Case Summary

Novartis complained about a CellCept (mycophenolate mofetil) booklet entitled ‘Are you concerned about GI [gastrointestinal] complications after transplantation?’ issued by Roche. CellCept was indicated in combination with ciclosporin and corticosteroids for the prophylaxis of acute transplant rejection in patients receiving allogenic, renal, cardiac or hepatic transplants. Novartis supplied Myfortic (enteric coated mycophenolate sodium) which was also used in combination with ciclosporin and corticosteroids but only for the prophylaxis of acute transplant rejection in adults receiving allogenic renal transplants. Novartis alleged the booklet misrepresented the role of immunosuppression, specifically CellCept, in the aetiology of GI complications following transplantation and was inconsistent with the CellCept summary of product characteristics (SPC).

Page 1 was headed ‘GI complications in transplantation’. In a list of causes of GI adverse events infections was at the top and drug-induced effects, for example antibiotics and immunosuppressants, was at the bottom. Novartis believed this oversimplified the aetiology of GI adverse events to minimise the association with CellCept. In the context of a CellCept promotional piece, and in view of the prominence of GI side effects in the CellCept SPC, immunosuppression (if not specifically CellCept) should be listed first in any ranking of causes for GI side effects after transplantation; both because it was directly toxic to the GI tract and because it was a potent immunosuppressant that increased the risk of infections which might be associated with GI symptoms.

The Panel noted from the CellCept SPC that treatment should be initiated and maintained by appropriately qualified transplant specialists and that the principal adverse reactions associated with therapy included diarrhoea, leucopenia, sepsis and vomiting. The SPC also stated that all transplant patients were at increased risk of opportunistic infections; the risk increased with total immunosuppressive load. The most common infections in patients followed for at least one year were candida mucocutaneous, CMV viraemia/syndrome and Herpes simplex. With regard to GI adverse reactions, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and nausea were listed as very common (≥1/10) and GI haemorrhage, peritonitis, ileus, colitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastritis, oesophagitis, stomatitis, constipation, dyspepsia, flatulence and eructation were listed as common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10).

The Panel noted that on the page headed ‘GI complications in transplantation’, specific mention was made regarding GI adverse events with CellCept. The page stated that ‘The use of CellCept has led to significant reductions in graft rejection and improved long-term graft survival and function, but GI effects are still a concern with immunosupression’. Druginduced effects were included on the list of causes of GI adverse events. The list did not give any indication of the incidence or ranking of the importance of infection, surgery, concomitant diseases or drugs in causing GI complications.

The Panel noted that Rubin (2001) stated that it was often very difficult to distinguish between infection-related and immunosuppression-related GI complications after transplantation. The causes might differ depending upon the time post-transplant and this time line was helpful in determining whether a GI complication was likely to be related to infection rather than a specific effect of an immunosuppressant medicine.

The Panel did not accept that the list oversimplified the aetiology of GI adverse events. The booklet was aimed at a specialised audience. No breach of the Code was ruled.

Page 2 was sub headed ‘Determining the probable cause can prove a prudent course of action’ and included two quotations: ‘Inappropriate dose reduction of an immunosuppressive agent that may not be the cause of the diarrhoea may result in an unnecessarily increased risk of acute rejection, the long-term impact of which is far more detrimental to patient or graft survival.’ (Pescovitz et al 2001) and ‘As infections very often have GI symptoms, it is important to rule out infection before looking to the immunosuppressive drug regimen as the cause of a patient’s GI problem.’ (Rubin 2001).

Novartis alleged that these quotations suggested that intervention to reduce GI side effects during Cellcept therapy should be delayed until GI symptoms had been investigated and implied that the true cause was frequently independent of the dose of immunosuppression given. These views were not consistent with the CellCept SPC. In addition, it was not made clear that the quotations represented opinions expressed in a journal supplement which had not been peer-reviewed rather than the evidence based conclusion of a study.

The Panel did not consider that the page was inconsistent with the CellCept SPC as alleged. The CellCept SPC listed GI adverse events as well as generally linking immunosuppression to infections.

The specialist audience would be well aware of the difficulties with immunosuppression treatment. It was a matter for the specialists to decide whether to lower the dose of CellCept and when this should happen. The Panel did not accept that the page implied that the true cause of GI complications was frequently independent of the dose of immunosupressant used. In the Panel’s view the main message of the page was summed up in the sub-heading ‘Determining the probable cause can prove to be a prudent course of action’.

The Panel did not consider that the Code required promotional material to indicate that a quotation had been taken from a source that had not been peer-reviewed as alleged. The Code required quotations to be factual and accurate and not misleading. The source needed to be cited. The Panel ruled that on the evidence before it there was no breach of the Code.

Page 3 was sub headed ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’ and presented data from Maes et al (2003) on 26 renal transplant patients on an immunosuppressive regime which included CellCept. An infectious cause of diarrhoea was demonstrated in approximately 60% (n=13). A graph showed that of those thirteen patients 92% (n=12) had diarrhoea primarily treated with antimicrobial agents; in the remaining patient, with a concomitant malignant disorder, immunosuppressant therapy was stopped. The page concluded that ‘Diarrhoea was successfully treated with antimicrobial agents without the need for permanent reduction or cessation of immunosuppressant’.

Novartis alleged that the strong claim of the ‘proven’ benefit of excluding infection was not supported by the data presented. Half of the 26 patients with diarrhoea, selected as a subset of 765 patients, had an infectious cause of their diarrhoea. This was clearly not a ‘proven benefit’, particularly when one considered that CellCept itself predisposed to infection through immunosuppression.

Furthermore, the use of a graph with an impressive 92% graphic created a misleading impression of robust support for the claim.

The data presented related specifically to persistent afebrile diarrhoea but the headings were ‘Managing GI adverse events’ and ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’. Diarrhoea was only one of the GI adverse events listed in the CellCept SPC and no evidence was supplied for the benefit of excluding infection in the remainder.

The Panel noted that the graph on the page headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ showed that 92% of patients had diarrhoea treated primarily with antimicrobial agents. A sub-heading read ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’. The Panel considered that at first glance the page seemed to suggest that in 92% of patients with GI adverse events, diarrhoea could be controlled with

antimicrobials without the need to reduce the dose of immunosuppressant. This was not the case. The 92% related to the subset of patients with persistent afebrile diarrhoea in whom an infectious cause was found ie 13 patients. In the other patients in whom no infection was determined, immunosuppressive therapy was either reduced or stopped. Thus in an original group of 26 patients with afebrile diarrhoea, an infectious cause was demonstrated in 13, only 12 of whom were successfully treated with antibiotics ie <50% (12/26) as opposed to the 92% (12/13) depicted in the graph. The Panel considered that the page was misleading in this regard. The Panel also considered that it was misleading for a page headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ to focus only on data in patients with persistent afebrile diarrhoea.

The graph presented the data accurately but in the Panel’s view was not presented in such a way as to give a clear, fair, balanced view of the data. It was visually misleading. A breach of the Code was ruled. The Panel did not consider that the page failed to maintain a high standard.

Novartis alleged that pages 4 and 5, headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ and ‘Managing infectious diarrhoea’ contributed to the impression that infection was the most important cause of GI upset and that it was independent of immunosuppression (Cellcept). The treatment algorithm suggested that immunosuppression should only be considered a cause for GI upset once infection had been excluded.

The Panel did not agree with Novartis’ submission.

The subheading implied that it was important to distinguish between infection-related and immunosuppression-related GI complications. In the Panel’s view the pages encouraged a pragmatic approach ie that the cause of diarrhoea should be established before any treatment changes were introduced. The Panel did not consider that the pages were misleading and thus ruled no breach of the Code.

Page 7 ‘Managing non-infectious diarrhoea’, referred to 10 patients of the 23 patients with afebrile diarrhoea that did not have an infectious cause and were presumed to have drug-induced diarrhoea (Maes et al). This was followed by ‘All immunosuppressant regimens are associated with diarrhoea to a greater or lesser extent’. The frequency of study-reported diarrhoea post transplantation was given in a table.

