disparaging remarks

Pfizer was surprised that GlaxoSmithKline considered that its appeal was disparaging, either to the CHMP or to GlaxoSmithKline. Pfizer clarified what it had stated:

- Pfizer did not disparage the work of the CHMP.

Pfizer’s appeal sought to explain why it might be possible that the CHMP would take the results of the COMPARZ study and grant a full licence to pazopanib, despite the two analysis sets (PP and ITT) clearly leading to differing conclusions (in ITT, non-inferiority was demonstrated, but in PP it was not). Pfizer did not reiterate its conclusions here.

- Pfizer did not intend to disparage GlaxoSmithKline in its appeal in Point 2 below when it stated that the company was being disingenuous when it claimed it was not trying to infer equivalence. However, given GlaxoSmithKline’s response to this section indicating the misinterpretation of Pfizer’s initial comments, it did concede that the word ‘disingenuous’ in that context was too strong.

APPEAL BOARD RULING

The Appeal Board noted that the primary endpoint of the COMPARZ study was met in that Votrient was shown to be non inferior to sunitinib with respect to progression-free survival assessed by independent reviews performed on the ITT population.

The Appeal Board noted that page 3 of the leavepiece included the COMPARZ study objectives and listed the primary and secondary endpoints. A figure depicted the study design showing a 1:1 randomisation of patients including the number of patients in each treatment arm (Votrient n=557 and sunitinib n=553) and although it was not stated patients randomised into a trial by definition formed the ITT population. The graphs on page 4 included the same patient numbers and although again it was not stated, it could be concluded from the previous page that this was also the ITT population and analysis. The Appeal Board noted that an ITT analysis more closely reflected clinical practice.

The Appeal Board noted that there was conflicting academic debate on the merits of ITT vs PP analysis. In relation to this particular case the Appeal Board noted that a sensitivity analysis of the PP population had been included in the COMPARZ study and that hazard ratios from that analysis were very similar to those from the ITT analysis with confidence intervals that overlapped (PP analysis 0.910 – 1.255 vs ITT analysis 0.8982 – 1.2195). The Appeal Board considered that the differences between the ITT and PP results were unlikely to translate as a meaningful difference to an individual patient. It appeared that the ITT and PP results were not inconsistent.

The Appeal Board noted that the CHMP had accepted that the design of the COMPARZ study was appropriate (subject to a tighter non-inferiority margin of 1.22) in that the primary endpoint was based upon the ITT analysis. The Appeal Board also noted that the COMPARZ study had now been accepted and published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The Appeal Board accepted that it might have been helpful to label the ITT analysis. However the Appeal Board noted its comments above and considered that Pfizer had not established that the failure to explicitly state that the analysis was on the ITT population, on Page 4 of the leavepiece, was misleading. The Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of no breach of Clauses 7.2 and 7.8 of the Code. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

The Appeal Board noted its comments above about the CHMP, publication in a peer reviewed journal and that the ITT and PP analysis results were not inconsistent. The Appeal Board therefore considered that it was not misleading to refer only to the ITT analysis. The Appeal Board upheld the Panel’s ruling of no breach of Clauses 7.2 and 7.3. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

The Appeal Board considered that given its comments above the claims regarding the non-inferiority of Votrient vs sunitinib could be substantiated and it upheld the Panel’s ruling of no breach of Clause 7.4. The appeal on this point was unsuccessful.

2 Claim ‘COMPARZ complements the PISCES study which demonstrated patient preference for Votrient.’

This claim appeared on page 10 of the leavepiece.

COMPLAINT

Pfizer stated that the PISCES study was a two stage, randomized, cross-over study where patients received one cycle of each medicine (sunitinib and pazopanib) in turn, separated by a washout period. At the end of the study period, patients were asked which they would prefer to take assuming that both medicines were equally efficacious.

Pfizer stated that a non-inferiority trial could not prove equal efficacy. As such, no claims about patient preference could be made for pazopanib as such claims would be based on a false assumption and so also be misleading.

Pfizer alleged breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4.

RESPONSE

GlaxoSmithKline noted that PISCES was a randomised, double-blind, cross-over, patient preference study of pazopanib vs sunitinib in treatment-naive locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. The objective was to evaluate any difference in patient preference between the two medicines with all patients having taken both. Patient preference was an emerging, challenging area of research which was being undertaken increasingly across a range of therapeutic areas to help inform treatment decisions.

GlaxoSmithKline considered that patient preference in the setting of advanced renal cancer was a particularly important consideration for physicians and patients because:

- neither pazopanib nor sunitinib were generally considered to be curative, therefore the quality of the patient’s remaining life was particularly important

- treatment with medicines such as pazopanib and sunitinib would often continue for a substantial proportion of the remaining, limited, lifespan of patients

- these medicines were associated with significant side effects which could substantially impact the quality of life of patients.