Novartis stated that in an attempt to create a perception that the licensed use of CellCept was no more associated with GI adverse events than other immunosuppressants, GI adverse event rates seen with a number of alternative regimens were presented under the heading ‘Frequency of studyreported diarrhoea post transplantation’. However, the combination of tacrolimus and CellCept was not licensed and the use of ciclosporin and sirolimus in combination beyond three months (as per the reference cited) was specifically contraindicated in the sirolimus SPC, making this another unlicensed safety claim.

The Panel noted that the combination of CellCept and tacrolimus was not mentioned in the therapeutic indications, Section 4.1, of the CellCept SPC.

Mention was made in Section 4.5 interactions. The Panel did not consider that in the context of the table it was unreasonable to include details of the frequency of diarrhoea with this combination.

Ciclosporin and sirolimus were licensed for use for 3 months. The Panel did not consider in the context of the page at issue that the information about the frequency of diarrhoea with regard to CellCept and tacrolimus and ciclosporin and sirolimus were unlicensed safely claims as alleged. No breach of the Code was ruled although the Panel considered that the information could have been better presented to make the limitations clear.

Novartis alleged that page 8 of the booklet headed ‘Managing non-infectious diarrhoea’ and sub headed ‘Is there a role for enteric-coated mycopenolate sodium (EC-MPS) [Myfortic] in

reducing GI complications?’, disparaged its product, Myfortic. It presented a hypothesis based on a single bioavailability study that compared oral and IV administration of CellCept (ie a study that did not contain Myfortic. The hypothesis, which relied on the faulty premise of a single potential mechanism (topical effect), was used to support the statement ‘As such, it is not surprising that the 4 Code of Practice Review February 2007 enteric coat of MPS has no impact on GI complications’. It ignored alternative potential mechanisms, such as pharmacokinetic differences between the products.

The statement ‘EC-MPS has no advantage on tolerability over CellCept and no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept’, was referenced to a letter of opinion, written by a single clinician and in French, and was not an evidence based conclusion. Data comparing the rate of diarrhoea with CellCept and Myfortic was taken from a study which excluded patients unable to tolerate CellCept and as such provided little insight into the relative tolerability of the two agents. The statement also ignored the fact that the exploration of potential GI differences between the products remained the subject of a study.

The Panel noted that Salvadori et al (2003) compared CellCept with Myfortic and concluded that the products were therapeutically equivalent with a comparable safety profile. Within 12 months 15% of Myfortic and 19.5% of CellCept patients required dose changes for GI adverse events (p=ns). The study was not designed to statistically detect differences between treatment groups in terms of GI tolerability. The claim that [Myfortic] had no impact on GI complications was a strong one. The Panel noted that although the claim ‘[Myfortic] has no advantage on tolerability over CellCept and no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept’ was referenced to a single author, it appeared to be a quotation in that paper from a larger body, it was thus not just the opinion of a single clinician.

Novartis had not submitted data to support its complaint although a study was ongoing.

The comparison of rates of diarrhoea were from Budde et al (2003). The discussion noted that patients entered into the study were receiving and therefore tolerating [CellCept] at a dose of 2000mg which might introduce a bias. The Panel considered that the page had not put this data in context. It was inappropriate to follow the subheading ‘Is there a role for enteric coated mycophenolate sodium (ECMPS) in reducing GI complications’ with data referring only to CellCept.

The Panel noted that according to the SPCs for CellCept and Myfortic, diarrhoea was a very common side effect with both (≥ 10%). However the other very common GI side effects of CellCept (vomiting, abdominal pain and nausea) only occurred commonly (≥ 1% and <10%) with Myfortic.

Similarly some of the commonly occurring GI disorders with CellCept (eructation, ileus, oesophagitis, gastrointestinal haemorrhage) were uncommon (≥ 0.1% and <1%) with Myfortic. Thus, although both products were associated with a number of similar GI disorders there seemed to be a lessening of effect with Myfortic.

The Panel again noted that subheadings referred to GI complications as a whole whereas some of the data presented referred specifically to diarrhoea. On balance the Panel considered that the page

disparaged Myfortic and a breach of the Code was ruled. This ruling was appealed by Roche.

The Appeal Board was concerned about the content and layout of the page at issue. It was inappropriate to follow the subheading ‘Is there a role for enteric coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS) in

reducing GI complications’ with data referring only to CellCept. The Appeal Board considered that the claim ‘… it is not surprising that the enteric coat of MPS (EC-MPS) has no impact on GI complications’ was a strong unequivocal claim and that Roche had provided no data to support it. The page in question discussed both diarrhoea and GI

complications in general and moved seamlessly between the two thus introducing confusion into the mind of the reader about the relative incidence of diarrhoea as a discrete side effect and GI

complications as a whole. The Appeal Board noted that the page featured a provocative question followed by a series of selective bullet points. The language used was such that the cumulative effect was to place Myfortic in a disproportionately disadvanta ed position such that it was disparaged.

The Appeal Board thus upheld the Panel’s ruling of a breach of the Code.

Novartis stated that page 9 headed ‘Are you concerned about GI complications after transplantation?’, implied that it was rarely necessary to alter immunosuppression regimens in patients with GI complications after renal transplantation. Although it was true that dose reduction ‘might’ be unnecessary, it frequently was.

The final bullet point, ‘Most GI complications can be treated medically without the need to stop immunosuppression’, had no value in the context of transplantation, as stopping immunosuppression was not a practical option because of the almost inevitable consequence of graft rejection and loss.

Perhaps the comment was designed to leave the reader with the opinion that GI complications could be treated medically without the need to alter immunosuppression.

Novartis stated that the booklet systematically misled the reader about the relative importance of CellCept in the aetiology of GI complications after transplantation. By misrepresenting the adverse event profile of CellCept, and thereby falsifying its risk benefit profile, Roche was placing patient safety at risk. Roche’s consideration of Novartis’ comments in 2005, followed by the deliberate reprinting of a larger format item with the continued distortion of the risk benefit profile of CellCept suggested conscious intent.

The Panel considered that the summary page reinforced the impression that the only GI adverse event to be concerned about was diarrhoea. Dose reduction was mentioned but only in the context of being used unnecessarily. The Panel again noted the use of a heading which referred to GI complications as a whole and data which related only to diarrhoea. Overall the Panel considered that the booklet was about the management of diarrhoea post-transplant although many of the headings, claims and the title of the booklet itself, referred to GI complications as a whole. Given the context in which it appeared, ie in a book about the management of diarrhoea, the claim ‘Most GI 5 Code of Practice Review February 2007 complications can be treated medically without the need to stop immunnosuppression’ implied that diarrhoea in most CellCept patients was due to something other than CellCept. From the data before it the Panel considered that this was misleading. A breach of the Code was ruled.

Although noting its rulings above, the Panel did not consider that the booklet was prejudicial to patient safety and so in that regard it did not warrant a ruling of a breach of Clause 2 of the Code which was used as a sign of part.

CASE AUTH/1855/6/06 NOVARTIS v ROCHE CellCept booklet

Novartis complained about a CellCept (mycophenolate mofetil) booklet entitled ‘Are you concerned about GI [gastrointestinal] complications after transplantation?’ issued by Roche. CellCept was indicated in combination with ciclosporin and corticosteroids for the prophylaxis of acute transplant rejection in patients receiving allogenic, renal, cardiac or hepatic transplants. Novartis supplied Myfortic (enteric coated mycophenolate sodium) which was also used in combination with ciclosporin and corticosteroids but only for the prophylaxis of acute transplant rejection in adults receiving allogenic renal transplants. Novartis alleged the booklet misrepresented the role of immunosuppression, specifically CellCept, in the aetiology of GI complications following transplantation and was inconsistent with the CellCept summary of product characteristics (SPC). Page 1 was headed ‘GI complications in transplantation’. In a list of causes of GI adverse events infections was at the top and drug-induced effects, for example antibiotics and immunosuppressants, was at the bottom. Novartis believed this oversimplified the aetiology of GI adverse events to minimise the association with CellCept. In the context of a CellCept promotional piece, and in view of the prominence of GI side effects in the CellCept SPC, immunosuppression (if not specifically CellCept) should be listed first in any ranking of causes for GI side effects after transplantation; both because it was directly toxic to the GI tract and because it was a potent immunosuppressant that increased the risk of infections which might be associated with GI symptoms.

The Panel noted from the CellCept SPC that treatment should be initiated and maintained by appropriately qualified transplant specialists and that the principal adverse reactions associated with therapy included diarrhoea, leucopenia, sepsis and vomiting. The SPC also stated that all transplant patients were at increased risk of opportunistic infections; the risk increased with total immunosuppressive load. The most common infections in patients followed for at least one year were candida mucocutaneous, CMV viraemia/syndrome and Herpes simplex. With regard to GI adverse reactions, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and nausea were listed as very common (≥1/10) and GI haemorrhage, peritonitis, ileus, colitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastritis, oesophagitis, stomatitis, constipation, dyspepsia, flatulence and eructation were listed as common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10).

The Panel noted that on the page headed ‘GI complications in transplantation’, specific mention was made regarding GI adverse events with CellCept. The page stated that ‘The use of CellCept has led to significant reductions in graft rejection and improved long-term graft survival and function, but GI effects are still a concern with immunosupression’. Drug induced effects were included on the list of causes of GI adverse events. The list did not give any indication of the incidence or ranking of the importance of infection, surgery, concomitant diseases or drugs in causing GI complications. The Panel noted that Rubin (2001) stated that it was often very difficult to distinguish between infection-related and immunosuppression-related GI complications after transplantation. The causes might differ depending upon the time post-transplant and this time line was helpful in determining whether a GI complication was likely to be related to infection rather than a specific effect of an immunosuppressant medicine.

The Panel did not accept that the list oversimplified the aetiology of GI adverse events. The booklet was aimed at a specialised audience. No breach of the Code was ruled.

Page 2 was sub headed ‘Determining the probable cause can prove a prudent course of action’ and included two quotations: ‘Inappropriate dose reduction of an immunosuppressive agent that may not be the cause of the diarrhoea may result in an unnecessarily increased risk of acute rejection, the long-term impact of which is far more detrimental to patient or graft survival.’ (Pescovitz et al 2001) and ‘As infections very often have GI symptoms, it is important to rule out infection before looking to the immunosuppressive drug regimen as the cause of a patient’s GI problem.’ (Rubin 2001).

Novartis alleged that these quotations suggested that intervention to reduce GI side effects during Cellcept therapy should be delayed until GI symptoms had been investigated and implied that the true cause was frequently independent of the dose of immunosuppression given. These views were not consistent with the CellCept SPC. In addition, it was not made clear that the quotations represented opinions expressed in a journal supplement which had not been peer-reviewed rather than the evidence based conclusion of a study.

The Panel did not consider that the page was inconsistent with the CellCept SPC as alleged. The CellCept SPC listed GI adverse events as well as generally linking immunosuppression to infections. The specialist audience would be well aware of the difficulties with immunosuppression treatment. It was a matter for the specialists to decide whether to lower the dose of CellCept and when this should happen. The Panel did not accept that the page implied that the true cause of GI complications was frequently independent of the dose of immunosupressant used. In the Panel’s view the main message of the page was summed up in the sub-heading ‘Determining the probable cause can prove to be a prudent course of action’.

The Panel did not consider that the Code required promotional material to indicate that a quotation had been taken from a source that had not been peer-reviewed as alleged. The Code required quotations to be factual and accurate and not misleading. The source needed to be cited. The Panel ruled that on the evidence before it there was no breach of the Code.

Page 3 was sub headed ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’ and presented data from Maes et al (2003) on 26 renal transplant patients on an immunosuppressive regime which included CellCept. An infectious cause of diarrhoea was demonstrated in approximately 60% (n=13). A graph showed that of those thirteen patients 92% (n=12) had diarrhoea primarily treated with antimicrobial agents; in the remaining patient, with a concomitant malignant disorder, immunosuppressant therapy was stopped. The page concluded that ‘Diarrhoea was successfully treated with antimicrobial agents without the need for permanent reduction or cessation of immunosuppressant’.

Novartis alleged that the strong claim of the ‘proven’ benefit of excluding infection was not supported by the data presented. Half of the 26 patients with diarrhoea, selected as a subset of 765 patients, had an infectious cause of their diarrhoea. This was clearly not a ‘proven benefit’, particularly when one considered that CellCept itself predisposed to infection through immunosuppression. Furthermore, the use of a graph with an impressive 92% graphic created a misleading impression of robust support for the claim.

The data presented related specifically to persistent afebrile diarrhoea but the headings were ‘Managing GI adverse events’ and ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’. Diarrhoea was only one of the GI adverse events listed in the CellCept SPC and no evidence was supplied for the benefit of excluding infection in the remainder.

The Panel noted that the graph on the page headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ showed that 92% of patients had diarrhoea treated primarily with antimicrobial agents. A sub-heading read ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’. The Panel considered that at first glance the page seemed to suggest that in 92% of patients with GI adverse events, diarrhoea could be controlled with antimicrobials without the need to reduce the dose of immunosuppressant. This was not the case. The 92% related to the subset of patients with persistent afebrile diarrhoea in whom an infectious cause was found ie 13 patients. In the other patients in whom no infection was determined, immunosuppressive therapy was either reduced or stopped. Thus in an original group of 26 patients with afebrile diarrhoea, an infectious cause was demonstrated in 13, only 12 of whom were successfully treated with antibiotics ie <50% (12/26) as opposed to the 92% (12/13) depicted in the graph. The Panel considered that the page was misleading in this regard. The Panel also considered that it was misleading for a page headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ to focus only on data in patients with persistent afebrile diarrhoea.

The graph presented the data accurately but in the Panel’s view was not presented in such a way as to give a clear, fair, balanced view of the data. It was visually misleading. A breach of the Code was ruled. The Panel did not consider that the page failed to maintain a high standard.

Novartis alleged that pages 4 and 5, headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ and ‘Managing infectious diarrhoea’ contributed to the impression that infection was the most important cause of GI upset and that it was independent of immunosuppression (Cellcept). The treatment algorithm suggested that immunosuppression should only be considered a cause for GI upset once infection had been excluded.

The Panel did not agree with Novartis’ submission. The subheading implied that it was important to distinguish between infection-related and immunosuppression-related GI complications. In the Panel’s view the pages encouraged a pragmatic approach ie that the cause of diarrhoea should be established before any treatment changes were introduced. The Panel did not consider that the pages were misleading and thus ruled no breach of the Code.

Page 7 ‘Managing non-infectious diarrhoea’, referred to 10 patients of the 23 patients with afebrile diarrhoea that did not have an infectious cause and were presumed to have drug-induced diarrhoea (Maes et al). This was followed by ‘All immunosuppressant regimens are associated with diarrhoea to a greater or lesser extent’. The frequency of study-reported diarrhoea post transplantation was given in a table.

Novartis stated that in an attempt to create a perception that the licensed use of CellCept was no more associated with GI adverse events than other immunosuppressants, GI adverse event rates seen with a number of alternative regimens were presented under the heading ‘Frequency of study reported diarrhoea post transplantation’. However, the combination of tacrolimus and CellCept was not licensed and the use of ciclosporin and sirolimus in combination beyond three months (as per the reference cited) was specifically contraindicated in the sirolimus SPC, making this another unlicensed safety claim.

The Panel noted that the combination of CellCept and tacrolimus was not mentioned in the therapeutic indications, Section 4.1, of the CellCept SPC. Mention was made in Section 4.5 interactions. The Panel did not consider that in the context of the table it was unreasonable to include details of the frequency of diarrhoea with this combination. Ciclosporin and sirolimus were licensed for use for 3 months. The Panel did not consider in the context of the page at issue that the information about the frequency of diarrhoea with regard to CellCept and tacrolimus and ciclosporin and sirolimus were unlicensed safely claims as alleged. No breach of the Code was ruled although the Panel considered that the information could have been better presented to make the limitations clear.