GlaxoSmithKline stated that in order to assess patient preference in isolation, it was necessary to ask patients to assume, for the purposes of the study, that both medicines worked equally well, particularly in the field of oncology where disease status did not always directly correlate with symptoms.

GlaxoSmithKline noted that in inter-company dialogue, Pfizer accepted that a patient preference study might have to assume equal efficacy between the medicines being compared, in order to elucidate patient preference in isolation. As stated in the leavepiece, patients were asked: ‘Now that you have completed both treatments, which of the two drugs would you prefer to continue to take as the treatment for your cancer, assuming that both drugs will work equally well in treating your cancer?’ (patients selected either first treatment, second treatment or no preference). Therefore the study was not based on a false assumption but instead, a necessary assumption for this type of research. The assumption of equal efficacy was considered to be reasonable when PISCES was designed since indirect comparative data suggested that pazopanib was similar to sunitinib in terms of efficacy in treatment naive patients (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.55, 1.56) (McCann et al 2010).

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that PISCES was initiated, conducted, analysed and presented before the outcome of the only head-to-head efficacy study (COMPARZ) was known. Therefore clinical equipoise existed around the relative efficacies of pazopanib and sunitinib when PISCES was undertaken. The design of PISCES, including the assumption used, was discussed with clinical experts, subjected to external scrutiny, and accepted by regulatory authorities and ethics committees. Moreover, it was unlikely that patients to whom the question was addressed would have understood the difference between one treatment being non-inferior to another or working equally well.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that the non-inferiority design of the COMPARZ study was abundantly clear throughout the leavepiece, including the summary given on page 10. The final bullet point on page 10 which Pfizer was concerned about stated that ‘COMPARZ complements the PISCES study which demonstrated patient preference for VOTRIENT (70% preferred VOTRIENT vs. 22% who preferred sunitinib (8% no preference; 90% CI (for difference); 37.0%-61.5%; p<0.001).’ which was a straightforward summary of the results from the PISCES study. The footnote at the bottom of page 10 clarified the study design.

GlaxoSmithKline stated that it had not tried to infer equivalence of pazopanib and sunitinib in terms of efficacy and did not believe that readers would be left with that impression. The non-inferiority design and result from the COMPARZ study were prominently described throughout the leavepiece.

GlaxoSmithKline submitted that it had included the final bullet point on page 10 because it considered that clinicians treating patients with renal cell cancer would want to consider a range of factors when deciding which treatment to prescribe. These factors included efficacy, adverse event profile and patient preference, alongside various patient-specific factors. Therefore GlaxoSmithKline considered that presenting data which focussed on patient preference alongside efficacy data was useful to clinicians. The PISCES trial design and assumption were transparent in the leavepiece. In particular, by presenting both PISCES and COMPARZ data together, clinicians could interpret the PISCES data, knowing that for the purposes of the study patients were asked to assume that both treatments work equally well, in light of the non-inferiority demonstrated by the head-to-head efficacy results from COMPARZ. Clinicians would be in the best position to make appropriate prescribing decisions by having a clear appreciation of the objectives, design, results and limitations of both studies. GlaxoSmithKline stated that it did not consider that because patients had been asked to make a necessary assumption, the results of such a study could never be used in a promotional context. As previously acknowledged by Pfizer, that patients were asked to assume that both medicines under investigation worked equally well was a necessary feature of the design of this kind of study. The design of PISCES, alongside the key study result, was transparently presented in leavepiece. GlaxoSmithKline reiterated that the PISCES study did not and was never intended to support a claim of equivalence. GlaxoSmithKline thus did not consider that page 10 of the leavepiece was misleading and it denied breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted that the PISCES study was established to determine whether patients preferred Votrient, sunitinib or had no preference for either. In the Panel’s view patients had to enter such a study on the premise that the two medicines in question had equal efficacy. The Panel noted that, in small print, at the bottom of page 10 of the leavepiece it was stated that patients were asked ‘Now that you have completed both treatments, which of the two drugs would you prefer to continue to take as the treatment for your cancer, assuming that both will work equally well in treating your cancer?’ The Panel did not consider that readers would view this explanation as a claim that Votrient and sunitinib had equivalent efficacy. The Panel considered that given the outcome of COMPARZ, a patient preference study based on the question above was not unreasonable; patients would not understand the question if they were asked to assume that the two medicines were non-inferior. In the Panel’s view the claim at issue was not misleading as alleged and could be substantiated. No breach of Clauses 7.2, 7.3 and 7.4 were ruled.

APPEAL BY PFIZER