Novartis alleged that page 8 of the booklet headed ‘Managing non-infectious diarrhoea’ and sub headed ‘Is there a role for enteric-coated mycopenolate sodium (EC-MPS) [Myfortic] in reducing GI complications?’, disparaged its product, Myfortic. It presented a hypothesis based on a single bioavailability study that compared oral and IV administration of CellCept (ie a study that did not contain Myfortic. The hypothesis, which relied on the faulty premise of a single potential mechanism (topical effect), was used to support the statement ‘As such, it is not surprising that the enteric coat of MPS has no impact on GI complications’. It ignored alternative potential mechanisms, such as pharmacokinetic differences between the products.

The statement ‘EC-MPS has no advantage on tolerability over CellCept and no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept’, was referenced to a letter of opinion, written by a single clinician and in French, and was not an evidence based conclusion. Data comparing the rate of diarrhoea with CellCept and Myfortic was taken from a study which excluded patients unable to tolerate CellCept and as such provided little insight into the relative tolerability of the two agents. The statement also ignored the fact that the exploration of potential GI differences between the products remained the subject of a study.

The Panel noted that Salvadori et al (2003) compared CellCept with Myfortic and concluded that the products were therapeutically equivalent with a comparable safety profile. Within 12 months 15% of Myfortic and 19.5% of CellCept patients required dose changes for GI adverse events (p=ns). The study was not designed to statistically detect differences between treatment groups in terms of GI tolerability. The claim that [Myfortic] had no impact on GI complications was a strong one. The Panel noted that although the claim ‘[Myfortic] has no advantage on tolerability over CellCept and no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept’ was referenced to a single author, it appeared to be a quotation in that paper from a larger body, it was thus not just the opinion of a single clinician. Novartis had not submitted data to support its complaint although a study was ongoing.

The comparison of rates of diarrhoea were from Budde et al (2003). The discussion noted that patients entered into the study were receiving and therefore tolerating [CellCept] at a dose of 2000mg which might introduce a bias. The Panel considered that the page had not put this data in context. It was inappropriate to follow the subheading ‘Is there a role for enteric coated mycophenolate sodium (ECMPS) in reducing GI complications’ with data referring only to CellCept.

The Panel noted that according to the SPCs for CellCept and Myfortic, diarrhoea was a very common side effect with both (≥ 10%). However the other very common GI side effects of CellCept (vomiting, abdominal pain and nausea) only occurred commonly (≥ 1% and <10%) with Myfortic. Similarly some of the commonly occurring GI disorders with CellCept (eructation, ileus, oesophagitis, gastrointestinal haemorrhage) were uncommon (≥ 0.1% and <1%) with Myfortic. Thus, although both products were associated with a number of similar GI disorders there seemed to be a lessening of effect with Myfortic.

The Panel again noted that subheadings referred to GI complications as a whole whereas some of the data presented referred specifically to diarrhoea. On balance the Panel considered that the page disparaged Myfortic and a breach of the Code was ruled. This ruling was appealed by Roche.

The Appeal Board was concerned about the content and layout of the page at issue. It was inappropriate to follow the subheading ‘Is there a role for enteric coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS) in reducing GI complications’ with data referring only to CellCept. The Appeal Board considered that the claim ‘… it is not surprising that the enteric coat of MPS (EC-MPS) has no impact on GI complications’ was a strong unequivocal claim and that Roche had provided no data to support it. The page in question discussed both diarrhoea and GI complications in general and moved seamlessly between the two thus introducing confusion into the mind of the reader about the relative incidence of diarrhoea as a discrete side effect and GI complications as a whole. The Appeal Board noted that the page featured a provocative question followed by a series of selective bullet points. The language used was such that the cumulative effect was to place Myfortic in a disproportionately disadvantaged position such that it was disparaged. The Appeal Board thus upheld the Panel’s ruling of a breach of the Code.

Novartis stated that page 9 headed ‘Are you concerned about GI complications after transplantation?’, implied that it was rarely necessary to alter immunosuppression regimens in patients with GI complications after renal transplantation. Although it was true that dose reduction ‘might’ be unnecessary, it frequently was. The final bullet point, ‘Most GI complications can be treated medically without the need to stop immunosuppression’, had no value in the context of transplantation, as stopping immunosuppression was not a practical option because of the almost inevitable consequence of graft rejection and loss. Perhaps the comment was designed to leave the reader with the opinion that GI complications could be treated medically without the need to alter immunosuppression.

Novartis stated that the booklet systematically misled the reader about the relative importance of CellCept in the aetiology of GI complications after transplantation. By misrepresenting the adverse event profile of CellCept, and thereby falsifying its risk benefit profile, Roche was placing patient safety at risk. Roche’s consideration of Novartis’ comments in 2005, followed by the deliberate reprinting of a larger format item with the continued distortion of the risk benefit profile of CellCept suggested conscious intent.

The Panel considered that the summary page reinforced the impression that the only GI adverse event to be concerned about was diarrhoea. Dose reduction was mentioned but only in the context of being used unnecessarily. The Panel again noted the use of a heading which referred to GI complications as a whole and data which related only to diarrhoea. Overall the Panel considered that the booklet was about the management of diarrhoea post-transplant although many of the headings, claims and the title of the booklet itself, referred to GI complications as a whole. Given the context in which it appeared, ie in a book about the management of diarrhoea, the claim ‘Most GI complications can be treated medically without the need to stop immunnosuppression’ implied that diarrhoea in most CellCept patients was due to something other than CellCept. From the data before it the Panel considered that this was misleading. A breach of the Code was ruled.

Although noting its rulings above, the Panel did not consider that the booklet was prejudicial to patient safety and so in that regard it did not warrant a ruling of a breach of Clause 2 of the Code which was used as a sign of particular censure and reserved for such use.

Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd complained about a CellCept (mycophenolate mofetil) booklet (ref P212582/1105) entitled ‘Are you concerned about GI [gastrointestinal] complications after transplantation?’ issued by Roche Products Limited for use by its hospital sales specialists with transplant specialists and health professionals. CellCept was indicated in combination with ciclosporin and corticosteroids for the prophylaxis of acute transplant rejection in patients receiving allogenic, renal, cardiac or hepatic transplants. Novartis supplied Myfortic (enteric coated mycophenolate sodium) which was also used in combination with ciclosporin and corticosteroids but only for the prophylaxis of acute transplant rejection in adults receiving allogenic renal transplants.

Novartis alleged the booklet breached Clauses 2, 7, 9 and 11 of the Code as it misrepresented the role of immunosuppression, specifically CellCept, in the aetiology of GI complications following transplantation and was inconsistent with the CellCept summary of product characteristics (SPC).

Novartis’ principal concern related to how the safety profile of CellCept was presented. The piece was designed in the style of an educational booklet on GI complications after transplant surgery, however its underlying intent was to distance CellCept from its well recognised association with GI complications. The overall impression was that infection, rather than immunosuppression, was the main cause of GI adverse events during CellCept therapy. In contrast, the CellCept SPC listed vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and nausea as being very common and GI haemorrhage, peritonitis, ileus, colitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastritis, oesophagitis, stomatitis, constipation, dyspepsia, flatulence and eructation as being common during therapy. The SPC also stated under ‘Special warnings and precautions for use’ that ‘oversuppression of the immune system increases the susceptibility to infection including opportunistic infections, fatal infections and sepsis’.

Roche rejected the allegation that it was attempting to mislead the transplant community as to the relationship between CellCept and GI adverse events. The booklet was not inconsistent with the SPC and it gave a fair, clinically relevant, and balanced review of the issues at hand. Roche wanted to encourage rational prescribing and to preserve graft viability, in accordance with the following rationale:

1 The safety of the patient and their graft was paramount.

2 Diarrhoea was a significant concern when managing transplant recipients, and might be related to immunosuppression.

3 There were other causes of diarrhoea that should be considered (and treated where appropriate) before reducing or altering immunosuppression.

4 Reducing or altering immunosuppression had been shown to increase the risk of acute rejection episodes, and graft loss at 3 years graft (Knoll et al, 2003; Pelletier et al, 2003).

The booklet at issue was withdrawn in April 2006.

1 Page 1: ‘GI complications in transplantation’

COMPLAINT

A list of causes of GI adverse events was given, with infections at the top and finishing with drug-induced effects, for example antibiotics and immunosuppressants, at the bottom. Novartis believed this oversimplified the aetiology of GI adverse events in order to minimise the association with CellCept. In intercompany correspondence, Roche had previously suggested that the position of immunosuppression at the bottom of the list was ‘visually prominent’; however Novartis believed that this was inconsistent with accepted conventions of hierarchy in the presentation of information. In the context of a CellCept branded promotional piece, and in view of the prominence of GI side effects in the CellCept SPC, immunosuppression (if not specifically CellCept) should occupy first position in any ranking of causes for GI side effects after transplantation; both because it was directly toxic to the GI tract and because it was a potent immunosuppressant that increased the risk of infections which might be associated with GI symptoms. Breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.8, 7.9 and 7.10 were alleged.

RESPONSE

Roche stated that, as there were no figures for incidences presented for any of the potential causes given or numbering of points, it disagreed that this list imparted any special sense of hierarchy. For instance, a list of particulars such as age, sex, date of birth, was similarly without hierarchy.

On the contrary, the positioning of ‘immunosuppressants’ at the end of the list was visually quite impactful. Furthermore, the paragraph preceding the list stated ‘The use of CellCept has led to significant reductions in graft rejection and improved long-term graft survival and function, but GI effects are still a concern with immunosuppression’. Therefore, Roche believed it had appropriately highlighted the association of immunosuppression, and CellCept, with GI adverse events.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted from the CellCept SPC that treatment should be initiated and maintained by appropriately qualified transplant specialists; it would thus be prescribed by individuals with a great deal of knowledge in the therapy area. The undesirable effects section of the CellCept SPC stated that the principal adverse reactions associated with the administration of CellCept in combination with ciclosporin and corticosteroids included diarrhoea, leucopenia, sepsis and vomiting and there was evidence of a higher frequency of certain types of infection. Under a sub-heading of ‘Opportunistic infections’, the SPC also stated that all transplant patients were at increased risk of opportunistic infections; the risk increased with total immunosuppressive load. The most common infections in patients followed for at least one year were candida mucocutaneous, CMV viraemia/syndrome and herpes simplex. With regard to GI adverse reactions, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea and nausea were listed as very common (≥1/10) and GI haemorrhage, peritonitis, ileus, colitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastritis, oesophagitis, stomatitis, constipation, dyspepsia, flatulence and eructation were listed as common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10).

The Panel noted that the page was headed ‘GI complications in transplantation’. No specific mention was made regarding GI adverse events with CellCept. The page stated that ‘The use of CellCept has led to significant reductions in graft rejection and improved long-term graft survival and function, but GI effects are still a concern with immunosupression’. Drug-induced effects were included on the list of causes of GI adverse events. The list did not give any indication of the incidence or ranking of the importance of infection, surgery, concomitant diseases or drugs in causing GI complications. The Panel noted that Rubin (2001) stated that it was often very difficult to distinguish between infection-related and immunosuppression-related GI complications after transplantation. The causes might differ depending upon the amount of time post-transplant and this time line was helpful in determining whether a GI complication was likely to be related to infection rather than a specific effect of an immunosuppressant medicine.

The Panel did not accept that the list oversimplified the aetiology of GI adverse events. The booklet was aimed at a specialised audience. Thus the Panel ruled no breach of Clauses 7.2, 7.8, 7.9 and 7.10 of the Code.

2 Page 2: ‘GI complications in transplantation’

Page 2 was sub headed ‘Determining the probable cause can prove a prudent course of action’ and included two quotations:

‘Inappropriate dose reduction of an immunosuppressive agent that may not be the cause of the diarrhoea may result in an unnecessarily increased risk of acute rejection, the long-term impact of which is far more detrimental to patient or graft survival.’ (Pescovitz et al 2001) and ‘As infections very often have GI symptoms, it is important to rule out infection before looking to the immunosuppressive drug regimen as the cause of a patient’s GI problem.’ (Rubin 2001).

COMPLAINT

Novartis alleged that the two quotations from a 2001 journal supplement suggested that intervention to reduce GI side effects during Cellcept therapy should be delayed until GI symptoms had been investigated and created the impression that the true cause was frequently independent of the dose of immunosuppression given. As detailed above, these views were not consistent with the CellCept SPC. In addition, it was not made clear that the quotations represented opinions expressed in a journal supplement which had not been peer-reviewed rather than the evidence based conclusion of a study. Breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.4, 7.6, 7.10, 11.4 were alleged.

RESPONSE

Roche noted that none of the statements in the SPC stated that CellCept alone caused GI complications. The SPC provided no detail as to the actual underlying cause of the GI events for example whether they resulted from a direct effect of CellCept and/or its use in combination immunosuppression, or indirectly due to opportunistic infection arising from over immunosuppression with CellCept in combination with other immunosuppressants. Furthermore, there was no recommendation for dose reduction of CellCept in terms of managing either GI adverse events or infections. Therefore Roche did not believe that the statements were inconsistent with the CellCept SPC.

The quotations came from review articles contained in a supplement to a peer-reviewed journal, Clinical Transplantation. These comments represented current medical thinking, as demonstrated by a quotation from a recent peer-reviewed publication of a prospective study examining the relationship between immunosuppression and diarrhoea:

‘As changes to immunosuppressive therapy can be the result of perceived drug-related adverse effects, and as such changes are associated with an increased risk of acute rejection, it seems imperative that the cause of GI complications in patients receiving immunosuppressant therapy should be fully investigated.’ (Maes et al, 2006).

PANEL RULING

The Panel did not consider that the page was inconsistent with the CellCept SPC as alleged. The CellCept SPC listed GI adverse events as well as generally linking immunosuppression to infections. The specialist audience would be well aware of the difficulties with immunosuppression treatment. It was a matter for the specialists to decide whether to lower the dose of CellCept and when this should happen. The Panel did not accept that the page gave the impression that the true cause of GI complications was frequently independent of the dose of immunosupressant used. In the Panel’s view the main message of the page was summed up in the subheading ‘Determining the probable cause can prove to be a prudent course of action’.

The Panel did not consider that the Code required promotional material to indicate that a quotation had been taken from a source that had not been peerreviewed as alleged. The Code required quotations to be factual and accurate and not misleading. The source needed to be cited.

The Panel considered that on the evidence before it there was no breach of Clauses 7.2, 7.4, 7.6, 7.10 and 11.4 of the Code.

3 Page 3: ‘Managing GI adverse events’

Page 3 was sub headed ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’ and presented data from Maes et al (2003) on 26 renal transplant patients on an immunosuppressive regime which included CellCept. An infectious cause of diarrhoea was demonstrated in approximately 60% (n=13). A graph was included which showed that of those thirteen patients 92% (n=12) had diarrhoea primarily treated with antimicrobial agents; in the remaining patient, with a concomitant malignant disorder, immunosuppressant therapy was stopped. The page concluded that ‘Diarrhoea was successfully treated with antimicrobial agents without the need for permanent reduction or cessation of immunosuppressant’.

COMPLAINT

Novartis alleged that the strong claim of the ‘proven’ benefit of excluding infection was not supported by the data presented. Half of the 26 patients with diarrhoea, selected as a subset of 765 patients, had an infectious cause of their diarrhoea. This was clearly not a ‘proven benefit’, particularly when one considered that CellCept itself predisposed to infection through immunosuppression. Furthermore, the use of a graph with an impressive 92% graphic created a misleading impression of robust support for the claim.

The data presented related specifically to persistent afebrile diarrhoea but the headings were ‘Managing GI adverse events’ and ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’. Diarrhoea was only one of the GI adverse events listed in the CellCept SPC and no evidence was supplied for the benefit of excluding infection in the remainder; vomiting, abdominal pain, nausea, GI haemorrhage, peritonitis, ileus, colitis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastritis, oesophagitis, stomatitis, constipation, dyspepsia, flatulence and eructation. Breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.4, 7.8, 7.10, 9.1 were alleged.

RESPONSE

Roche stated it was difficult to understand the thinking behind Novartis’ concern. Anyone involved in transplantation would know that excluding infection should be a major safety consideration to avoid inappropriate reduction of immunosuppression, increasing the risk of rejection and graft loss. Maes et al had proven the benefit of examining nonimmunosuppressant causes of diarrhoea, whereby management of symptoms did not always require reduction of immunosuppression. The study showed that a proportion of patients had resolution of their diarrhoea when infectious causes were investigated and treated accordingly. This was achieved without major change to the patient’s immunosuppression, and was therefore more beneficial in terms of the patient and the healthcare system.

The title of this page was but one page examining GI adverse events in this item. Clearly, the main GI adverse event of concern was diarrhoea, due to the negative impact of dehydration on graft function.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted that the page headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ featured a graph showing that 92% of patients had diarrhoea treated primarily with antimicrobial agents. The sub-heading to the page read ‘The proven benefit of excluding infection’. The Panel considered that at first glance the page seemed to suggest that in 92% of patients with GI adverse events, diarrhoea could be controlled with antimicrobials without the need to reduce the dose of immunosuppressant. This was not the case. The 92% related to the subset of patients with persistent afebrile diarrhoea in whom an infectious cause was found ie 13 patients. In the other patients in whom no infection was determined, immunosuppressive therapy was either reduced or stopped. Thus in an original group of 26 patients with afebrile diarrhoea, an infectious cause was demonstrated in 13, only 12 of whom were successfully treated with antibiotics ie <50% (12/26) as opposed to the 92% (12/13) depicted in the graph. The Panel considered that the page was misleading in this regard. The Panel also considered that it was misleading for a page headed ‘Managing GI adverse events’ to focus only on data in patients with persistent afebrile diarrhoea. The heading related to all GI adverse events but the data shown related to only one specific effect. Breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.4 and 7.10 were ruled.

The graph presented the data accurately but in the Panel’s view was not presented in such a way as to give a clear, fair, balanced view of the data. It was visually misleading. A breach of Clause 7.8 of the Code was ruled.

The Panel did not consider that the page failed to maintain a high standard and thus no breach of Clause 9.1 of the Code was ruled.

4 Pages 4 and 5: ‘Managing GI adverse events’ and ‘Managing infectious diarrhoea’

COMPLAINT

Novartis stated that these pages contributed to the impression that infection was the most important cause of GI upset and that it was independent of immunosuppression (Cellcept). The treatment algorithm suggested that immunosuppression should only be considered a cause for GI upset once infection had been excluded. It was interesting to note that the first version of this booklet included a similar flow chart and referenced Behrend (2001). Novartis pointed out to Roche that Behrend advocated an entirely different, and more widely accepted, approach of careful review of medication, particularly immunosuppressant, with a view to reducing or splitting the dose of CellCept early in the management of GI adverse events. The current version of the algorithm clearly took these comments into account as Behrend was no longer cited, but the content remained similarly unbalanced. Breaches of Clauses 7.2, 7.4, 9.1 were alleged.

RESPONSE

Roche rejected the assertion by Novartis that these two pages implied that infection was the most important cause of GI adverse effects, and that it was independent of immunosuppression (CellCept). There were no statements on either page that supported this complaint.

Roche intended the two pages to present distinguishing features of infection versus immunosuppression-related GI adverse events, and a proposal for a suggested approach for managing infection-related diarrhoea. This was in line with the main aim of the item, whereby other causes of diarrhoea should be considered before reducing or altering immunosuppression and putting the graft at risk. Should infection as a cause be excluded, page 6 went on to provide suggestions for managing noninfectious/drug-induced diarrhoea, including reduction of immunosuppressive therapy.

Roche had taken previous comments made by Novartis and reviewed the referencing to avoid inconsistencies with the CellCept SPC, which did not recommend dose reduction for GI adverse events.

PANEL RULING

The Panel did not consider that pages 4 and 5 implied that infection was the most important cause of GI upset and that this was independent of the immunosupression. The subheading implied that it was important to distinguish between infectionrelated and immunosuppression-related GI complications. In the Panel’s view the pages encouraged a pragmatic approach ie that the cause of diarrhoea should be established before any treatment changes were introduced. The Panel did not consider that the pages were misleading and thus ruled no breach of Clauses 7.2, 7.4 and 9.1 of the Code.

5 Page 7: ‘Managing non-infectious diarrhoea’

The page referred to 10 patients of the 23 patients with afebrile diarrhoea that did not have an infectious cause and were presumed to have drug-induced diarrhoea (Maes et al). This was followed by ‘All immunosuppressant regimens are associated with diarrhoea to a greater or lesser extent’.

The frequency of study-reported diarrhoea post transplantation was given in a table.

COMPLAINT

Novartis stated that in an attempt to create a perception that the licensed use of CellCept was no more associated with GI adverse events than other immunosuppressants, GI adverse event rates seen with a number of alternative regimens were presented under the heading ‘Frequency of study-reported diarrhoea post transplantation’.

The combination of tacrolimus and CellCept was not licensed. The regimen of ciclosporin and sirolimus was licensed; however the continuation of the combination beyond three months (as per the reference cited) was specifically contraindicated in the sirolimus SPC, making this another unlicensed safety claim. A breach of Clause 7.10 was alleged.

RESPONSE

Roche stated that this table was presented under the statement ‘All immunosuppressant regimens are associated with diarrhoea to a greater or lesser extent’, and reported the incidence of diarrhoea from randomised, controlled trials of different immunosuppressant combinations in de novo transplant recipients (as this was the population most likely to experience GI problems).

For the ciclosporin and sirolimus combination, the frequency of diarrhoea reported in both the sirolimus SPC and the pivotal studies cited were for the combination with ciclosporin and steroids.

Furthermore, the combination of CellCept and tacrolimus was reviewed in the CellCept SPC (section 4.2), which described a pharmacokinetic interaction resulting in increased exposure to mycophenolic acid in both renal and liver transplant recipients, an outcome of which might be increased side effects. As such, Roche did not believe it was inconsistent with the SPC to quote the incidence of diarrhoea for this combination. The presentation of information not cited in the licensed indication but related to other parts of the SPC, had previously been ruled as not inconsistent with SPC, and therefore allowable within the Code (Case AUTH/1100/11/00). No claim was being made about the efficacy of the combination of CellCept and tacrolimus, only useful safety data in accordance with the SPC. In addition, the combination of tacrolimus and CellCept in cardiac transplantation had recently been added to the tacrolimus SPC.

Roche believed that the nature and context in which the information presented in this table complied with the requirements of the Code.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted that the combination of CellCept and tacrolimus was not mentioned in the therapeutic indications, Section 4.1, of the CellCept SPC. Mention was made in Section 4.5 interactions. The Panel did not consider that in the context of the table it was unreasonable to include details of the frequency of diarrhoea with this combination. Ciclosporin and sirolimus were licensed for use for 3 months. The Panel did not consider that in the context of the page at issue the information about the frequency of diarrhoea with regard to CellCept and tacrolimus and ciclosporin and sirolimus were unlicensed safely claims as alleged. No breach of Clause 7.10 of the Code was ruled.

The Panel considered that the information could have been better presented to make the limitations clear.

6 Page 8: ‘Managing non-infectious diarrhoea’

Page 8 of the booklet was headed ‘Managing noninfectious diarrhoea’ and sub headed ‘Is there a role for enteric-coated mycopenolate sodium (EC-MPS) [Myfortic] in reducing GI complications?’ followed by:

- ‘The safety and tolerability of IV CellCept was assessed in a double-blind comparison with oral CellCept. GI adverse events such as vomiting and diarrhoea previously seen with the oral formulation, were not avoided with the IV formulation of CellCept.

- This supports the hypothesis that diarrhoea is not simply a topical effect of CellCept

- Moreover, gastro-resistant dosage forms claim to protect to mucosa of the stomach only, not that of the intestine

As such, it is not surprising that the enteric coat to MPS (EC-MPS) has no impact on GI complications:

- EC-MPS causes similar levels of GI adverse events to CellCept [Salvadori et al 2003]

- In a study comparing the two treatments, the rate of diarrhoea at three months were 4.9% (CellCept) and 5.0% (EC-MPS)

- EC-MPS has no advantage on tolerability over CellCept and no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept.’

COMPLAINT

Novartis alleged that this page disparaged its product, Myfortic. It presented a hypothesis based on a single bioavailability study that compared oral and IV administration of CellCept (ie a study that did not contain the product being denigrated). The hypothesis, which relied on the faulty premise of a single potential mechanism (topical effect), was used to support the statement ‘As such, it is not surprising that the enteric coat of MPS has no impact on GI complications’. It ignored alternative potential mechanisms, such as pharmacokinetic differences between the products.

The rather definitive statement ‘EC-MPS has no advantage on tolerability over CellCept and no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept’, was referenced to a letter of opinion, written by a single clinician and in French, and was not an evidence based conclusion. Data comparing the rate of diarrhoea with CellCept and Myfortic was taken from a study which excluded patients unable to tolerate CellCept and as such provided little insight into the relative tolerability of the two agents. The statement also ignored that fact that the exploration of potential GI differences between the products remained the subject of a study involving more than half of the renal transplant centres in the UK. This careful and unbalanced selection of data disparaged Myfortic in breach of Clause 8.1.

RESPONSE

Roche disagreed with Novartis that the information presented regarding EC-MPS and GI adverse events was disparaging. The statements reflected outcomes from randomized, controlled registration studies, which showed that EC-MPS provided no clinical benefit over CellCept in terms of GI adverse events. Including unproven theory and conjecture (as Novartis had cited), without any supporting clinical benefit of enteric-coating, was irrelevant.

PANEL RULING

The Panel noted that Salvadori et al (2003) compared CellCept (1000mg bid) with Myfortic (720mg bid) and concluded that the products were therapeutically equivalent with a comparable safety profile. Within 12 months 15% of Myfortic and 19.5% of CellCept patients required dose changes for GI adverse events (p=ns). The study was not designed to statistically detect differences between treatment groups in terms of GI tolerability. The claim that [Myfortic] had no impact on GI complications was a strong one. The Panel noted that although the claim ‘[Myfortic] has no advantage on tolerability over CellCept and no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept’ was referenced to Marquet (2004), it appeared to be a quotation in that paper from the Transparency Commission decision concerning Myfortic, French Republic 2004. ‘However it should be noted that according to current knowledge, Myfortic has no advantage in tolerability over CellCept and has no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept.’ This was more than the opinion of a single clinician. Novartis had not submitted data to support its complaint although a study was ongoing.

The comparison of rates of diarrhoea were from Budde et al (2003). The discussion noted that patients entered into the study were receiving and therefore tolerating [CellCept] at a dose of 2000mg which might introduce a bias as this population might not be representative of the overall transplant population. The Panel considered that the page had not put this data in context. It was inappropriate to follow the subheading ‘Is there a role for enteric coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS) in reducing GI complications’ with data referring only to CellCept.

The Panel noted that according to the SPCs for CellCept and Myfortic, diarrhoea was a very common side effect with both (≥ 10%). However the other very common GI side effects of CellCept (vomiting, abdominal pain and nausea) only occurred commonly (≥ 1% and <10%) with Myfortic. Similarly some of the commonly occurring GI disorders with CellCept

(eructation, ileus, oesophagitis, gastrointestinal haemorrhage) were uncommon (≥ 0.1% and <1%) with Myfortic. Thus, although both products were associated with a number of similar GI disorders there seemed to be a lessening of effect with Myfortic.

The Panel again noted that subheadings referred to GI complications as a whole whereas some of the data presented referred specifically to diarrhoea.

On balance the Panel considered that the page disparaged Myfortic and a breach of Clause 8.1 of the Code was ruled. This ruling was appealed.

APPEAL BY ROCHE

Roche submitted that the point of this page was not to disparage Myfortic, but to illustrate that no evidence existed to show any additional benefit of Myfortic or any enteric-coated formulations of mycophenolic acid (MPA – the shared active moiety) over CellCept in terms of diarrhoea, the major GI problem for transplant recipients.

Roche explained that the intention of the section subheaded ‘Is there a role for enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (EC-MPS) in reducing GI complications?’ was to highlight the available clinical evidence that suggested MPA-related diarrhoea was not simply the result of a topical effect, but was largely due to systemic exposure of MPA and/or its metabolites. Thus, an enteric-coated formulation of MPA was not likely to significantly reduce diarrhoea. This hypothesis was supported originally by the finding that rates of diarrhoea and vomiting were not reduced in the comparison of intravenous vs oral mycophenolate mofetil (Pescovitz et al, 2001). Whilst the Panel stated that it was inappropriate to follow the sub-heading with data referring only to CellCept, unfortunately there was no equivalent data for Myfortic (ie oral vs systemic administration) available. Furthermore, it was not possible to present the case for Myfortic reducing any GI complications (including diarrhoea), since none existed even though the molecule was developed with the hope of reducing GI adverse events. Therefore, Roche submitted that the sub-heading was fair and balanced on the basis of available data.

Roche noted the sub-heading ‘As such, it is not surprising that the enteric coat of MPS (EC-MPS) has no impact on GI complications’. Roche submitted that the claim of ‘no impact’ or additional benefit of Myfortic was based on the fact that there was no published, randomised, controlled trial (RCT) comparing Myfortic and CellCept that had demonstrated a statistically significant benefit for any GI outcome. This fact was reflected in the findings of the French Republic’s Transparency Commission decision concerning Myfortic (referenced on the same page of the booklet) (Marquet), which stated: ‘However it should be noted that according to current knowledge, Myfortic has no advantage in tolerability over CellCept and has no proven role in patients failing to tolerate CellCept’.

Roche acknowledged and accepted the Panel’s points regarding the use of the two Novartis pivotal studies (Salvadori et al, and Budde et al, 2003), which could have been presented more clearly. However, as the intention was to present the only robust data available on the comparison of GI adverse events (and specifically diarrhoea) from RCTs, the omission to qualify the limitations of the Novartis data did not constitute disparagement.

The only new data from a randomised, controlled study to become available since the preparation of this booklet was a comparison of Myfortic and CellCept in cardiac transplantation (Kobashigawa et al, 2006). Whilst this study had a number of limitations (ie single-blind, no blinding of formulations), and was not powered for safety outcomes, the GI adverse event profiles were provided.

Kobashigawa et al, Salvadori et al and Budde et al, showed no clear trend favouring either CellCept or Myfortic in terms of GI adverse events. With regards to the claims made on page 8 of the booklet, Roche submitted that it had not implied that Myfortic was worse than CellCept but showed that Myfortic offered no GI advantage.

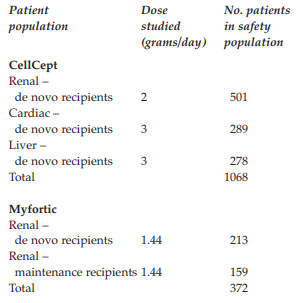

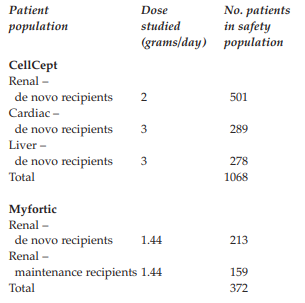

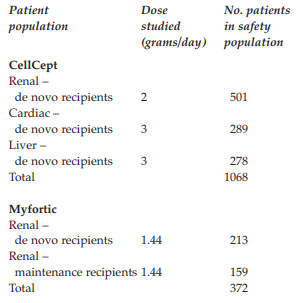

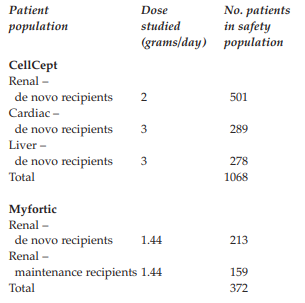

As there was no prospective, randomised clinical trial evidence to support a benefit of Myfortic over CellCept, it appeared that the Panel had based the ruling of disparagement on a comparison of the SPCs for Myfortic and CellCept stating: ‘Thus, although both products were associated with a number of similar GI disorders, there seemed to be a lessening of effect with Myfortic’. However, such a comparison was inappropriate as there were substantial differences in the populations represented, and attendant clinical conditions. The table below compared the pivotal studies from which the adverse events were reported for CellCept and Myfortic.

As there were differences in the number and populations of transplant recipients (both organ type and timing of introduction of therapy), as well as the doses studied, it was invalid to make direct comparisons of the GI adverse event profiles listed in the CellCept and Myfortic SPCs. Furthermore, in its comparison the Panel made an assumption about the impact of Myfortic on GI disorders without prospective RCT evidence to support it.

In summary, Roche submitted that the claims were fair, balanced and based on the available evidence base. The absence of robust data to support Myfortic’s position should not be construed as disparagement.

COMMENTS FROM NOVARTIS

Novartis submitted that the mechanism of MPA induced GI side effects and the selection of appropriate interventions for individual patients were topics of considerable research and debate. Despite this, Roche sought to justify definitive statements that disparaged the enteric coated nature of Myfortic (ECMPS) and made absolute statements about the effect of Myfortic on GI complications. For example:

‘EC-MPS has no impact on GI complications’

‘EC-MPS has no advantage on tolerability over Cellcept’ and ‘no proven role in patients failing to tolerate Cellcept’.

Novartis alleged that the page in question created the perception that the enteric coat of Myfortic had no role in reducing GI side effects. This perception was not substantiable and disparaged Myfortic.

After creating the impression of a theoretical basis for a lack of benefit to Myfortic’s enteric coat, the page went on to claim that this had been clinically proven by use of the statement, ‘As such it is not surprising that the enteric coat of MPS (EC-MPS) has no impact on GI complications’. Again this conclusion was substantiable and disparaged Myfortic.

The comparative GI tolerability of Myfortic and Cellcept remained the subject of debate and research. The majority of renal transplant centres in the UK were recruiting patients into a randomised study to compare the GI tolerability of the two. Had the question been resolved with the certitude proposed by Roche, Novartis would not have embarked on such a study nor would it have obtained independent Ethics Committee approval for its conduct.

Clearly a complex scientific question remained to be definitively answered through further research; pharmaceutical companies should not attempt to resolve it in the minds of prescribers by disparaging competitor products.

Novartis noted the claims ‘The safety and tolerability of IV Cellcept was assessed in a double-blind comparison with oral Cellcept. GI adverse events such as vomiting and diarrhoea previously seen with the oral formulation, were not avoided with the IV formulation of Cellcept’ (Pescovitz et al) and ‘This supports the hypothesis that diarrhoea is not simply a topical effect of Cellcept’ (Pescovitz et al). Novartis submitted that Pescovitz et al was not of sufficient quality to make comparative assessments of the tolerability of oral vs IV Cellcept. This study was presented as a double-blind comparison of oral and IV Cellcept yet both arms were given open label oral Cellcept for the majority of the study. The MPA exposures of the IV and oral formulations were not bioequivalent. The only period of direct comparison was the first 5 days after transplantation, when patients were recovering from major abdominal surgery, were frequently nil by mouth and were receiving antibiotics and opioid analgesia. This was clearly not representative of the potentially lifelong, chronic nature of MPA therapy after transplantation.

Pescovitz et al pertained to Cellcept but was presented under a subheading relating to EC-MPS. This was considered inappropriate by the Panel. In its appeal, Roche had tried to justify the extrapolation of Cellcept data to Myfortic by referring to the absence of equivalent data for Myfortic. It was hard to see how such data could ever be meaningfully generated when one considered the enteric coated nature of Myfortic.

The question of whether MPA toxicity was topical or systemic had not been resolved in favour of either mechanism. Current consensus favoured a complex, mixed aetiology but neither mechanism would preclude a role for an enteric coat in reducing GI side effects of MPA. Evidence to suggest a systemic cause did not mean that a local irritant effect of high local concentrations in the gut wall could be excluded. Even Pescovitz et al was cautious not to oversimplify the hypothesis: ‘perhaps agents that do not dissolve in the stomach may have less local toxicity, such as nausea or dyspepsia. The implication of the concentration controlled trial data was that if you can spread the dose of MMF, for example, over the day, you can reduce some of the local toxicity, but that this is more likely to avoid proximal GI symptomatology than distal’.

In Hale et al (1998), GI toxicity was more closely correlated with the oral dose of MMF given than with systemic exposure achieved. The authors stated, ‘It is possible that the risk of diarrhoea better relates to dose than a pharmacokinetic variable because the mechanistic basis of the event may be a local one acting within the gastrointestinal tract’.

An enteric coat might alter the tolerability profile of a medicine by altering pharmacokinetic variables. It was entirely reasonable that the enteric coat, by modifying parameters such as Cmax in individual patients prone to GI side effects of the Cellcept formulation, might have a role in reducing GI complications.

Mourad et al (2001) had demonstrated that, at a fixed dose of 2g/day, a high MPA concentration at 30 minutes was associated with an increased risk of side effects.

A common strategy to limit GI complications with Cellcept was to split the dosing from twice daily to three (or four) times daily or to dose Cellcept with food (Behrend 2001). Both of these interventions effectively reduced the Cmax.

As stated in the SPC and by Roche at the base of the page in question, the pharmacokinetic profile of Myfortic differed from that of Cellcept. This provided a theoretical mechanism for a difference in GI tolerability secondary to an enteric coat.

Novartis considered that the claim ‘Moreover, gastroresistant dosage forms claim to protect the mucosa of the stomach only, not that of the intestine’ appeared to assert that avoidance of topical toxicity in the stomach had no role in reducing GI complications. This was misleading because it ignored the existence of upper GI adverse events such as nausea, reflux, vomiting and gastritis.

Novartis noted the claims: ‘As such, it is not surprising that the enteric coat of MPS (EC-MPS) has no impact on GI complications’, ‘EC-MPS causes similar levels of GI adverse events to Cellcept’ (Salvadori et al) and ‘In a study comparing the two treatments, the rates of diarrhoea at three months were 4.9% (Cellcept) and 5% (EC-MPS)’ (Budde et al).

The two Myfortic Phase III registration studies referred to by Roche did not support the absolute conclusions drawn regarding comparative GI tolerability.

Salvadori et al was designed to demonstrate the therapeutic equivalence of EC-MPS and MMF and to compare their safety profiles. In the authors’ words, ‘It was not designed to statistically detect differences between treatment groups in terms of GI tolerability’.

Budde et al required patients to tolerate full dose Cellcept for 4 weeks prior to inclusion in the study, effectively excluding any patients who could not tolerate Cellcept from participation in the trial. This provided little true insight into the GI tolerability of either product, as evidenced by the extraordinarily low rates of diarrhoea in the study which were quoted by Roche.

Novartis considered that Roche’s statement, that it did not believe the omission to qualify the limitations of the Novartis data constituted disparagement, was revealing. Where the limitations of data prevented the generation of accurate or definite conclusions, the data should not be used to support unqualified and absolute statements in promotional material. This principle was not altered by the source of the data.

Novartis noted that Roche referred to Kobashigawa et al and presented a table which listed GI adverse event rates. However, Roche had failed to state that patients receiving EC-MPS had fewer dose reductions than MMF patients, which ‘might suggest better tolerability of EC-MPS’ (authors’ quote). The average daily dose (in percent of the nominal dose) was significantly lower in the MMF group (79% vs 88.4%, p = 0.015). Despite higher doses of MPA, patients on EC-MPS had numerically lower rates of diarrhoea (12.8% vs 22.4%, p=0.119). The number of patients in this study was acknowledged to be ‘relatively small and might not have been adequate to detect differences in specific side effects’.

Trial design was an important consideration in assessing the GI complications of drug therapy. Particular consideration must be given to the method of collection of GI adverse events.